Dreamboats From the Past

A Pipe Dream sloop and a vintage Trumpy

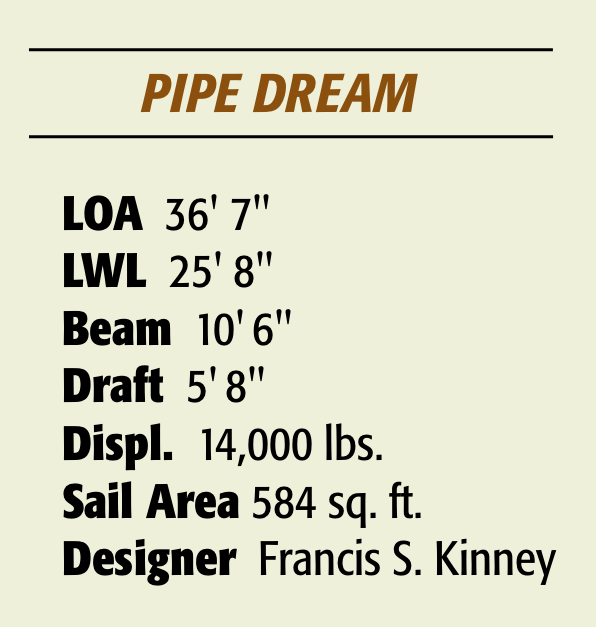

For this issue, I get to feature two yacht designs of old that I particularly love, one a sailboat and one a powerboat: the Pipe Dream sloop designed by Francis S. Kinney and a 79' Trumpy named Rumak III. These boats are so much a product of long ago that some might claim they lack rele-vancy. I disagree. If you were to commission a boatyard to build either one, and were you to plunk it in all its freshly outfitted glory alongside its modern counterparts, both these oldies would eclipse many of today’s best-known designs.

The Pipe Dream sloop’s large cockpit, stable feel, and helm make the boat lovely to sail. Photo courtesy Mory Creighton

Let’s start with the Pipe Dream sloop. Kinney worked as a designer/ draftsman for Sparkman & Stephens during what many considered to be that firm’s heyday.

The Pipe Dream sloop’s large cockpit, stable feel, and helm make the boat lovely to sail. Photo courtesy Mory Creighton

Let’s start with the Pipe Dream sloop. Kinney worked as a designer/ draftsman for Sparkman & Stephens during what many considered to be that firm’s heyday.

The Pipe Dream design, however, was not instigated under that firm’s umbrella. Instead, it came out of a book commission. When the publisher Dodd, Mead & Co. decided to update Norman L. Skene’s Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design, the company chose Kinney for the rewrite. The goal was to incorporate post-World War II lessons and new technologies. Kinney went so far as to invent an ideal “pipe dream” cruising sailboat especially for the book. Using this boat as an example, he took the reader through all the relevant drawings and calculations involved in accomplishing a completed design.

Because I aspired to become a yacht designer when I was young, I studied Skene’s again and again, and I was smitten with Kinney’s pretty Pipe Dream.

Excellence doesn’t inevitably lead to fame or fortune. Kinney only sold a few sets of Pipe Dream plans to a few discriminating romantics who had the means to build a boat. There were Pipe Dreams built plank-on-frame in America, a couple built with cold-molded wood in South Africa, others out of steel in Holland and Belgium, and even a single example using ferro-cement in Vancouver, Canada.

The design came back into my life in the 1980s. I was working at Bass Harbor Marine as a rigger and sailboat captain when I learned that boatbuilder George Patten, of Kittery, Maine, was going to build a couple of fiberglass Pipe Dreams for our boatyard to market. The boats were built and we sold them, but astoundingly to me, the product didn’t take off. In all, Patten built only four hulls.

The design came back into my life in the 1980s. I was working at Bass Harbor Marine as a rigger and sailboat captain when I learned that boatbuilder George Patten, of Kittery, Maine, was going to build a couple of fiberglass Pipe Dreams for our boatyard to market. The boats were built and we sold them, but astoundingly to me, the product didn’t take off. In all, Patten built only four hulls.

Imagine my delight when I was hired as a summertime captain on one of the Bass Harbor Pipe Dreams. One of my assignments was to teach the owner to varnish, and we spent many a happy hour in the middle of Southwest Harbor, doing that and other nautical tasks while listening to the Iran Contra hearings on a portable radio. Mostly, though, we sailed.

What a marvelous sailer that boat was. The keel was quite far aft, leaving an unusually large distance between the sails’ center of effort and the keel’s center of lateral resistance. If everything isn’t in proper balance, this can cause lee helm in light winds, but the Pipe Dream was a joy to helm to windward in any strength of breeze. The rig in the boat is masthead, and unusual in that the mast is comparatively short. Although I never was able to convince my employer to try racing, I knew that this boat would rate as a “rule-beater,” mast height being a dominant handicap-rating factor. A second efficiency that impressed me was that the keel was more airfoil shaped than most of that time. In addition, there was a bit of bulb-like swelling toward the bottom.

The Creighton family of Maine and Massachusetts has owned this Pipe Dream, Narada, for 20 years. Photo courtesy Mory Creighton

I had read about all this emergent science in Skene’s and in yachting magazines in 1961, when I’d only begun to sail and race. At that time most races were run over a triangular course, in which short masthead rigs were the thing. For such courses, and yacht club cruise-races that involved a lot of reaching and running, short masthead rigs employed a spinnaker nearly as wide as high. A Pipe Dream could have hauled in the trophies. Low-packed sail plans like this are also preferred by many captains for reeling off unworried miles far out to sea.

The Creighton family of Maine and Massachusetts has owned this Pipe Dream, Narada, for 20 years. Photo courtesy Mory Creighton

I had read about all this emergent science in Skene’s and in yachting magazines in 1961, when I’d only begun to sail and race. At that time most races were run over a triangular course, in which short masthead rigs were the thing. For such courses, and yacht club cruise-races that involved a lot of reaching and running, short masthead rigs employed a spinnaker nearly as wide as high. A Pipe Dream could have hauled in the trophies. Low-packed sail plans like this are also preferred by many captains for reeling off unworried miles far out to sea.

The interior of the individual boat I skippered was well done, which should be credited to Patten, since it varied from the accommodation plan in the book. It had a nifty little loveseat, perfect for reading. The galley area spread fully across the widest part of the boat, and was very functional. The cockpit was extra roomy, with comfortable seating.

The Pipe Dream’s owner and I agreed that the best moments of our varnish-instruction days involved rowing ashore. We would circle around the boat, admiring the sheerline, and the way those squashed oval port lights almost magically diminished the appearance of freeboard.

The one thing about the boat that gave me pause was the shape of the bottom of the keel. I always wondered if it would “take the ground” successfully without falling onto its forefoot if someone was in the bow fiddling with ground tackle while the tide ebbed away. I never did find that out, since I kept that treasured beauty safely within soundings.

Eventually the owner moved to Florida and later sold the boat, but he presented me with a beautiful painting that hangs in my living room. Looking at it reminds me of the great times I had aboard. Anticipated love doesn’t always turn out to be what one envisioned, but the Pipe Dream was all I’d ever dreamed her to be, and more.

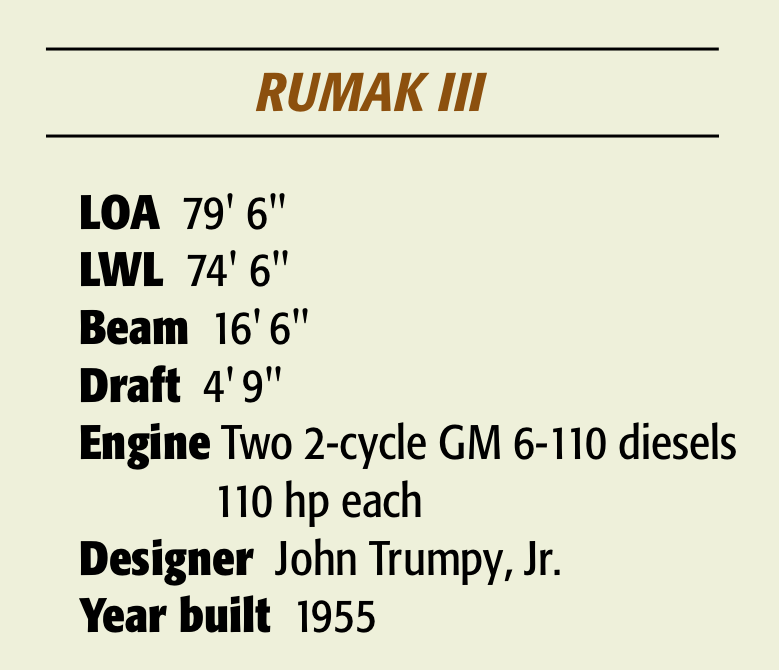

Now beautifully restored, this Trumpy, which began life named Rumak III, is now called Annabelle and spends summers cruising Penobscot Bay. Photo courtesy George Greider

Now beautifully restored, this Trumpy, which began life named Rumak III, is now called Annabelle and spends summers cruising Penobscot Bay. Photo courtesy George Greider

Love on a grander scale: the Trumpy Rumak III

When I was young, my keen interest in boats was undifferentiated by type—I loved everything afloat. The essence of this fascination involved appearance. My twin brother and I liked to draw, and our attraction to boats was inspired by their beauty, rather than their performance.

I discovered the specialness of Trumpy poweryachts while poring through early boating magazines in search of vessels to draw. Even at that young age, I could define small distinctions between a Grebe and a Stephens, a Burger and a Feadship, a Chris-Craft and a Matthews. One major consideration was that some of these others were fashioned out of material other than exquisitely double-planked wood. Maybe I’m wrong, but the way I recall it, my brother Chuck and I could discern a bespoke wooden poweryacht from a nautical mile away.

I discovered the specialness of Trumpy poweryachts while poring through early boating magazines in search of vessels to draw. Even at that young age, I could define small distinctions between a Grebe and a Stephens, a Burger and a Feadship, a Chris-Craft and a Matthews. One major consideration was that some of these others were fashioned out of material other than exquisitely double-planked wood. Maybe I’m wrong, but the way I recall it, my brother Chuck and I could discern a bespoke wooden poweryacht from a nautical mile away.

Trumpy designs had evolved into two styles, flush-decked “houseboats” and somewhat sleeker “express cruisers,” which were split-level with a pilothouse aft on a higher level. In either configuration, we aspiring artists insisted that a graceful poweryacht looked finest atop the blue sea when its hull was white, the middle field brown—as in varnished mahogany—and the cabintops white again. While all Trumpys qualified, many other fine poweryachts didn’t. Huckins Fairform Flyers, for instance, were superbly efficient powerboats but they displeased us, being entirely coated in paint.

Rumak III was designed, as all of them were, by John Trumpy, with a lot of assistance from Frederick Geiger, whose influence shows particularly in the “express cruisers.” This was a special Trumpy because the owner wanted an extremely quiet, easily-driven boat. Therefore its underbody was exceptionally long and lean, the deadwood sculpted for minimal resistance, with, according to one Trumpy expert I interviewed, some anticipation of “wave-piercing” technology.

The fact that Rumak III was pushed up to 15.5 knots by just a pair of 110-hp GM diesels reveals how efficiently she glided down the Intercoastal Waterway. I doubt that this level of performance would have been possible had not the vessel’s scantlings been diminished a bit, but I was unable to discover the displacement, and whether it was less than others of comparable size. For noise reduction, the engines were provided with the utmost in soft mountings, rubber couplings, and the latest in exhaust-silencers. John Trumpy had recently experimented and found that five-bladed propellers produced the least vibration, so this boat had them.

These details weren’t of the slightest interest to me at the time, however. I just fell for this boat’s looks. Every Trumpy was different, and even a kid could tell that this one looked more like a “commuter” than most. There was more of the out-stretched hull and less superstructure. Of course, this was a time when all Trumpys had a white hull with a varnished sheer strake aft, gold-leaf in all the right places, stretched white canvas lifeline “weather cloths” athwart the aft cockpit, and a wooden mast upon which to display flags that were meaningful in some way to yachtsmen. Varnished transoms were optional. Rumak III had one, but truth to tell, even a fanatical marine artist like me can’t decide whether white paint looks better.

I made sheaves of sketches of Rumak III and did a couple of oil paintings using left over trays of paint from my paint-by-numbers sets.

Rumak III had at least five owners after William “Mac” McKelvy. At one point this fine yacht was abandoned in a Florida river, and actually had a tree growing through the topsides. A former owner saved her, and subsequent buyers continued the healing. More restoration down south brought the boat, under the names Wind Song II and Osceola, to seaworthy shape. Finally the boat came to Maine, for the ultimate refit at the Hinckley yard in Southwest Harbor.

The best part is this: My old love, Rumak III, now named Annabelle, spends the summer off Islesboro. I can hop in my sailboat armed with a watercolor set and paper, and sail around and around her. You better believe that’s on my bucket list.

Contributing Author Art Paine is a boat designer, fine artist, freelance writer, aesthete, and photographer who lives in Bernard, Maine.

Learn more about the Creighton family’s sailing adventures in Narada at maineboats.com.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.