Douglas Coffin and his daughter Sigrid Coffin specialize in hand-cutting letters into stone for memorials and headstones. They are among about two dozen stone letter carvers in the country. Most lettering in stone these days is done by sandblasting.

Douglas Coffin and his daughter Sigrid Coffin specialize in hand-cutting letters into stone for memorials and headstones. They are among about two dozen stone letter carvers in the country. Most lettering in stone these days is done by sandblasting.

Photos by Lynn Karlin

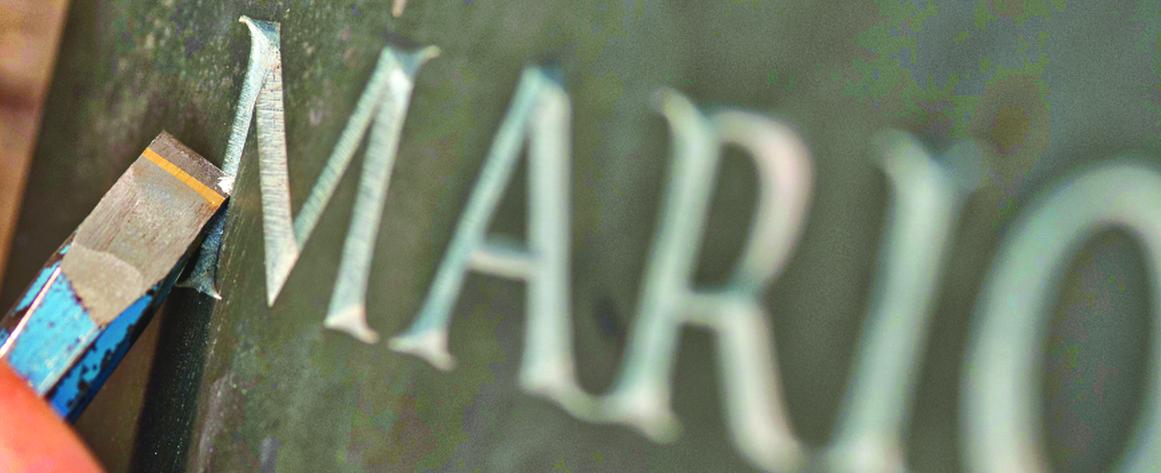

With one hand securing a chisel, and another wielding a brass hammer, Douglas Coffin and his daughter Sigrid spend their days focused on immortality. Or as close to immortality as most of us will get. As letter carvers, the bulk of the work of the father-daughter team of Douglas M. Coffin Lettercutter is creating headstones—beautiful, hand-carved life markers with letters that flow into each other, creating words that call out to be read. They consider their work to be among the most caring of human endeavors.  The Coffins stand while doing their carving and chisel each letter slowly, working from the inside out, one stroke at a time, starting with the first stroke which goes up the letter’s center.

The Coffins stand while doing their carving and chisel each letter slowly, working from the inside out, one stroke at a time, starting with the first stroke which goes up the letter’s center.

Douglas has been cutting letters into stone for 26 years; daughter Sigrid, a calligrapher, joined him four years ago. With only some two dozen stone letter carvers in the nation and no other women carving fulltime, they are a select pair.

Based now in Belfast, Douglas was born in Lewiston, the son of the late Judge Frank M. Coffin, who served on the U.S. Court of Appeals and briefly as the Congressional representative from Maine’s second district. Douglas was 40, working as an advertising creative director in Pennsylvania and finding it unsatisfying, when he happened to hear a lecture about letter carving. “I could do this,” he realized. He loved typography, understood two-dimensional design, was comfortable with tools, worked easily with clients—and was longing for a business that might thrive in Maine. He plunged in.

While gravestones are the bulk of the work, the Coffins also get calls to go big and high, carving, for example, the name of Pettengill Hall on the exterior of the Bates College building in Lewiston, and both names and inspirational words on the offices of Combined Jewish Philanthropies in Boston. Douglas spent most of last July chiseling donor names on a wall of the Hall of Nations inside the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. They’ve also worked on churches and public markers. But father and daughter are most fond of the stones that now appear in cemeteries from Maine’s Great Spruce Island to Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and beyond to Florida and California.

Sigrid described 16 small marble headstones in a long row at the back of a Hallowell cemetery. Each stone bears the name of a girl, along with her age, date of death, and the place: The Industrial School for Girls. Seeing it, said Sigrid, “the wind was knocked out of me—these darling little angels. From that simple information you can deduce that they were all orphans.”

She learned about the stones from a client whose dying wife had asked to join this line of girls. “I feel sometimes I could belong to them,” the woman told her. And so Sigrid created a headstone that was a bit larger, but made from the same marble, replicating the border of the smaller stones. “It was a shard of meaning that gave her comfort,” Douglas reflected.

"It’s still thrilling to carve a letter,” Douglas Coffin said. “You’re not carving an image of something, a representation, you’re carving the thing. In stone it’s particularly exciting; there’s an authority to stone that is really unmatched by any other substance.”

"It’s still thrilling to carve a letter,” Douglas Coffin said. “You’re not carving an image of something, a representation, you’re carving the thing. In stone it’s particularly exciting; there’s an authority to stone that is really unmatched by any other substance.”

Gravestones are stories, brief, highly symbolic ones. The medium enhances the message. Douglas recalled a conversation he had with a woman requesting a stone for her husband. She wanted both “In Loving Memory” and “Beloved Husband” to appear on the stone. “Why don’t you just say ‘my husband’,” suggested Douglas. “This little word ‘my’ is so fleeting, but when carved in stone it becomes so dear, so expressive.”

Most modern headstones are not carved by hand; they’re sandblasted. Typically, explained Douglas, the letters are machine-cut into a rubber stencil that’s placed on polished granite. Silica sand under high pressure is then blasted onto the stone, cutting out the words. The result is not as sharp, he said, and there’s no variation in spacing. So “LAMB,” for instance, would have a gaping hole between the “L” and the “A” as compared to the space between the “M” and the “B.”

To eyes trained in calligraphy or typography, poor spacing is as dissonant as an untuned instrument is to an ear trained in music. Father and daughter understand this. They wax eloquent about letters, about the relationship of letters within a word, about the possibility of a flourish beneath a “y.” It’s the art in this craft. “You want to have your letters as if you dipped into bucket of paint and went whoosh, all in balance,” said Douglas.

The carving is done gradually, from the inside out, one chisel stroke at a time, usually while standing. Once the design is sketched on the stone, the first chisel pass goes right up the letter’s center. This begins the trench. The second pass smoothes out the first, and the carver repeats, angling the chisel to one side, then the other, “chasing” the letter so it grows wider and deeper, until the v-cut has erased the letter sketched onto the stone, and the carver is satisfied with the elegance of the line.

Depending on the size and the letter—it’s much easier to chisel an “i” than a “w”—Douglas and Sigrid average two to three letters an hour. But the twelve-inch letters that Douglas carved on the exterior of Koelbel Hall at the University of Colorado Boulder were done at the rate of two letters a day. Yes, it does cost more to have a gravestone hand lettered. But the effort lives on, literally for centuries.

While their hands are busy chiseling beautiful letters, father and daughter have hours to contemplate the meaning of the words their letters form. “You can only carve great or loving words,” said Douglas. For that reason, he has a dream of teaching five Palestinians and five Israelis to hand letter in both Hebrew and Arabic, and have them each carve a plaque. “You can’t carve words of hate in stone,” he said.

Donna Gold writes from a century-old shingle home overlooking Penobscot Bay. She is the editor of COA, College of the Atlantic’s magazine.