Men and women visitors appear equally armed and ready for whatever is in store for them in the Maine woods surrounding C.S. Cooks Camps on Holeb Lake’s Birch Island, southwest of Jackman. From Scenic Gems of Maine published by George W. Morris, Portland, 1898, courtesy Roger Allen Moody

Men and women visitors appear equally armed and ready for whatever is in store for them in the Maine woods surrounding C.S. Cooks Camps on Holeb Lake’s Birch Island, southwest of Jackman. From Scenic Gems of Maine published by George W. Morris, Portland, 1898, courtesy Roger Allen Moody

Buoyed by his travel experiences in Maine’s North Woods in the mid-1800s, Henry David Thoreau wrote widely about the values of nature and the physical and psychological renewal brought by life in the outdoors. That philosophy helped draw “rusticators” and “sports” to the lakes, streams, mountains, and the vast north woods from throughout the eastern United States during the post-Civil War era and extending to the 1930s.

The war, although filled with stresses and perils, had led to the development of new sources of wealth and an era of material prosperity. At roughly the same time, a new appreciation for the outdoors was evidenced by the likes of W.H.H. Murray and crusades for the “gospel of rest.” Murray (1840–1904), also known as “Adirondack Murray,” was an American clergyman and author of an influential series of articles and books, such as Adventures in the Wilderness; or Camp-Life in the Adirondacks that popularized upstate New York and caused him to become known as the father of the Outdoor Movement.

Lucius Hubbard’s introductory comments, meanwhile, in his 1893 Hubbard’s Guide to Moosehead Lake and Northern Maine, reflected these same themes: “To the care-worn businessman and overworked student, no relaxation from the constant wear of their respective callings is so grateful as that which comes while camping in the woods. … In the wild woods, life is regenerated, and even after two weeks of camping out and canoeing one issues forth with renewed strength for the work of the coming year. Rest and relaxation are an absolute necessity.”

Diners gather round a table in 1885 at Socatean Stream, a northwest tributary to Moosehead Lake. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Diners gather round a table in 1885 at Socatean Stream, a northwest tributary to Moosehead Lake. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In the late 19th century, a new, increasingly urban, middle class emerged that had more leisure time and disposable income than common people had ever enjoyed before. Eager to spend their income and newfound time outside the workplace, they turned to the outdoors and sports, either as participants or spectators.

The sporting camps of northern Maine responded by providing the services and skills necessary to experience nature at a primeval level, but at the same time offered a degree of the comforts clients customarily enjoyed in their urban settings.

Visitors to the sporting camps relied on the steamers like the Katahdin, in service on Moosehead Lake from 1896 until 1913. Courtesy Moosehead Historical Society

Visitors to the sporting camps relied on the steamers like the Katahdin, in service on Moosehead Lake from 1896 until 1913. Courtesy Moosehead Historical Society

There were four identifiable categories of sporting camps. First, classic camps were defined by their remote locations, distinctive log-built architecture, and lack of electricity. The more remote and spartan accommodations often offered greater hunting and fishing, and guests also could pursue outdoor sports like hiking, canoeing, and wildlife observation. Secondly, there were luxurious camps that were actually resorts, such as Moosehead Lake’s Mt. Kineo Hotel, which offered sporting vacations of complete comfort with many social events. A third, small, category of camps consisted of operations run out of remote houses and farms. The fourth category was composed of private hunting and fishing “clubs” whose membership and facilities were primarily for businessmen.

As conceptualized in popular travel literature, classic camps included a central dining lodge with surrounding cabins for the guests, owners, and guides. The cabins were spaced apart to afford some privacy, but they were close enough to create a small, self-contained community in the wilderness.

Camps had to be located near areas with wildlife and lake access, as many daily activities revolved around hunting and fishing. Prices for vacations started at several dollars per day and increased with the amount of luxury. Sports hired knowledgeable guides to escort them into the wilderness and to ensure their safety and success in these pursuits.

Classic camp operations often included a whole family, with proprietors’ wives planning and preparing the meals. The camps were generally too remote to regularly serve food items that the clients expected, and families worked their nearby farms to supply fresh vegetables and fruit, and tended chickens and domestic animals.

Camp proprietors and guides often built branch camps, too. These were small cabins a day away from the main camps, to enable sports to get to the best fishing and hunting locations.

The trains, steamboats, and stagecoaches of the Victorian era formed the transportation infrastructure that made travel to the wilderness possible, and this, in turn, led to the multiplication of camps.

Guests varied according to the time of year. The early spring and late fall months attracted a predominantly male clientele who devoted all their time to fishing (early spring) or to hunting (late fall). During the summer months, when the weather and travel were more agreeable, entire families came to vacation. With improvements in rail transportation, especially, the number of women increased during all seasons. Indeed, they were actively involved with hunting and fishing, both as guests and guides by the 1890s.

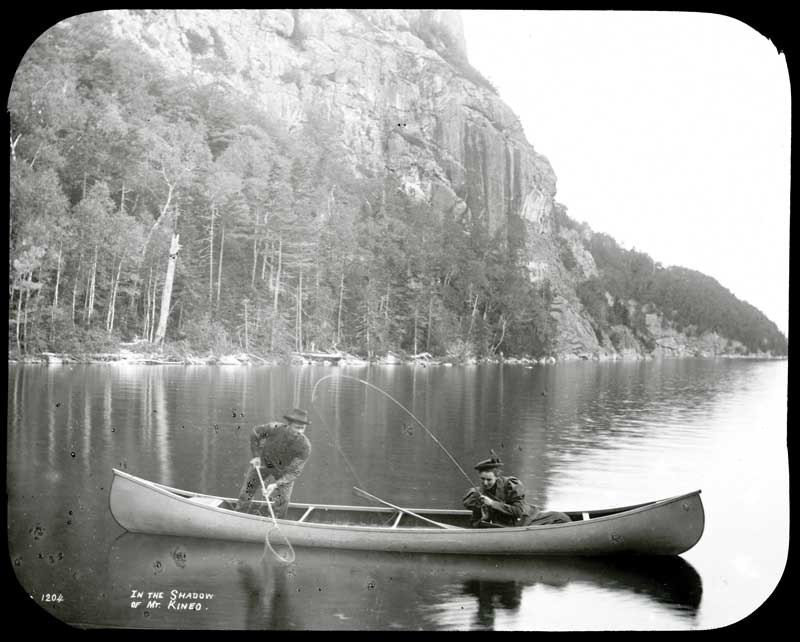

Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby, right, casts for fish with flies in the shadow of Mount Kineo, on Moosehead Lake. Collections of Maine Historical Society, courtesy of www.VintageMaineImages.com

Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby, right, casts for fish with flies in the shadow of Mount Kineo, on Moosehead Lake. Collections of Maine Historical Society, courtesy of www.VintageMaineImages.com

A pioneering woman guide, Maine native Cornelia T. Crosby (1854-1946), or “Fly Rod” as she was popularly known, once caught 200 trout on flies in a single day; she was also an early advocate of catch-and-release. She was the first woman to legally shoot a caribou in Maine. The love and focus of her writings were hunting and fishing in the north woods, and she worked tirelessly to promote the outdoors to sportsmen and their families.

The local newspaper in Fly Rod’s hometown of Phillips was the Phillips Phonograph, for which Crosby served as a part-time correspondent. By 1893, she was also writing for the national weekly Shooting and Fishing and was the subject of a glowing article in the Chicago Evening Post. As a travel writer for the Maine Central Railroad Company, Crosby contributed importantly through her popular outdoor column “Fly Rod’s Notebook”, which was published in Maine Woods magazine and appeared in many newspapers across the United States.

Her column typically contained commentary about the guides, owners, visitors, and fishing and hunting activity observed as she circulated among many camps. Crosby primarily focused on the Rangeley lakes area of western Maine, but also wrote of Moosehead Lake.

The publicity she generated in her position as a prominent female figure in turn-of-the-century New England, helped to attract thousands of would-be outdoorsmen—and women—to Maine’s camps. Her readers were typically wealthy sportsmen and their families who came for pleasure and relaxation.

In March 1897, the Maine legislature passed a bill requiring hunting guides to register with the state. Fly Rod was the first to be licensed of the 1,316 guides who registered that year.

Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby, pictured here in 1894, was a travel writer and the first licensed Maine Guide. Courtesy Collections of the Maine State Museum (69.23.1)

Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby, pictured here in 1894, was a travel writer and the first licensed Maine Guide. Courtesy Collections of the Maine State Museum (69.23.1)

Crosby once wrote, “I am a plain woman of uncertain age, standing 6 feet in my stockings. I scribble a bit for various sporting journals, and I would rather fish any day than go to heaven.”

The wives of sportsmen who fished, hunted, and vacationed in the Maine woods were encouraged by Crosby to come with their husbands. In 1915, she wrote in “Fly Rod’s Notebook,” “The wonderful skill which many women show with little practice with rod and rifle; the keen enjoyment they have in coming into our wilderness, where they always find good health awaits them; where they soon forget the gay society life for the real happiness, prove they make good companions. It used to be thought out-of-place for a woman to join a party going off with guides for a few days, or weeks, but now more parties have women than go without them.”

Crosby excelled at outdoors sports and was a role model to young women, bolstering a personal philosophy of athleticism and independence not often found in other women of her time.

Aside from her columns and work as a guide, Crosby gained a significant level of fame for her Maine sporting camp exhibit at the New York Sportsman’s Exposition in 1895 at Madison Square Garden, in which she displayed an authentic hunting camp including a small log cabin. That exposition was followed in future years with similar events in Boston and Philadelphia.

But there were other women extolling the benefits of nature as well. In the Pine-Tree Jungles. A handbook for sportsmen and campers in the Great North Woods, published in 1902, Mary Alden Hopkins wrote an article titled “Women in the Woods,” which was a publicity piece to attract women to the outdoors. In it she said, “In many a camp one will find a party of women, or group of schoolgirls with their teacher, who tramp and climb and fish under the guardianship of trustworthy Indian guides. A woman who has once experienced the freedom of such a vacation never willingly returns to a seaside hotel veranda. The number who distribute venison of their own shooting among friends at home is increasing each year, and not a few have a lordly moose to their credit. But if a woman does not care for hunting, she explores the wonderful lakes and streams in a canoe, or takes long tramps, from which she returns with an appetite which would appall any but an experienced camp cook. There are fish for the fisherwoman to catch, ferns and orchids for the botanist to classify, and invigorating air and glorious scenery for all to enjoy.… The Maine forest is a place where sick women grow well, and well women accumulate muscle and happiness; it is a sanitorium, playground, hunting and fishing ground all in one. The good effects of an outing here inevitably prove to be long and lasting, while the joys of the vacation are retained in sweetest memory for the rest of one’s life.”

Outdoorswoman Fannie Hardy Eckstorm (1865–1946) was an American writer, historian, and folklorist whose extensive personal knowledge of her native state of Maine secured her place as one of the foremost authorities on the history, wildlife, cultures, and lore of the region.

Eckstorm authored an article directed to husbands in the 1906 edition of In the Maine Woods titled “Take ‘Her’ with You.”

She wrote, “And yet there is little need today in camping in the Maine woods to overtax even a delicate woman. As for illnesses, unless one brings them with her, they do not come. She won’t get ill, not even by sleeping on boughs under a tent in hard fall rains, not even from wind and snow. Don’t fret about her health. You think she doesn’t care for this sort of life. It is an acquired taste, remember, even with yourself. She hesitates because she is not sure whether she will like it, and her not liking might spoil your whole outing. She fears she would be a burden; she thinks she might prevent your taking the long hard trip which you have been planning; she pre-supposes that if you are after large game you could not be bothered with a woman in the camp; in short, sir, she consults your imagined pleasure rather than her own.”

Another aspect of women’s roles at sporting camps was that of management, notes Maine historian William Geller. Between 1890 and 1910, as the number of “sports” increased, individual guides opened camps where they could stay. “By 1910, their camps could not survive on just men. The owners turned to their wives for their cooking, ingenuity, and organizational skills. Their love of the wilderness and their work matched that of their husbands. … This was a notable contrast to the rugged-male omnipresence at the birth of the sporting camp era.”

Though that particular era has passed, camp life and outdoor recreation continue to draw both visitors and those who choose to earn a living in Maine’s north woods and waterways.

✮

Roger Allen Moody lives in Camden and is a former Knox County commissioner and longtime municipal and school manager in Maine communities. This story is an edited excerpt from his latest book, Historic Sporting Camps of Moosehead Lake, Maine (North Country Press).

Roger Allen Moody lives in Camden and is a former Knox County commissioner and longtime municipal and school manager in Maine communities. This story is an edited excerpt from his latest book, Historic Sporting Camps of Moosehead Lake, Maine (North Country Press).