All photos by Trish Romano

Mickey Finn, Black Ghost, Blacknose Dace: three classic streamers tied by the former owner of the North Country Angler fly shop, Bill Thompson.

Mickey Finn, Black Ghost, Blacknose Dace: three classic streamers tied by the former owner of the North Country Angler fly shop, Bill Thompson.

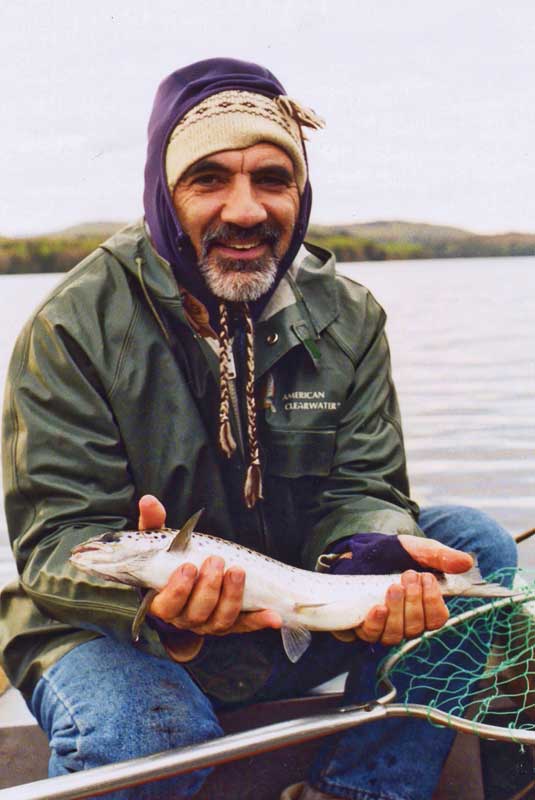

Most years, ice-out on Aziscohos Lake does not begin until sometime during the end of April. My wife and I open our cabin soon after the word has spread that the lake is once again clear. The weather can vary drastically during this time of year. There have been times when we’ve pulled into camp under blue skies, as the temperature climbed into the 70s. More often, we are greeted with overcast skies and nasty rain squalls, the type of harsh conditions favored by landlocked salmon and brook trout. Ravenous after a long winter of inactivity, these majestic fish can be found chasing schools of smelt throughout our lake.

Falling temperatures, overcast skies, and rain squalls are the type of weather conditions favored by Maine’s landlocked salmon. Shivering under layers of clothing, we pull our 15' 4" Grumman down to the shoreline, clamp the outboard to its stern, and prepare to troll traditional streamers meant to imitate smelts, the baitfish found throughout western Maine’s lakes, rivers, and streams.

Falling temperatures, overcast skies, and rain squalls are the type of weather conditions favored by Maine’s landlocked salmon. Shivering under layers of clothing, we pull our 15' 4" Grumman down to the shoreline, clamp the outboard to its stern, and prepare to troll traditional streamers meant to imitate smelts, the baitfish found throughout western Maine’s lakes, rivers, and streams.

Although we favor the Black Ghost, first tied by Herbert Welch in the 1920s, and the Gray Ghost, created by Carrie Stevens at about the same time, there are countless patterns from which to choose.

These days, Selene Dumaine, a renowned fly-tyer from Readfield, Maine, has gained a well-earned reputation as a result of her meticulous reproductions of Carrie Stevens’s streamers as well as her own innovative creations. Brett Damm, who guides out of the Rangeley Region Fly Shop, and Bill Thompson, the previous owner of the North Country Angler Fly Shop in North Conway, New Hampshire, are also masters at tying streamers sure to take fish while being trolled across a lake or pond anywhere in New England.

I prefer traditional patterns, but sometimes switch to modern streamers such as “The Sneeka” tied by Fern Bosse. Fern created many of his patterns on the banks of our lake, the reason perhaps, they never seem to fail.

Whether using old standards, new concoctions, or variations on these themes, trolling a streamer is one of the best ways to play tag with fish.

Although brook trout dive downward, wagging their heads like a dog with a bone, salmon tend to surge upward, sometimes exploding through the surface. I swear I can hear a salmon’s jubilant cry as it pirouettes across the waves, hook thrown skyward, the streamer suspended in mid-air as the fish falls back through the lake’s surface, the silver-and-black flash gone in an instant. The thrill, like spying the trail of a falling meteor, always produces oohs and ahs from spectators.

When we first moved into our camp, I purchased two fly rods from the local general store, each costing no more than a breakfast for two at MacDonald’s. I rigged the eight feet of fiberglass with equally inexpensive Medalist reels. Nearly 40 years later, Trish and I continue to troll with the same gear. When not in use, the rods hang across spruce notches nailed above the screens on the porch of our cabin.

Each reel houses 75 feet of floating line long past its usefulness for casting a dry fly, but quite adequate for trolling a streamer. I attach 35 feet of five-pound-test monofilament to act as a leader. Knotting the end of the monofilament to a swivel, I add another 10 or 12 feet of monofilament to the back of the swivel to serve as a tippet. The swivel prevents the streamer from twirling unnaturally in the wake of our boat’s motor.

Before the gasoline engine became popular, fishermen rowed a boat or paddled a canoe while trolling. This is still not a bad idea, and many times can provide more realistic action to a streamer. Like most anglers, I’ve become spoiled, relying upon an outboard to do the work for me. This time of year, I set the four-horsepower engine at its lowest speed as I cruise up one end of our cove and back down the other, our rods hanging out either side of the Grumman’s aluminum hull.

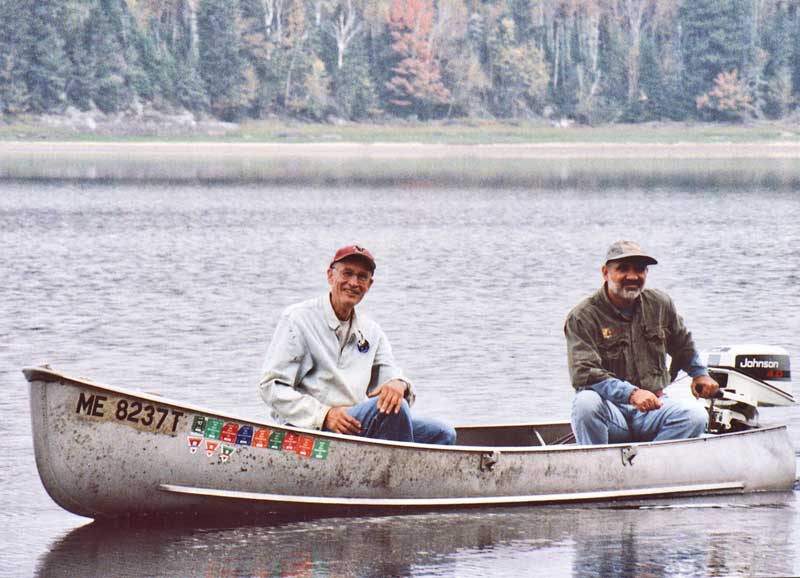

Robert Romano with his father-in-law, Charlie, heading out for day on the lake.

Robert Romano with his father-in-law, Charlie, heading out for day on the lake.

It is important to vary the speed of the engine as well as the direction of the boat. Some anglers troll parallel to shore while weaving to the left, then to the right, hoping to bring life to their streamers. Others will head out into the lake and then back again, turning the boat sharply as it approaches the shoreline. Either method can work. The trick is to use the speed and direction of the boat to impart action to the feathers and fur attached to the long-shanked hook while covering as much water as possible. This includes varying the depth of the streamer. Many times, a salmon will strike as the boat turns. This may be because the streamer has sunk deeper as the line bellows outward or because it has slipped over a ledge or stump where a fish is waiting. Either way, the movement of the boat has an effect on the streamer that is being pulled below the surface.

Pumping the rod every so often is a way to make the streamer appear injured or crippled, triggering the salmon’s instinct to strike. Trish swears by this method, and for this reason we do not use rod holders on our little boat.

Just after ice-out, salmon follow the smelt toward the surface. At this time, we let out 30 or more feet of floating fly line, allowing the leader and tippet to sink while working the streamer no more than a few feet below the surface.

As May slips into June, the water near the surface of the lake begins to warm. The smelt soon disperse as do the salmon, requiring a change in tactics. This time of year, many anglers use small sonar units to find the depth of the fish. They’ll add weight to their streamers or switch to metal lures and spoons, most popular of which are Mooselook Wobblers in different colors and Sutton 44s that are so effective, I once purchased an entire box of these copper spoons upon learning the company that manufactured them had gone out of business. (This was before the Internet and eBay.)

By August, both prey and predator have descended to the bottom of the lake where the water is cooler and more to their liking. Anglers with larger boats use downriggers to bring their streamers and spoons to the bottom. Some will switch to sewn bait. Those with smaller craft may use a fly line with a lead core to get down to the fish. These lead lines have a different color every 10 feet or so, allowing the angler to determine how much line is necessary to get to a desired depth. As two boats pass, it is not unusual for the occupant of one to call out, “How many colors?”

Unfortunately, the line’s lead interior significantly deadens the action once a fish is on the line. For this reason, I prefer to use a sinking line manufactured by the Cortland Company specifically for trolling. It is much lighter than the lightest lead line, and although it sinks a bit slower and requires more length to get the fly to the requisite depth, it is better able to transmit the action of the fish.

By fall, the surface temperature has once again cooled, bringing smelt and salmon back toward the surface and allowing us to switch back to our floating lines.

By summer, the lake’s brook trout have descended to the bottom where the water is cooler and more to their liking.

By summer, the lake’s brook trout have descended to the bottom where the water is cooler and more to their liking.

I string my fly lines on four spools—two sinking and two floating. When unsure of the salmon’s depth, I let out floating line while Trish trolls with the sinking line. If either of us takes a fish, the other can switch spools, letting out the necessary length of line to get to the proper depth. When doing so, I’ll clip the monofilament in front of the swivel, remove the spool from the reel, and replace it with the other, thereafter attaching the monofilament from the new spool to the swivel that continues to hold the streamer knotted to the end of the tippet. The entire process takes only a few minutes to complete.

Although Trish’s father is gone and her mother is now too old to travel long distances, for many years they would accompany us to camp. I remember August mornings when her father and I would motor down to the Ledges. Reputed to be the deepest part of the lake, the channel of the Magalloway’s streambed lies 70 feet under the surface there. I’d be in the Grumman’s stern, holding the arm of the little Johnson outboard. From where he sat in the bow, Charlie would stare into the thick fog. From somewhere in the gloom a loon might cry out, another returning its eerie call.

As we sliced through the stillness, the lake would slowly awaken, the few remaining wisps of fog swirling across its surface. Fast moving cumulus clouds would pass over the rising sun, forming shadows over the surrounding hills while a pleasant breeze slipped across the lake’s surface creating what Charlie called a “salmon ripple.” Under the drone of the outboard, our muscles would relax, tensions fade. Lost in the moment, there was no need to speak.

Lowering our sinking lines until the streamers bumped along the lake’s bottom, we slipped over the Ledges. We’d troll a pattern of my own design, which I call Summer Smelt—it’s a jumble of purple-and-black bucktail wrapped in silver tinsel. During the morning we might switch to a Mickey Finn, maybe a Black-nosed Dace, or perhaps one of Fern Bosse’s many steamers.

And so, the seconds would pass into minutes and the minutes into hours.

Eventually, Charlie would stretch his legs and I’d point the bow in the direction of our camp. If we were lucky, Trish would be picking blueberries for her mother to sprinkle into the pancake batter she’d be spooning onto the griddle as we walked back up the trail to our cabin.

Robert J. Romano Jr.’s most recent book is River Flowers, a collection of short stories and fishing tales set in the North Woods of Maine. Visit his website forgottentrout.com for more information.

Those interested in reading more about trolling with streamers should read Trolling Flies for Trout and Salmon by Dick Stewart and Bob Leeman. Although out of print for many years, this little treatise is now readily available. Another book that may be of interest is Tandem Streamers: The Essential Guide by Donald A. Wilson.