Photographs by Catherine Schmitt

Common periwinkles browse the surface of rockweed fronds.

Common periwinkles browse the surface of rockweed fronds.

The abundant shells, purple-brown, white-striped, golden-yellow, pepper the mudflats and form windrows along the beaches. Short-spiraled, shiny when wet, they call to be collected, and I answer. There are periwinkle shells on my windowsills, in a dish atop the bookshelf, in the center console of my car, in pockets, purses, and flowerpots. Burdens of a beachcombing habit, the shells dry to a duller, paler version of themselves. Still, I pick them up.

Periwinkles are so common along our shore that it’s easy to take them for granted. But these small marine snails have interesting stories to tell. Any investigation quickly reveals two facts. First: there are three distinct periwinkle species in Maine:

■ Rough periwinkle, Littorina saxitalis, has a delicately ridged spire with a sharp point, lives in the upper intertidal zone, and carries its eggs within its shell.

■ Smooth or flat periwinkle, Littorina obtusata, has a small, blunted shell in varied colors, lives among rockweeds, and lays eggs in jelly-like masses.

■ Common periwinkle, Littorina littorea, or “winkle,” grows a dark shell as large as two inches, lives in the middle and lower intertidal zone, and releases eggs into the sea. This is the most abundant and unmistakable of the three.

Here enters the second fact: The common periwinkle did not originate on these shores—some might even call it invasive.

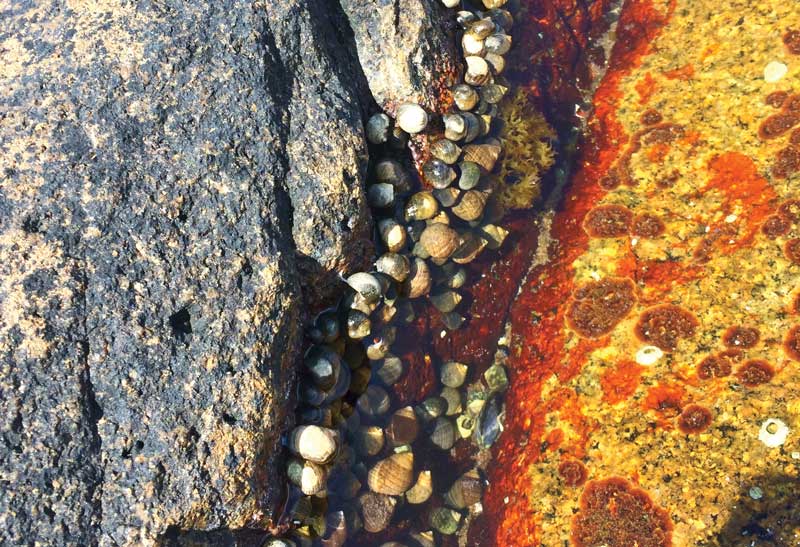

At low tide, common periwinkles crowd into water-filled pools and crevices, sometimes at high densities.

At low tide, common periwinkles crowd into water-filled pools and crevices, sometimes at high densities.

The origins of the common periwinkle

Shell-crazed naturalists first documented Littorina littorea at Pictou, Nova Scotia, in 1840. Later observations tracked its spread south: to Maine in 1868, Cape Cod in 1879, and Cape May, New Jersey, by 1890. Its sudden appearance, and rapid range expansion, suggested the species was introduced to North America.

Or not. In the 1960s, archaeologists found Littorina littorea shells at Indigenous sites in Nova Scotia that were thousands of years old.

For marine biologists in the North Atlantic region, resolving the origin of the common periwinkle became one of the most controversial debates of the last century. Maybe Littorina littorea was always here, and expanded as temperatures warmed? Or did Vikings bring their strandsnigel as a snack? Did the French carry les bigourneau from Brittany? Did winkles float west on a piece of driftwood?

All along the shores of Pictou are rounded rocks covered with periwinkles and toothed wrack, Fucus serratus, a European seaweed, said Dr. Susan Brawley, biologist and University of Maine professor. Her research on periwinkles has taken her around the North Atlantic rim. She has examined specimens of plants and shells in botanical gardens and natural history museums, viewed 19th-century paintings of the shoreline in art galleries, read newspaper accounts of ship traffic and cargo lists in libraries and archives, and collected snails from miles and miles of shoreline.

Genetic analysis of North American periwinkles pointed to ancestry in Great Britain. A sharper signal came from Fucus serratus (because fertilized eggs settle close the parents), showing links to Galway, Ireland, and Glasgow, Scotland, allowing Brawley and her colleagues to construct a history that includes the French Revolution, the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, and decades of war that disrupted the supply of timber from Baltic Sea ports. The English, desperate for wood to maintain their naval power, turned to the vast forests across the Atlantic. Ships left the British Isles loaded with cobble, dredged from the intertidal zone and used as ballast to balance vessels during the long sail. Once at Pictou, to make room for the lumber to be carried back, these ships unloaded their ballast into the harbor. The dumped rocks bore their own Scots-Irish colonies of toothed wrack and winkles.

With its warmer water and ice-scoured shores, Pictou was a suitable and blank slate, while the periwinkle’s adaptation to the varied temperature, light, and oxygen levels of the intertidal zone made it a hardy traveler. Over and over, the ships came in, discharged their ballast, loaded up with timber, and departed—some 882 European ships entered Pictou Harbor from 1773 to 1861, introducing enough periwinkles to enable reproduction and population growth.

Rough periwinkles, Littorina saxitalis, graze microscopic foodstuffs from rocks in the upper intertidal zone.

Rough periwinkles, Littorina saxitalis, graze microscopic foodstuffs from rocks in the upper intertidal zone.

Interactions in the intertidal

Today, the common periwinkle is the dominant herbivore in the Northeast rocky intertidal zone. And it can be very common, crowding the seams of fractured bedrock, filling tidepools, gliding along every surface.

Common periwinkles feed heavily upon the bladed and fleshy algae with a tongue-like radula covered in microscopic teeth. They nibble at sea lettuce, punch holes in the laver, and scrape up detritus, diatoms, spores, and germlings of Fucus and Ascophyllum. At high densities, periwinkles consume all the leafy and filamentous algae while leaving only the toughest, crusty forms. They also eat marsh grass, and “bulldoze” sediment from cobble beaches, removing mud that otherwise might become salt marsh. They can even file away the rock itself.

Where rockweeds settle in between rocks or barnacles, and grow taller than a centimeter, they are safe from the periwinkle’s rasp. The snails then browse the rockweed’s outside, keeping it clean, allowing it to flourish.

Before the arrival of Littorina littorea, the rocky shore of Maine was likely more colorful, with patches of green and red algae, and more pockets of marsh. Perhaps the other periwinkles, the smooth and the rough, were also more abundant.

Now, the common and smooth periwinkles compete for food. Littorina littorea’s voracious grazing prompts rockweeds to increase bitter tannins in their fronds as a defense, making smooth periwinkles travel farther for palatable food. The resulting increased exposure to the sun may be why their shells took on a lighter hue.

Rough periwinkles avoid competition by living at the upper edge of the shore, where roots and rock are strewn with dried, leathery strands of wave-tossed weed. On a cloudy day, they emerge to feed without risk of the sun’s drying heat, slowly lapping diatom films from cool stone.

Smooth perwinkles, Littorina obtusata, have shells in different colors including green and yellow.

Smooth perwinkles, Littorina obtusata, have shells in different colors including green and yellow.

There’s more to learn from periwinkles

Is it any surprise that periwinkles aresome of the most thoroughly studied marine snails in the world, the subject of thousands of scientific articles?

Within a square meter of shoreline, in the microbustle of snails in the intertidal metropolis, an inquisitive mind can wander across the history and ecology of life on Earth.

For example, where did plants and animals find refuge during the last ice age? The rough periwinkle’s family tree points to parts of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, and the mudflats and marshes south of Long Island.

How do isolated populations maintain the diversity that gives rise to new species via natural selection? The periwinkle’s polyandrous sex life suggests one way. Unlike most animals, the male periwinkle is the choosy one, selecting a mate from among competing females. But a single female may pair with up to ten males, multiplying genetic variation in her young.

All the Littorina are highly adaptable. The shell, which came to be some 500 million years ago in response to increasing predator diversity, continues to evolve. Thick layers of calcite and aragonite add strength, while the rounded shape makes it harder for crabs to catch hold. Where crabs are abundant, periwinkles have thicker shells with smaller shell apertures but deeper cavities. If the threat is too great, periwinkles withdraw into their shells, their mucous hardening to firm attachment. If periwinkles survive predation by crabs, gulls, flounder, and boring sponges, they can live as long as 10 years.

Their captivating crawl is also an adaptation to these shores, a trait shared with all snails.

“My snail was downright savvy,” wrote Elisabeth Tova Bailey in The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating (Algonquin Books, 2010). “Some of its active defenses were so subtle that I wasn’t even aware they were strategic...A snail’s slow locomotive speed makes it seem vulnerable, but may actually be a survival method, saving it from predators whose hunting activity is triggered by fast movement.”

There are hints, however, that the common periwinkle’s survival skills are failing. A recent study from Swan’s Island, Maine, documented a 20-year decline in periwinkles correlated with warming temperatures. It will take time to see if these findings hold for the rest of the coast.

To watch periwinkles, I have to pause, and soon I am mesmerized. Tentacles search the air and taste the ground. The muscular foot spreads out. With its whole body, the periwinkle moves its heavy shell over bladderwrack hills and down granite cliffs. Mucus provides traction, and leaves a wet trail, a signal to other snails. What messages are being sent and received?

In late winter, Littorina littorea emerges from the subtidal zone, where it has spent the cold season in a kind of hibernation. The soft head appears from its round doorway, ready to re-engage with the world. It joins the dense herd of periwinkles moving up the intertidal zone, feeding on the thick turf of green algae that grew over the winter, clearing the way for barnacle larvae which, a few weeks later, will drift in and settle to the rocks.

The periwinkles will spread out to find their niche for the summer, and I will rush to meet them. At a snail’s pace, of course.

✮

Catherine Schmitt is a science communication specialist with Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park.