Water Ways: Navigation

By Melissa Waterman

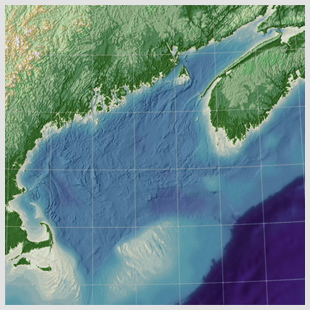

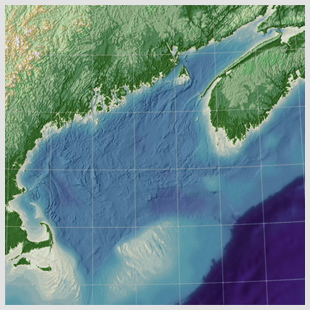

Courtesy of Gulf of Maine Aquarium/GMRI Hey there all you gizmo-loving explorers! Put down your hand-held GPS units. Give up your Map Quest bookmarks. Say good-bye to the intricacies of LORAN. There’s a great old-fashioned way to find your way around Maine and its coast. It’s called a map (or a chart if you are on the water) and woe to the poor soul who doesn’t know how to use one.

This past year a half-dozen people arrived at my doorstep thanks to the GPS unit embedded in their car. I even enjoyed a brief and peculiar conversation with both a young woman and her car's GPS as she was headed to Rockland. The dialog went something like this:

“You want to take the first Brunswick exit to get onto Route 1,” I said.

“Continue for one and three-quarters mile to Exit 30,” demanded the monotone GPS voice.

“What?” said the woman.

“Don’t take the second exit, take the first,” I explained.

“But he says that’s not right.”

“He who?”

“The computer.”

“Turn right, Exit 30,” came the voice again.

“Um, well, I do live here. He doesn’t.”

The woman hung up.

I have given blow-by-blow telephone directions to people calling from their cars while they turned left, right, and then left again to arrive in my driveway, unable to negotiate the few short blocks from Main Street to my house. I have had people defiantly tell me that they knew exactly where the ferry terminal was located, rev their car's motor, and then head west toward the mountains, rather than east to the harbor. One couple was rather indignant when they arrived here because the GPS unit in their car had not told them that Route 1 in Thomaston was closed to traffic. “We went off on a detour! I have no idea where we were,” said the woman.

Courtesy of Gulf of Maine Aquarium/GMRI Hey there all you gizmo-loving explorers! Put down your hand-held GPS units. Give up your Map Quest bookmarks. Say good-bye to the intricacies of LORAN. There’s a great old-fashioned way to find your way around Maine and its coast. It’s called a map (or a chart if you are on the water) and woe to the poor soul who doesn’t know how to use one.

This past year a half-dozen people arrived at my doorstep thanks to the GPS unit embedded in their car. I even enjoyed a brief and peculiar conversation with both a young woman and her car's GPS as she was headed to Rockland. The dialog went something like this:

“You want to take the first Brunswick exit to get onto Route 1,” I said.

“Continue for one and three-quarters mile to Exit 30,” demanded the monotone GPS voice.

“What?” said the woman.

“Don’t take the second exit, take the first,” I explained.

“But he says that’s not right.”

“He who?”

“The computer.”

“Turn right, Exit 30,” came the voice again.

“Um, well, I do live here. He doesn’t.”

The woman hung up.

I have given blow-by-blow telephone directions to people calling from their cars while they turned left, right, and then left again to arrive in my driveway, unable to negotiate the few short blocks from Main Street to my house. I have had people defiantly tell me that they knew exactly where the ferry terminal was located, rev their car's motor, and then head west toward the mountains, rather than east to the harbor. One couple was rather indignant when they arrived here because the GPS unit in their car had not told them that Route 1 in Thomaston was closed to traffic. “We went off on a detour! I have no idea where we were,” said the woman.

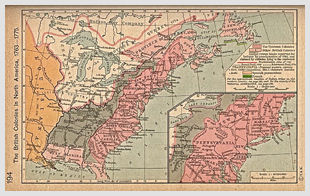

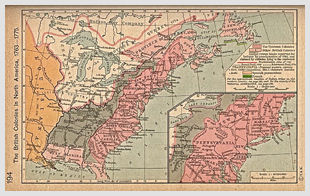

Courtesy of University of TexasWhen I was a child, my sister and I would set off on epic summer journeys from our home in rural Rhode Island. These adventures would require a bag of sandwiches, Oreo cookies and ginger ale, and a promise to return before dark. We would march off over the fence into the neighbor’s corn field and make our way to some known site: a boulder set in the woods, the marsh that butted up to the beach, perhaps one of the long-forgotten World War I bunkers that remain scattered along the Rhode Island coast. We planned our route like great Arctic explorers, drawing maps and estimating time. Sometimes it would take the better part of the day and a fair bit of scrambling to get to whatever spot we had in mind. Sometimes we didn't make it at all (but had a fine lunch). I think that’s when I learned to navigate.

Navigate is a word most often used in association with the ocean. But we all navigate when we're wandering about a strange city or setting off on a driving vacation. In those instances I am both master and navigator of one vessel – myself – and I am pleased to say that I can plot my course without the use of a GPS unit.

That’s not to say that GPS units aren’t pretty nifty objects. Global Positioning Systems came into the civilian marketplace in the mid-1990s; the United States military was using orbital satellite navigational systems from the 1960s onward. The current global positioning system operated by the Department of Defense comprises up to 32 satellites in six different orbits around the earth. The orbits are arranged so that at any moment at least four satellites are in the sky above any point on the earth. The satellites emit radio signals that are picked up by a GPS receiver. The receiver knows the time, location, speed, and direction of the moving satellites and can find its own position based on signals from at least three satellites. The receiver then translates that data into a visual representation (a map) or simple latitude-longitude coordinates.

Right now, the United States is the only country in the world that operates a global positioning system. Russia is still putting together its GLONASS satellite system; China and India are creating similar navigational systems as well.

I confess that I have never used a GPS unit -- I like maps and charts. I enjoy the multitude of information contained on every sheet. I even like the feel as I smooth one out beneath my hands.

A map is its own hyper-link. You look at one road or mountain range and it may lead you you to the north, where you find an intersecting road that wanders through a town you’ve never visited or across a valley full of wild rivers. On a navigational chart you locate your town and then, for the fun of it, trace a hypothetical journey to some other harbor for which one day you might set sail.

A paper map allows you to place yourself in context on the earth, without the aid of satellites or voices droning from your dashboard. Using the most complicated of computers, the human brain, it is possible to find your way in the world.

Courtesy of University of TexasWhen I was a child, my sister and I would set off on epic summer journeys from our home in rural Rhode Island. These adventures would require a bag of sandwiches, Oreo cookies and ginger ale, and a promise to return before dark. We would march off over the fence into the neighbor’s corn field and make our way to some known site: a boulder set in the woods, the marsh that butted up to the beach, perhaps one of the long-forgotten World War I bunkers that remain scattered along the Rhode Island coast. We planned our route like great Arctic explorers, drawing maps and estimating time. Sometimes it would take the better part of the day and a fair bit of scrambling to get to whatever spot we had in mind. Sometimes we didn't make it at all (but had a fine lunch). I think that’s when I learned to navigate.

Navigate is a word most often used in association with the ocean. But we all navigate when we're wandering about a strange city or setting off on a driving vacation. In those instances I am both master and navigator of one vessel – myself – and I am pleased to say that I can plot my course without the use of a GPS unit.

That’s not to say that GPS units aren’t pretty nifty objects. Global Positioning Systems came into the civilian marketplace in the mid-1990s; the United States military was using orbital satellite navigational systems from the 1960s onward. The current global positioning system operated by the Department of Defense comprises up to 32 satellites in six different orbits around the earth. The orbits are arranged so that at any moment at least four satellites are in the sky above any point on the earth. The satellites emit radio signals that are picked up by a GPS receiver. The receiver knows the time, location, speed, and direction of the moving satellites and can find its own position based on signals from at least three satellites. The receiver then translates that data into a visual representation (a map) or simple latitude-longitude coordinates.

Right now, the United States is the only country in the world that operates a global positioning system. Russia is still putting together its GLONASS satellite system; China and India are creating similar navigational systems as well.

I confess that I have never used a GPS unit -- I like maps and charts. I enjoy the multitude of information contained on every sheet. I even like the feel as I smooth one out beneath my hands.

A map is its own hyper-link. You look at one road or mountain range and it may lead you you to the north, where you find an intersecting road that wanders through a town you’ve never visited or across a valley full of wild rivers. On a navigational chart you locate your town and then, for the fun of it, trace a hypothetical journey to some other harbor for which one day you might set sail.

A paper map allows you to place yourself in context on the earth, without the aid of satellites or voices droning from your dashboard. Using the most complicated of computers, the human brain, it is possible to find your way in the world.

Courtesy of Gulf of Maine Aquarium/GMRI

Courtesy of Gulf of Maine Aquarium/GMRI Courtesy of University of Texas

Courtesy of University of TexasRelated Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.