The Multifaceted Creativity of Daniel Minter

In Atlantic Crossing Daniel Minter evokes Mother Ocean and the Middle Passage. Acrylic on wood panel, 30 by 24 inches. Image courtesy Daniel Minter

In Daniel Minter’s painting Atlantic Crossing, a Black woman stands chest-deep in the ocean, a broad skirt-like skein of circular shapes interspersed with bubbles radiating from her across the water. In the distance you can just make out a two-masted brig sailing into the sunset.

In Atlantic Crossing Daniel Minter evokes Mother Ocean and the Middle Passage. Acrylic on wood panel, 30 by 24 inches. Image courtesy Daniel Minter

In Daniel Minter’s painting Atlantic Crossing, a Black woman stands chest-deep in the ocean, a broad skirt-like skein of circular shapes interspersed with bubbles radiating from her across the water. In the distance you can just make out a two-masted brig sailing into the sunset.

The painting draws on the story of the Ibo slaves from Nigeria who, arriving on the shores of Georgia in 1803, decided that suicide was preferable to enslavement. After leaving the ship, the captives turned around and entered the sea. Minter offers three iterations of the story of what happened next, as handed down through generations: They walked across the water, they walked underneath the water, or they flew back to Africa.

The figure in the painting, Minter explained, is Mother Ocean, who “watches over all of our children and is the source of all of us—she births us and accepts us back.” The far-off ship is the slaver that brought the men and women from Africa, through the Middle Passage.

Versions of that vessel appear in a number of Minter’s pieces. For an installation at Lynden’s Sculpture Garden in Milwaukee, he created a cross-section of the ship in which tin cans set in rows represent “the commodification and the movement of product across the ocean”—the product being slaves. The boat also appears in his Water Road series.

The forced removal of Malaga Island residents in 1912 haunts Minter and has inspired many powerful paintings, including Method II, acrylic on canvas, 60 by 20 inches. Image courtesy Daniel Minter

The Portland-based artist brings empathy to his vision of history and the world, whether through his paintings and sculptures or his award-winning illustrations for children’s books. He shares his vision as a professor at the Maine College of Art and Design and as a mentor at the Indigo Arts Alliance, a residency program dedicated to cultivating the development of artists of African descent.

The forced removal of Malaga Island residents in 1912 haunts Minter and has inspired many powerful paintings, including Method II, acrylic on canvas, 60 by 20 inches. Image courtesy Daniel Minter

The Portland-based artist brings empathy to his vision of history and the world, whether through his paintings and sculptures or his award-winning illustrations for children’s books. He shares his vision as a professor at the Maine College of Art and Design and as a mentor at the Indigo Arts Alliance, a residency program dedicated to cultivating the development of artists of African descent.

Minter started incorporating boats in his work after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Seeking the source of the abandonment of Blacks in New Orleans, he kept returning to the transatlantic slave trade, “that idea that our bodies belonged to others, that they were brought over here as property, in that boat.” The slave ship burdens all Americans “because so many things in this country are based on the exchange of currency and when this country was formed, our bodies were that currency. And that’s what that boat represents.”

The prow of another boat appears in what is perhaps Minter’s best-known body of work, paintings related to the removal of an interracial community on Malaga Island off Phippsburg in 1912—among the most shameful incidents of racial injustice in Maine’s history. The 47 men, women, and children who lived by fishing, taking in laundry from the mainland, and other work were evicted from their island home, eight of them committed to the Maine School for the Feeble-Minded. The removal was total: Even the dead were exhumed and relocated.

In Minter’s painting Method II, a dark boat hovers over a pair of calipers, which in turn reach downward toward the dark island. This instrument for measuring skulls was used by advocates of eugenics, a racist theory that played a significant role in Maine’s decision to remove the islanders and institutionalize several of them.

Minter first heard about Malaga Island when he was working with social justice champion Rachel Talbot Ross on the Portland Freedom Trail, a project to recognize important sites in African American history. He felt there should be an acknowledgment that the community had existed, so he created art that he hoped would help him and others understand the story—“some simple images that could hold the emotion of loss and strength at the same time.”

In a series of paintings and mixed media pieces, as well as through community activities, Minter has brought the islanders back to life. He took part in archaeological digs on Malaga and designed an information kiosk for visitors to the island. His paintings, profound in their emotional and visual power, honor the dead. His approach is archetypal: the figures and their adornments stand in for the lost and forgotten, yet they were inspired by Malaga residents.

Minter notes that what happened in Maine was no isolated incident, but rather part of post-Reconstruction America when Black people began to incorporate themselves into

society. Their efforts to create communities caused a vicious backlash. Places like Malaga Island and the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma, were targeted, and many were wiped out or “embargoed out of existence.”

Minter said he likely will always be responding to the Malaga story in his work. He is haunted by the islanders’ fate.

Daniel Minter, photograph by Séan Alonzo Harris.

Minter was born in rural Ellaville, in south Georgia, in 1961, the ninth of 12 children. He drew inspiration from his mother who took care of his family but also of the community at large. “She embodied that energy of nurturing,” he said.

Daniel Minter, photograph by Séan Alonzo Harris.

Minter was born in rural Ellaville, in south Georgia, in 1961, the ninth of 12 children. He drew inspiration from his mother who took care of his family but also of the community at large. “She embodied that energy of nurturing,” he said.

After earning an Associate in Arts degree in visual communications from the Art Institute of Atlanta, Minter worked as an illustrator and computer graphic artist for several years. He eventually left the corporate world to pursue painting and sculpture.

In 1992 at age 31 he moved to Seattle, his first time living outside his home state. It was a culture shock for the artist. Needing “pieces of home,” he made a bottle tree, a traditional southern way to capture evil spirits. In his case, he said he used it to “hold ancestral spirits near me, to keep me company.”

In a remarkable TEDxDirigo talk, “Fish and Brooms: Art, Personal Icons, and Human Connection,” in 2012, Minter discussed the cultural significance of elements of his culture growing up, and encouraged his audience to look deeply at its own personal icons and symbols. “If you don’t know what they are, look to your mother. Look to your grandmother. I’m sure there’s something she must have touched that shows you a part of her—and a part of her that’s in you.” And then he offered this caution: “If you don’t know what your personal symbols and icons are, or if you don’t make an effort to look and find what they are, there are many corporations that are deeply engaged in manufacturing culture, icons, and symbols for you. And they do not care about your grandmother.”

The tin cans in Minter’s Commerce Vessel represent slaves as commodities shipped around the world. Wood, metal, found objects, 4 by 5½ feet. Image courtesy Daniel Minter

The tin cans in Minter’s Commerce Vessel represent slaves as commodities shipped around the world. Wood, metal, found objects, 4 by 5½ feet. Image courtesy Daniel Minter

Minter lived for a time in Chicago and Brooklyn, and spent time in Brazil in 1994 on a travel grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Over the years he taught at a variety of institutions, most recently Colby College’s Lunder Institute, Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, Monson Arts, and Williams College.

Minter has taught at the Maine College of Art and Design since 2008; the college gave him an honorary Doctorate of Arts degree in 2019. “I teach there as a way of being a part of the creative community in Portland and as a way of sharing the things that I value, the things that I use, the way that I work, and the way that I think about the work,” he said. He is also a board member of the Illustration Institute on Peaks Island, an organization that, in his words, “cultivates and takes advantage of the strong community of illustrators we have here in Maine.”

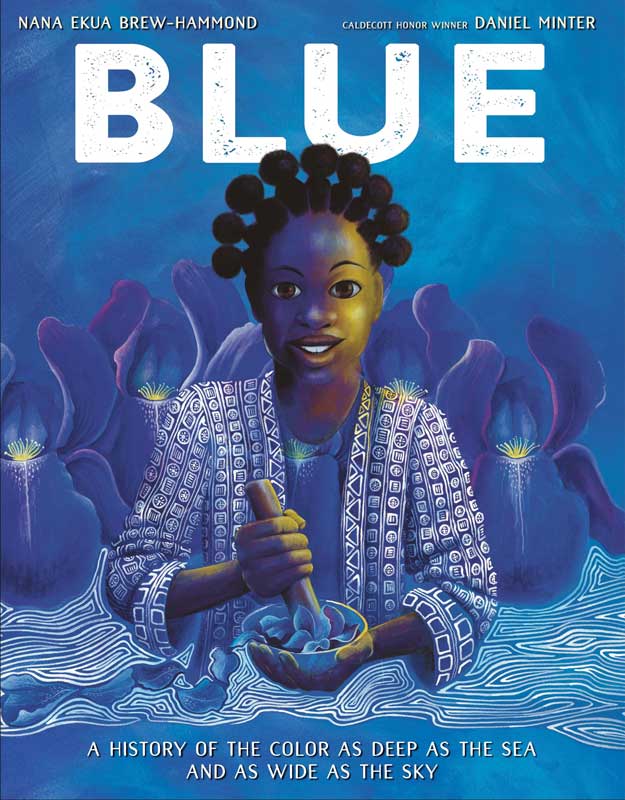

Minter entered the children’s book field in 1994, when the author Evelyn Coleman recommended him to illustrate her book The Foot Warmer and the Crow, published by Macmillan. He went on to illustrate a dozen more books, including Kelly Starling Lyons’s Going Down Home with Daddy, which took home a 2020 Caldecott Honor award and the same author’s Ellen’s Broom, winner of a Coretta Scott King Illustration Honor in 2013. Minter’s latest book, coming out in February, is Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond’s Blue: A History of the Color as Deep as the Sea and as Wide as the Sky.

In 2003 he and his wife Marcia moved to Portland. Marcia became vice president and creative director at L.L. Bean, while Daniel undertook illustration projects and taught. In 2004 and 2011 he was commissioned to create Kwanzaa stamps for the U.S. Postal Service.

The latest book by the award-winning illustrator Daniel Minter: Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond’s Blue: A History of the Color as Deep as the Sea and as Wide as the Sky. Image courtesy Daniel Minter

In 2019, the couple launched the nonprofit Indigo Arts Alliance in the city’s East Bayside neighborhood. The 4,000-square-foot building features flexible workspace, plus two studios, one for a visiting artist, the other for Minter, who has mentored some of the artists in residence. “Mentorships are a huge part of our philosophy and our reason for being—they’re important to anyone who is going into a profession or craft or discipline,” he said. At the time of this interview, Minter was looking forward to getting to know the Alliance’s fall resident, Maine-based Brazilian-born mime and storyteller Antonio Rocha.

The latest book by the award-winning illustrator Daniel Minter: Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond’s Blue: A History of the Color as Deep as the Sea and as Wide as the Sky. Image courtesy Daniel Minter

In 2019, the couple launched the nonprofit Indigo Arts Alliance in the city’s East Bayside neighborhood. The 4,000-square-foot building features flexible workspace, plus two studios, one for a visiting artist, the other for Minter, who has mentored some of the artists in residence. “Mentorships are a huge part of our philosophy and our reason for being—they’re important to anyone who is going into a profession or craft or discipline,” he said. At the time of this interview, Minter was looking forward to getting to know the Alliance’s fall resident, Maine-based Brazilian-born mime and storyteller Antonio Rocha.

In the coming months, Minter will be focused on a collaboration with Brazilian artist Eneida Sanches, Indigo Arts Alliance’s first artist in residence. Originally scheduled for this January at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockland, their show was pushed back to October 2022 due to Covid.

The Alliance teamed up with acclaimed children’s book author and illustrator Ashley Bryan in 2020 to present the Beautiful Blackbird Children’s Book Festival in Portland, which returned in a virtual format this past August. Named for one of Bryan’s most beloved children’s books, the festival celebrates Black authors and illustrators.

This past July, Minter delivered the inaugural Ashley Bryan Honorary Lecture at the Jesup Library in Bar Harbor. He has noted how growing up he could never have imagined someone like Bryan or the late artist David Driskell existed. “I am endlessly thankful for the path and the doors they opened for me,” he said, adding that he aspired “to be as open, to be as giving” as these two friends.

✮

Carl Little’s most recent book is Mary Alice Treworgy: A Maine Painter (Marshall Wilkes). The Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation gave him a Lifetime Achievement Award for his art writing in 2021.

You can learn more about Minter at www.danielminter.net. He is represented by

Greenhut Galleries in Portland and the Spillman-Blackwell Gallery in New Orleans.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.