Winslow Myers in Motion

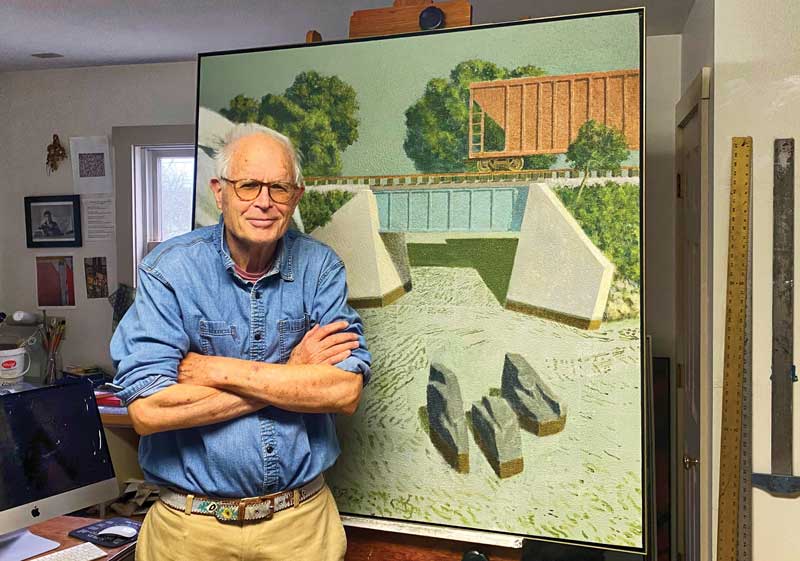

Winslow Myers in his Nobleboro studio with a work in progress on the easel.

Winslow Myers in his Nobleboro studio with a work in progress on the easel.

“I’m drawn to art that speaks for itself,” Winslow Myers said during an interview in his studio in Nobleboro in mid-November, 2024. In support of this preference, Myers turned to one of his favorite artists, the French Cubist Georges Braque: “There is only one valuable thing in art: the thing you cannot explain.” To further make his point, he cited the words of another art hero, Edward Hopper: “If I could say it in words, there would be no reason to paint.”

If Myers looks askance at art that requires a lot of explication, his own work often embraces enigma, most notably in the “Passages” series painted between 2002 and 2017. Each of the 29 “split image” acrylic paintings, averaging around 60 by 60 inches, challenges the viewer to consider contrasting scenes side by side: the bow of a sailboat, say, and a snowy railroad bridge. Working from a “collage of fragments”—some from visual memory, some from photographs, some improvised—Myers seeks to create novel arrangements that engage the eye and mind, and elicit surprise.

In his “Passages” series, Myers seeks to engage the eye and mind while eliciting surprise. Passages #22, 2013, acrylic on two panels bolted together, 60 x 60 inches.

In his “Passages” series, Myers seeks to engage the eye and mind while eliciting surprise. Passages #22, 2013, acrylic on two panels bolted together, 60 x 60 inches.

Scanning the series on Myers’s website, winslowmyers.com, one encounters many images related to transportation, including railroads and airplanes. His love of the former derives, in part, from a childhood memory of riding in a sleeper car from Princeton, New Jersey, to Newcastle, Maine (the train went on a barge across the Hudson River). He has also never gotten over “the wonder” of being above the clouds in a plane.

In Myers’s “Carscape” series, the windshield functions as a frame within a frame. Carscape 3, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 46 x 34½ inches.

In his shift to single-panel paintings, Myers has maintained the focus on passing through the world by way of an intriguing mix of imagery. His solo exhibition at the Bromfield Gallery in Boston, Massachusetts, last year, “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” featured several “carscapes,” or views of Maine and elsewhere as seen from the driver’s seat. “I’m always looking for the combination of the manufactured and the natural,” he noted, and he likes how windshields function as a frame within a frame. He had made several of these paintings when he came across a similar motif in “America by Car,” a series by Lee Friedlander, one of his favorite photographers.

In Myers’s “Carscape” series, the windshield functions as a frame within a frame. Carscape 3, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 46 x 34½ inches.

In his shift to single-panel paintings, Myers has maintained the focus on passing through the world by way of an intriguing mix of imagery. His solo exhibition at the Bromfield Gallery in Boston, Massachusetts, last year, “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” featured several “carscapes,” or views of Maine and elsewhere as seen from the driver’s seat. “I’m always looking for the combination of the manufactured and the natural,” he noted, and he likes how windshields function as a frame within a frame. He had made several of these paintings when he came across a similar motif in “America by Car,” a series by Lee Friedlander, one of his favorite photographers.

Over the years, Myers has featured sailboats in a number of his paintings. He traces his interest in this subject to boyhood outings with his father on his yawl Godwit on the Damariscotta River. “It was a beautiful boat,” he recalled, “just a little breeze and go.”

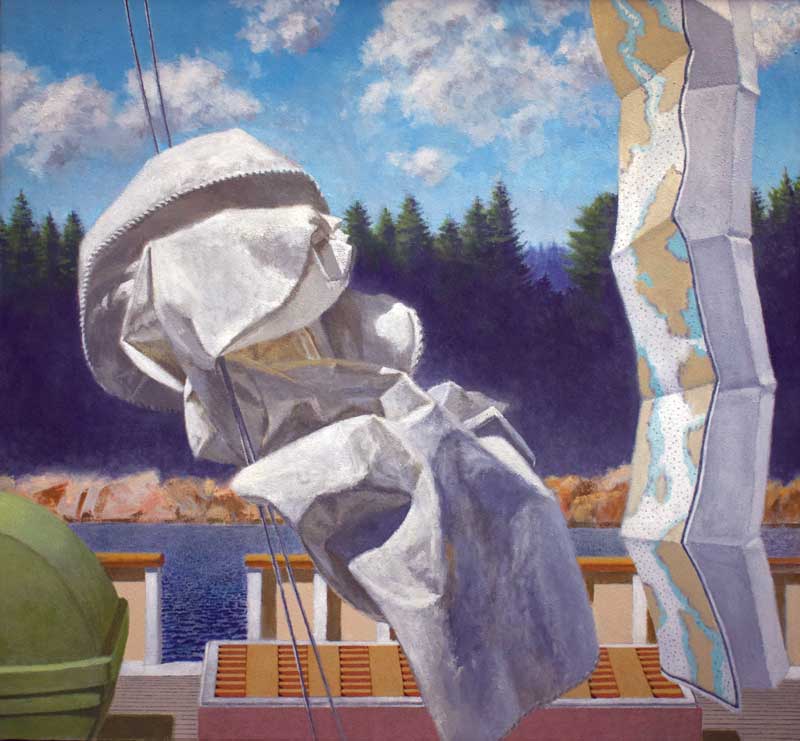

In Floating Sail and Chart, 2022, the canvas is crumpled up. Myers credits his teacher and mentor, Canadian-born painter Walter Murch (1907-1967), for this “drapery” presentation. In his brilliant still lifes Murch could turn a scrap of cloth into the shroud of Turin. Myers has tried, in his words, “to lean in that direction: art as a visual poetry, as a celebration of the mystery of reality.” He has an old piece of sail and photographs it in different positions when he needs it.

In many of his paintings, Myers celebrates the mystery of reality. Floating Sail and Chart, 2022, 44 x 48 inches.

In many of his paintings, Myers celebrates the mystery of reality. Floating Sail and Chart, 2022, 44 x 48 inches.

Myers works out of a modest space that he shares with his wife, fellow artist Patti Bradley. During the November visit, a new canvas featuring a railroad overpass stood on the easel. In the course of conversation, he pulled out a number of paintings, including several portraits of family and friends.

The rail line that runs past their home has served as a motif in a number of Myers’s paintings. Until its recent downsizing, the Dragon Cement plant in Thomaston used the railway a couple of times a day.

Myers and Bradley travel to Belize to visit family nearly every winter. One of their grandchildren from that clan now lives with them while attending nearby Lincoln Academy. “She keeps us going,” Myers said.

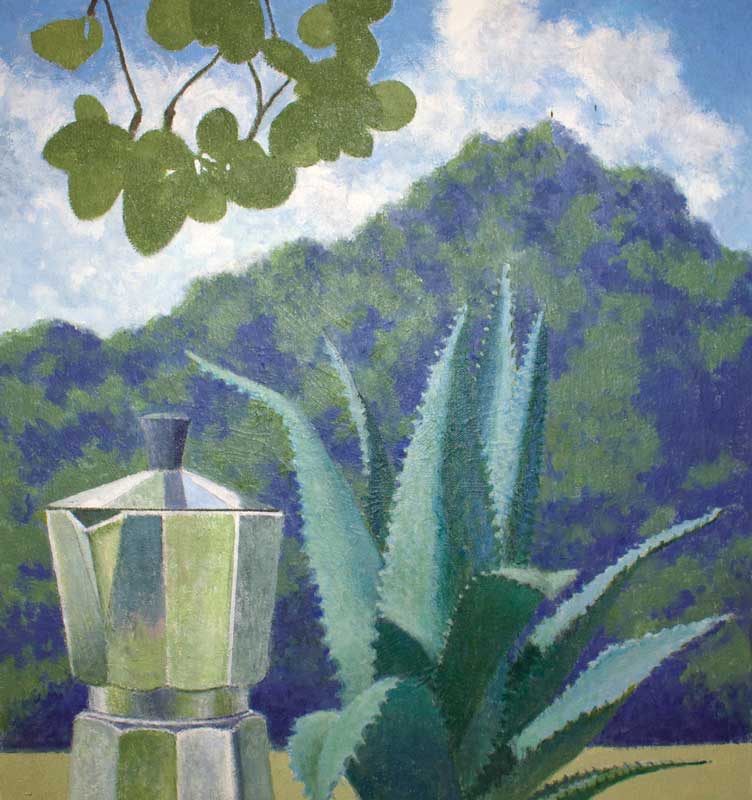

While in Belize, Myers sets up a studio in the rental and works on small pieces. The countryside appears here and there in his paintings, including an ethereal still life/landscape featuring a coffee pot and an agave plant.

The trips to Central America have heightened Myers’s love of the contrast between tropical and temperate, a passion he relates to the poetry of Wallace Stevens, an important influence on his world view. Lines from the poem “Farewell to Florida” come to mind: “How content I shall be in the North to which I sail / And to feel sure and to forget the bleaching sand.”

Myers channels René Magritte in the surreal painting Low Sunlight, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 45 x 38 3/8 inches.

Myers channels René Magritte in the surreal painting Low Sunlight, 2024, acrylic on canvas, 45 x 38 3/8 inches.

A Youthful Move to Maine

Born in New York City, Myers moved with his family to Walpole, Maine, in 1949 when he was 8 years old. His father, who had been a fundraiser at Princeton University, started a mail-order lobster business. “He bought a full-page advertisement on the inside back cover of the New York Times Magazine,” Myers recalled, “and never looked back.” The Boston-Maine railroad would load barrels of lobsters and clams onto a car every day for the trip south.

While attending Philips Exeter Academy, Myers was exposed to art. He was especially excited by the modernist painter John Marin, how his “handwriting” could represent the Maine landscape in such a vital way. Another discovery from that time: poet Robert Frost who visited his class. “There were 12 students in a circle and him at one end,” he recalled, “and we were just struck absolutely dumb.”

In his senior year at Exeter, Myers made a clay bust of Ernest Hemingway. With the help of the Exeter News-Letter staff, he cast the likeness in molten linotype metal. The bust appeared in the inaugural exhibition of the Maine Art Gallery in Wiscasset in 1958, quite a debut for the 17-year-old as he joined an esteemed group of contemporary artists, among them Dahlov Ipcar, William Thon, Bernard Langlais, Denny Winters, and William Kienbusch.

Myers went on to Princeton where, in his words, he “treaded water” for four years (1958-1962). Visiting artists such as Hyde Solomon and Stephen Greene would come down from New York City for a semester, but there was no art major at the time. His favorite professors were in the English department and included poet R. P. Blackmur and Frost biographer Lawrence Thompson.

The painter also recalls attending a birthday party for the son of J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. When the famed physicist learned of Myers’s interest in art, he ushered him into his windowless study to show him original works by Renoir, Dürer and, over his desk, van Gogh’s Wheatfield at Sunrise, 1889, the view from the artist’s room in the asylum outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Myers has never forgotten that viewing.

Upon graduation, Myers spent a year in Greece teaching English. Returning stateside in 1963, he moved to Mount Desert Island to teach at Pemetic High School in Southwest Harbor. He remembers people saying that anyone who came from away to the island for the winter “must have done something terrible elsewhere.”

The next year Myers enrolled at Boston University, recommitting himself to painting. During that time, he studied with the aforementioned Walter Murch. Sadly, his mentor and friend died of a heart attack while in New York City to raise funds for the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. More than a half-century later, in 2023, Myers teamed up with the artist’s family, several art historians, and famed filmmaker George Lucas to produce a remarkable monograph, Walter Tandy Murch: Paintings and Drawings, 1925-1967 (Rizzoli).

During visits to Belize, Myers paints smaller pieces related to his tropical surroundings. Landscape/Still Life, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 19½ x 18 inches.

During visits to Belize, Myers paints smaller pieces related to his tropical surroundings. Landscape/Still Life, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 19½ x 18 inches.

Several painters followed Murch at BU, including Philip Guston and John Moore. Finishing his studies there, Myers received a Max Beckman Fellowship at the Brooklyn Museum School. The fellowship proved to be something of a bust so he transferred to Queens College where he earned an MFA.

Returning to Boston, Myers sent out applications “all over the place” looking for a teaching job and got one hit: Bancroft Academy, a private K-12 school in Worcester, Massachusetts. Teaching mainly in the high school, he spent the next 30-plus years there as chair of visual arts. He also taught drawing and painting at Assumption College, and art history and foundation drawing at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Myers married Charlotte Josephine Kenner Hart in Newcastle, Maine, in June, 1973. They had two children, Anna and Chase, and lived in Paxton, Massachusetts.

While he had early success through the Kennedy Gallery, one of New York City’s pre-eminent art venues, with a family and a full-time teaching job Myers found it difficult to find time to paint. He taught nights and summers to supplement his income.

In the mid-1980s, Myers began to write about the Cold War when, he said, the tension between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. was “intolerably high.” He was and remains angry that so many governments are intent on maintaining deterrence as a way to security when, he points out, “it’s a de facto system that cannot work forever.”

Supported by Beyond War, an activist group in California, Myers wrote extensively on the subject, only painting now and then. He has never stopped opposing war. In 2009 he published Living Beyond War: A Citizen’s Guide; Robert Ellsberg, Daniel Ellsberg’s son, was his editor. His columns appear in publications in Maine and elsewhere, including the Christian Science Monitor and the San Jose Mercury News.

When the Cold War drew to a close in the early 1990s, Myers returned to painting, shifting from oil to acrylics. Losing his son to a drug overdose in 2002 and his wife a year later, he felt a need to start over, which meant leaving Worcester. He moved around, living in Stowe, Vermont, Brookline, Massachusetts, and Japan before returning to Bristol, Maine.

Myers met his second wife, Patti Bradley, in 2014. They initially lived in Bristol where they set up a home gallery for their work, Petrel Fine Arts. They moved to Nobleboro in 2021, at the beginning of COVID.

Myers loves the new digs, the house, the railroad, the nearby water. During the studio visit he showed off an electric foil board he had recently purchased. Formerly a wind-surfer (until he broke his arm), he is determined to master this motorized hydrofoil.

Currently chair of the Nobleboro Democrats, Myers has served on the board of the Coastal Senior College and is an active member of his local Rotary Club. In a 2024 interview, he said, “There’s nothing like standing before the easel listening to Bach or Bob Dylan.” His passion for the latter extends to the bumper sticker on his pickup truck: “Dylan for President.”

After finishing the work for his solo show in Boston last year, Myers took time off from painting to finish his second book on the prevention of war, One—One Earth, One Humanity, One Future, for which he is looking for a publisher. He has since returned to the easel, once again seeking to create what he calls “visual poetry.”

“One wants to live the question: What is it that only painting can do, or that painting does best?” Myers stated at the time of his solo show at River Arts in Damariscotta in 2022. “In a sense all painting is still life,” he wrote, “silent, but alive on its own terms.” A quote from the Italian still-life painter Georgio Morandi summed up his outlook: “There is nothing more surreal and abstract than reality.”

✮

Carl Little’s most recent publications are Blanket of the Night: Poetry (Deerbrook Editions) and the monograph John Moore: Portals (Marshall Wilkes).

For More Information

More of Myers’s work can be found on his website, www.winslowmyers.com. He is represented by Yvette Torres Fine Art in South Bristol, Maine.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.