Navigating with an Old Salt

A boat charter and a lesson in seamanship

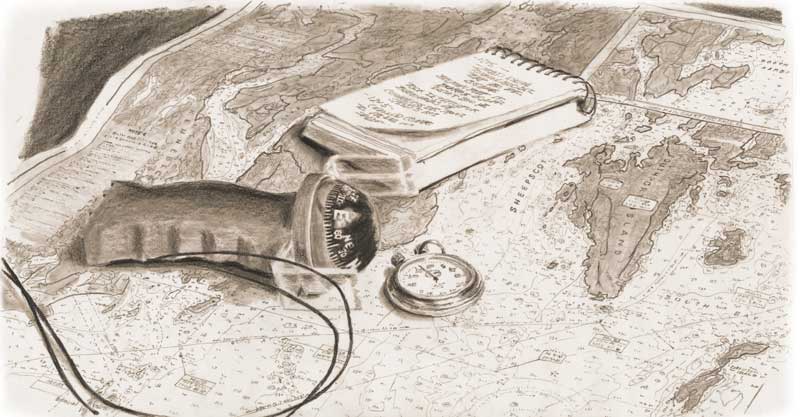

Illustration by Ted Walsh

Illustration by Ted Walsh

In the annals of colorful sailors, Lou Holladay ranks right up there with the saltiest of them. During his long life, years before I met him, he had been an ocean sailor, chemical engineer, yacht-design consultant, expert bridge player, competitive tennis player, and when I met him, he ran a small charter outfit.

I was in West Boothbay with my son to rent a sloop from Holladay for a week. We found Lou’s comfortable little clapboard house perched on a hill above the water near Southport Island. Minutes after I knocked on the screen door, Lou walked out into the bright afternoon sunlight. He was in his 80s but looked much younger. Tall and fit, he had a full head of blazing white hair, and thick, bushy eyebrows that were as white as cumulus clouds. He wore khaki trousers, a faded blue work shirt, and beat-up canvas tennis shoes.

“Hello”, I said with a smile. “I’m Larry and this is my son. We’ve chartered your Tartan 34 for the week.” I stuck out my hand expecting a warm handshake in return.

“You have, have you? Come inside and we’ll see.” I glanced at my son quizzically, and we followed Lou into the house. He sat down at an ancient rolltop desk that was piled high with papers, bills, magazines, and correspondence. “Ah, here it is.” He held up the letter I had written after seeing his ad in the back of a boat magazine. “Yes. All right. You two get your things together and stow them on the boat. I’ll see you tomorrow morning at 8.”

We were ready bright and early the next morning. The Tartan sloop was a little old, but solid. Lou had not equipped it with any new gadgets or fancy equipment. It had an Atomic 4 gasoline engine, compass, mainsail, and a working jib with no roller furling. The only electronic aid was a basic VHF radio. As I looked at the hull from the dinghy, I realized that the boat was painted with the same paint I had seen on the sides of the boat shed behind Lou’s house. “Well, nothing wrong with being frugal,” I thought.

Lou pulled alongside, stood up in the dink, stretched one long leg up and onto the gunwale, grabbed the lifeline, and in a flash hoisted himself on deck in one smooth, fluid motion. He took me around the boat and showed me the engine controls. He had me pull the jib out of the sailbag and hank it on.

Next, he stood in the companionway and issued orders. I took the helm, my son dropped the mooring, and we proceeded out, past the swing bridge. When we got to the wide bay, he pulled out a chart, pointed to features, and rapidly quizzed me.

“What are these numbers?”

“The depth of the water.”

“These?”

“A red nun and a green can. Coming into port it’s red, right, returning.”

“And what’s this thing?” he asked.

“That’s a lighted bell buoy.”

“And this?”

“It’s a lighthouse,” I answered.

Then he asked, “If you’re coming in at night, or in a pea soup thick fog, how do you know which one it is?”

“Well, you…uh, you just well….”

He reached down and pulled out a thick yellow book that was hanging on a string. “You see this? This is Eldridge. It has everything you ever need to know.” He flipped it open to the page with our buoy and lighthouse, and showed me how the book described the characteristics of each aid to navigation. Whether its signal is a light, a horn, or a whistle. Its height, its range, duration, frequency. Its location in latitude and longitude.

I realized that my navigation skills were woefully inadequate. It was a humbling experience. He spread the chart out on the cockpit seat and pointed out over the bow to a low-lying shape off in the distance. It was shrouded in haze and I could barely make it out. “What’s that?” he asked. I looked down at the chart and back up at the mass in the distance. “Damariscove Island,” I said confidently. “Look again,” he replied. I squinted my eyes. “Umm, Outer Heron. No, The Hypocrites. Uh, no, wait. It’s…”

“It’s Monhegan Island!” Holladay exclaimed. I wanted to crawl down into the cockpit locker and hide like a stowaway. He then peppered me with questions about its bearing and the course to sail there. I stared blankly. “Watch this,” he said. He stretched open his wide hands and pressed them together with palms touching. Holding them stiff and straight, he laid them across the chart between the buoy we just passed and Monhegan. Then, slowly, methodically, keeping his hands aligned, he walked the straight, rigid palms across the chart to the closest compass rose. He was using his hands as a parallel rule. We sailed the rest of the day like that. He showed me again and again, and had me practice it.

After a while, he reached down again and came up with a little notebook. It was the cheap kind held together with a spiral of wire and small enough to drop into your shirt pocket. “This,” he explained, “is my dead reckoning plot. Every time I go out, I keep a plot like this.” I stared at the page.

“Enter your dead reckoning data regularly,” he said, “Every hour on the hour. Every course change, every speed change, the precise time you obtain your fix.”

I stared at the writing: Started engine. Running 1800rpm, temp 180deg, charge 13.5amps. At 1215 with Brenton Reef Lt. bearing 000deg, distant 200yards, took departure for Buzzard’s Lt. on course 096deg True, speed 5 knots. At 1325 changed course to 176deg and speed to 7 knots…. “You keep your plot like this, and you can’t go wrong,” he said emphatically. With that, he put down the notebook and resumed his stance in the companionway.

We sailed all day, going over the charts, the symbols, and the basics of dead reckoning. Once, when I looked up from the chart, Lou was standing in the companionway, looking out over the water. He was sipping from a can of iced tea and munching one of my prized Nabisco Crown Pilot Crackers. By now, Lou seemed content to let my son and me run the boat ourselves. I was gaining confidence in my new navigational skills at the same rate that Lou was consuming the Crown Pilot Crackers.

When we got back and put the boat away, Lou asked whether we were ready to go out without him. In his own unique way, with a teaching method that owed more to the Marine Corps than a Montessori School, Lou Holladay had taught me the basics of coastal navigation. Yes, he was blunt and direct. But beneath it all, I recognized a caring soul and a desire to share knowledge he had gained over so many years. I told him I was ready and he said he’d see me next Sunday.

We left the next morning and sailed into Muscongus Bay. From there, we went up the Muscle Ridge Channel to Rockland. In Pulpit Harbor on North Haven, we saw the old osprey nest atop the rock at the head of the harbor. Then we headed for Port Clyde. I replenished my dwindling supply of Pilot Crackers at the Port Clyde General Store, and my old friend David joined us for the trip back to West Boothbay.

Within minutes of leaving the harbor, a choking thick fog closed down on us. The fog was so dense, we couldn’t see more than six feet in front of our bow. Using the skills Lou had taught us, we picked our way from buoy to buoy and made it into New Harbor. The next day the heavy fog still lingered. Using the chart, watch, compass, and Lou’s two-handed parallel ruler method, we got the boat safely into Boothbay, past the swing bridge, and secured to Lou’s mooring.

I climbed the hill to check in with Lou. There was no high praise waiting for me. No hearty congratulations on getting the boat through the fog. No “Well done, lad. Now you’re a real sailor.” But beneath his rough exterior, I knew Lou was pleased.

There aren’t many men like Lou Holladay to navigate the waters ahead of us anymore. His kind is disappearing into the mists of time. All we can do now is navigate past shoals and islands, explore rivers and harbors, and share these experiences with passion and generosity and a love of sailing and the sea.

Lawrence Smith lives in upstate New York. He sails out of Noank, CT. With retirement on the horizon, he intends to follow in the wake of Lou Holladay, and sail the coast of Maine.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.