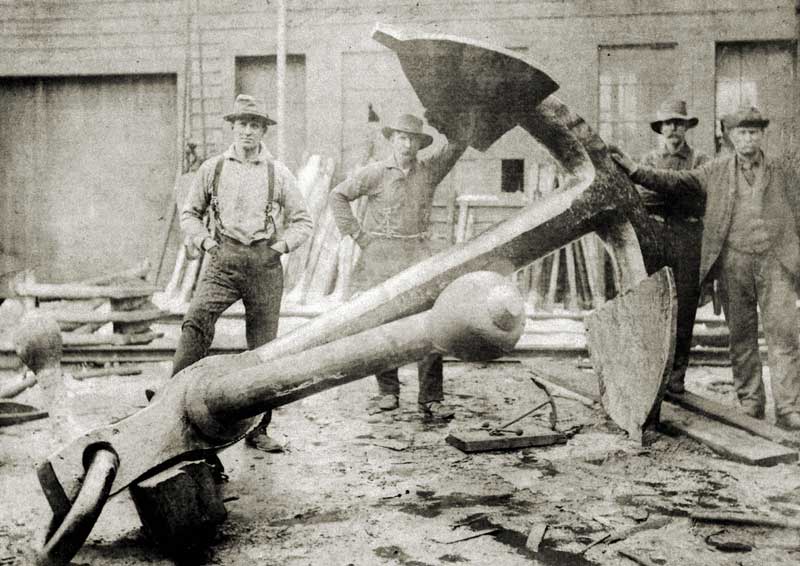

A crew at W.G. Alden’s Camden Anchor Works circa 1890 stands with a fixed-shaft anchor weighing 7,900 pounds. The anchor would likely have been used on a six-masted schooner. Note the small model anchor on the ground below. Image courtesy Walsh History Center, Camden Public Library

A crew at W.G. Alden’s Camden Anchor Works circa 1890 stands with a fixed-shaft anchor weighing 7,900 pounds. The anchor would likely have been used on a six-masted schooner. Note the small model anchor on the ground below. Image courtesy Walsh History Center, Camden Public Library

During the 1860s, river-run water from the 3½ mile-long Megunticook River in Camden, which drops 142 feet over its length, powered five woolen mills, two foundries, and a manufacturer of gunpowder for lime industry blasting. One of the foundries, located about one-half mile upstream from the harbor, was the Camden Anchor Works. Thousands of tons of cast-off iron were purchased annually from which to forge anchors, and the foundry’s blazing fires and ringing trip hammers were seen and heard for miles across Penobscot Bay. Brothers Horatio and William G. Alden began manufacturing anchors in 1866, and after Horatio’s death in 1877, William continued the business.

It grew to become the largest anchor manufacturing plant in the United States, employing up to 200 workers, and its anchors were carried on vessels throughout the world. The business was very prosperous until the late 1890s when the “stockless” anchor design replaced the “holding” anchor.

In 1901, Alden sold the business and facility to Maj. John Bird II of Rockland who merged it with his Rockland Machine Company to create the new Camden Anchor-Rockland Machine Company. The company built boats, launches, and dories, and manufactured the famous Knox one-cylinder gasoline engine. Known as a “one-lunger” and first built around 1901, it featured a large flywheel to carry the engine through to the next firing stroke in the cycle. The Knox engines created a distinctive sound on the Maine waterfront as their characteristic “bangbangbang” rang out from working harbors. These early engines, which ranged in size from 1½ to 7½ horsepower, have been credited with beginning the shift of the lobster fishing industry from sail to motor power.

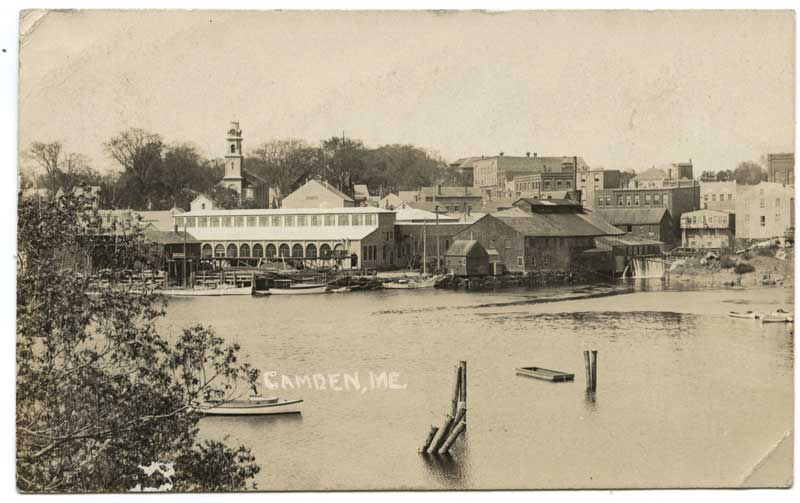

This postcard of Camden’s inner harbor shows the massive Camden Anchor-Rockland Machine Co. buildings on what is now Camden’s public landing. Betty Frost Postcard Collection, Walsh History Center, Camden Public Library

This postcard of Camden’s inner harbor shows the massive Camden Anchor-Rockland Machine Co. buildings on what is now Camden’s public landing. Betty Frost Postcard Collection, Walsh History Center, Camden Public Library

In February 1907, the Camden Anchor-Rockland Machine Company moved into a new building on Camden’s waterfront at the head of Camden’s inner harbor. An early boat order was for two peapods fitted with 3-hp Knox gasoline engines to go to Munich, Germany. Later a 39' vessel was built, transferred to a train in Rockland, and delivered to South Carolina. A variety of launches, yawl dories, and cabin cruisers were also constructed during the pre-WWI era.

The Great Northern Paper Company’s GNP Co. No. 3, a round-bottom workboat for log drives, was built in 1912. She was 37' LOA and was powered by a 4-cylinder, 4-cycle, 40-hp Knox gasoline engine.

The company continued to evolve, manufacturing the popular Knox engine with 2, 4, and 6 cylinders up to 75 horsepower. With the demand for larger boats came the construction of two launching ways to accommodate vessels up to 100 feet.

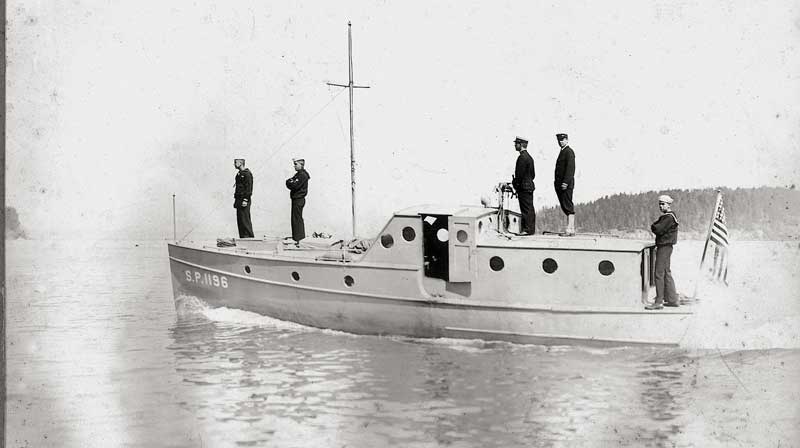

Camden Anchor-Rockland Machine Co. built the 34-foot wooden-hulled Wego as a private boat. The US Navy leased her from Buckminster Fuller’s family in 1917. Fuller, who later became known as an innovative architect, joined the Navy at the same time, and captained the Wego on sub-patrols. He is at the helm in this image. Image courtesy Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

Camden Anchor-Rockland Machine Co. built the 34-foot wooden-hulled Wego as a private boat. The US Navy leased her from Buckminster Fuller’s family in 1917. Fuller, who later became known as an innovative architect, joined the Navy at the same time, and captained the Wego on sub-patrols. He is at the helm in this image. Image courtesy Estate of R. Buckminster Fuller

The 34' Wego was built as a private wooden-hulled motorboat, and the U.S. Navy acquired her in 1917 under a free lease from her owner, Mrs. R. Buckminster Fuller of New York City and Bear Island in western Penobscot Bay. As the USS Wego (SP-1196), she served on local patrol duties in northern New England waters and was returned to the Fuller family in October 1918.

In 1914, the U.S. Navy ordered four battleship tenders of 35' LOA, 8' beam, and 5½ ton weight; their Sterling 6-cylinder engines gave a top speed of 15 knots (newspaper reports identify these first two tenders as C-215 and C-216.) Other WWI era vessels ordered included seven supply boats for the U.S. Coast Guard for use in Florida, five surf boats, and a 35' admiral’s barge. Four 110' submarine chasers (SC Class) were built at the yard: SC 251 commissioned in 1917, SC 252 in 1918, SC 407 and SC 408 in 1919.

The class of vessel known as the “subchaser” originated during World War I. Because steel was scarce, and the capacity of big shipbuilding yards was already dedicated to building destroyers and other large ships, Franklin D. Roosevelt (then a young Assistant Secretary of the Navy) sought designs for a subchaser made of wood that could be built quickly in small boatyards. Subchasers were 110' long with a 16' beam, and powered by three Standard 6-cylinder, 220-hp gasoline-driven engines. The SC-1 class subchaser had a displacement of 85 tons, top speed was 17 knots, and the cruising range was 1,000 miles. The armament consisted of two 3" guns (23-caliber) and two machine guns. Later a depth-charge projector was substituted for the aft 3" gun, and it proved to be the most effective antisubmarine weapon of all.

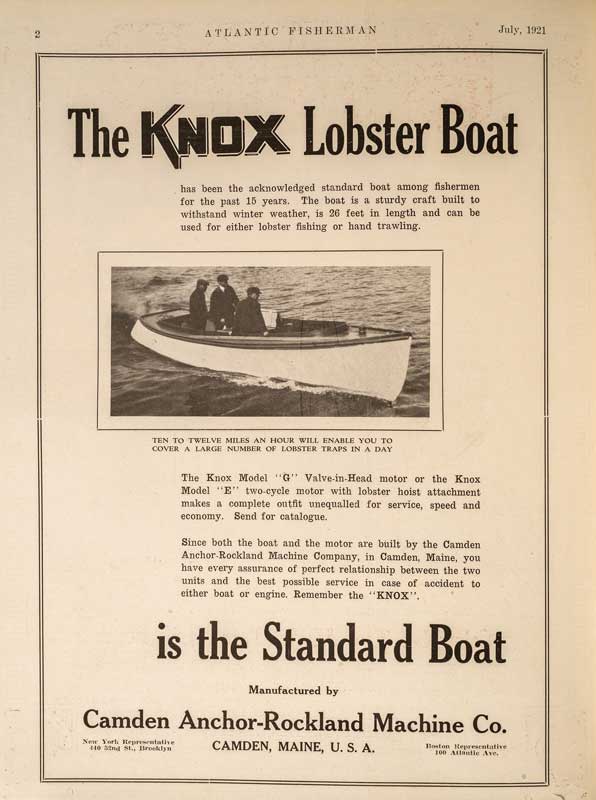

This ad for a 26-foot lobsterboat ran in Atlantic Fisherman in 1921. “Ten to twelve miles an hour will enable you to cover a large number of lobster traps in a day,” it reads. Atlantic Fisherman image courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum A total of 441 SC class subchasers were built for the war effort. Many were built by small yards in the United States because Navy yards were committed to building the steel destroyers and battleships. Other Maine yards known to have built SC Class subchasers were the Rice Brothers yard and the Hodgdon Bros. yard, both in East Boothbay.

This ad for a 26-foot lobsterboat ran in Atlantic Fisherman in 1921. “Ten to twelve miles an hour will enable you to cover a large number of lobster traps in a day,” it reads. Atlantic Fisherman image courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum A total of 441 SC class subchasers were built for the war effort. Many were built by small yards in the United States because Navy yards were committed to building the steel destroyers and battleships. Other Maine yards known to have built SC Class subchasers were the Rice Brothers yard and the Hodgdon Bros. yard, both in East Boothbay.

After WWI, local builders took the Navy launch designs and modified them to meet the summer cruising needs; and in the early 1920s, Camden Anchor Works-Rockland Machine Co. offered stock launches ranging from 25' to 35' to summer people and lobster fishermen alike.

A 34' cruiser was designed and built at the facility in 1921, and in 1923 three 31' fishing boats were constructed along with several pleasure and fishing boats in the 25' to 30' range. Also in 1923, there were 14 Alden O-class 18' knockabouts built for the Northeast Harbor Yacht Club.

A 45' luxury yacht and a schooner yacht were completed in 1924, but the company folded in 1925 due to competition from other engine makers.

A 1921 ad from Atlantic Fisherman magazine for Knox Motors. Atlantic Fisherman image courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum Isadore Gordon of Rockland purchased the buildings and property in September 1928 and founded the Camden Sardine Company. Angus W. Holmes of Stockton Springs was the company’s president and Angus M. Holmes was the treasurer and general manager. This new development did not go over well with many Camden residents who worried about the impact a cannery would have on their harbor. At about the same time, a state law had been passed granting municipalities authority to enact zoning ordinances to restrict “undesirable” enterprises. Camden Selectmen convened a special town meeting at which it was voted 290 to 213 to approve zoning restrictions that prohibited sardine or fish packing, glue manufacturing, fertilizer manufacturing, slaughtering, lime burning, and the manufacture of imitation pearls from fish scales from locations in Camden within a half-mile radius of the post office.

A 1921 ad from Atlantic Fisherman magazine for Knox Motors. Atlantic Fisherman image courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum Isadore Gordon of Rockland purchased the buildings and property in September 1928 and founded the Camden Sardine Company. Angus W. Holmes of Stockton Springs was the company’s president and Angus M. Holmes was the treasurer and general manager. This new development did not go over well with many Camden residents who worried about the impact a cannery would have on their harbor. At about the same time, a state law had been passed granting municipalities authority to enact zoning ordinances to restrict “undesirable” enterprises. Camden Selectmen convened a special town meeting at which it was voted 290 to 213 to approve zoning restrictions that prohibited sardine or fish packing, glue manufacturing, fertilizer manufacturing, slaughtering, lime burning, and the manufacture of imitation pearls from fish scales from locations in Camden within a half-mile radius of the post office.

It would appear that a lawsuit filed by Camden Sardine against this new ordinance was successful, however, because by September 1929 the Camden Sardine Company employed 41 people with a weekly payroll of $1,300, according to a report in the local newspaper. The Camden plant was the site of several small fires, one in 1930 and two in 1933, before it burned down completely in 1935. A 24-year-old man who apparently set the fire was committed by a judge to the State Hospital in Augusta. The site became today’s Camden Public Landing.

Roger Moody is a retired Maine municipal manager and county commissioner who writes about boats and boating history.

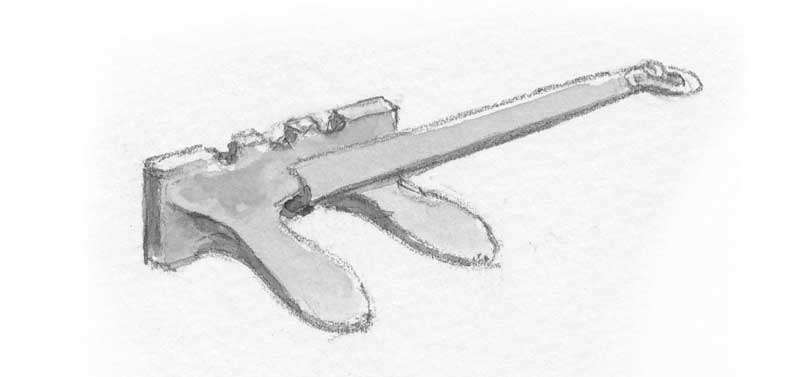

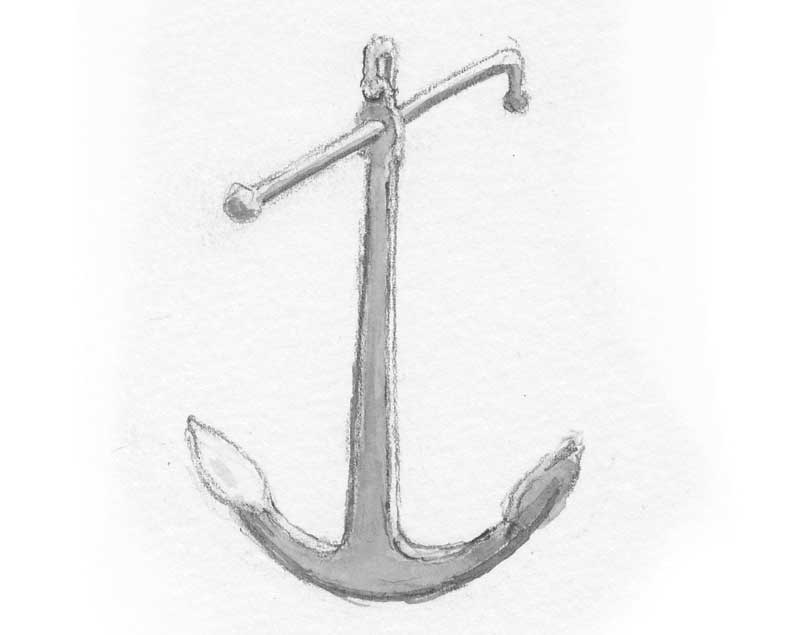

Stockless Anchor

Illustration by Ted WalshThe stockless anchor (above), patented in England in 1821, represented a significant development in anchor design. Stockless anchors consist of a set of heavy flukes connected by a pivot or ball-and-socket joint to a shank. Cast into the crown of the anchor is a set of tripping flukes that drag on the bottom, forcing the main flukes to dig in. Although their holding-power-to-weight ratio is significantly lower than a holding anchor with a fixed shaft (below), their ease of handling and stowage aboard large ships led to quick adoption. In contrast to the elaborate stowage procedures for the holding anchors, stockless anchors can be simply hauled up with the flukes against the hull or placed on a deck.

Illustration by Ted WalshThe stockless anchor (above), patented in England in 1821, represented a significant development in anchor design. Stockless anchors consist of a set of heavy flukes connected by a pivot or ball-and-socket joint to a shank. Cast into the crown of the anchor is a set of tripping flukes that drag on the bottom, forcing the main flukes to dig in. Although their holding-power-to-weight ratio is significantly lower than a holding anchor with a fixed shaft (below), their ease of handling and stowage aboard large ships led to quick adoption. In contrast to the elaborate stowage procedures for the holding anchors, stockless anchors can be simply hauled up with the flukes against the hull or placed on a deck.

Illustration by Ted Walsh

Illustration by Ted Walsh