Rangeley Lakes Camps

How fishing started a Tourist Mecca

The Oquossoc Angling Association’s Camp compound at Indian Rock, at the confluence of the Kennebago and Rangeley rivers, was founded in 1868 by New York stock broker George Page and several of his New York friends. It was one of the first sporting camps established in the Rangeley Lakes region. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

The Oquossoc Angling Association’s Camp compound at Indian Rock, at the confluence of the Kennebago and Rangeley rivers, was founded in 1868 by New York stock broker George Page and several of his New York friends. It was one of the first sporting camps established in the Rangeley Lakes region. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Many parts of New England were more populated a century or more ago, and much of the countryside was more cultivated and tamed than it is today. The Rangeley Lakes region, which over the past 150 years has hosted tourists and fishermen at more than 100 hotels and commercial camps, is one of these places.

The resort hotels are gone today, with a few exceptions; the lawns and manicured grounds surrounding the lakes have almost entirely returned to forest. Many of the camps survive, some as group-owned associations, but most are in private ownership. A number of the hotel cottages still stand as well, also in private hands. The rustic style also remains, as does the communal nature of camp life, although generally on a smaller, familial scale.

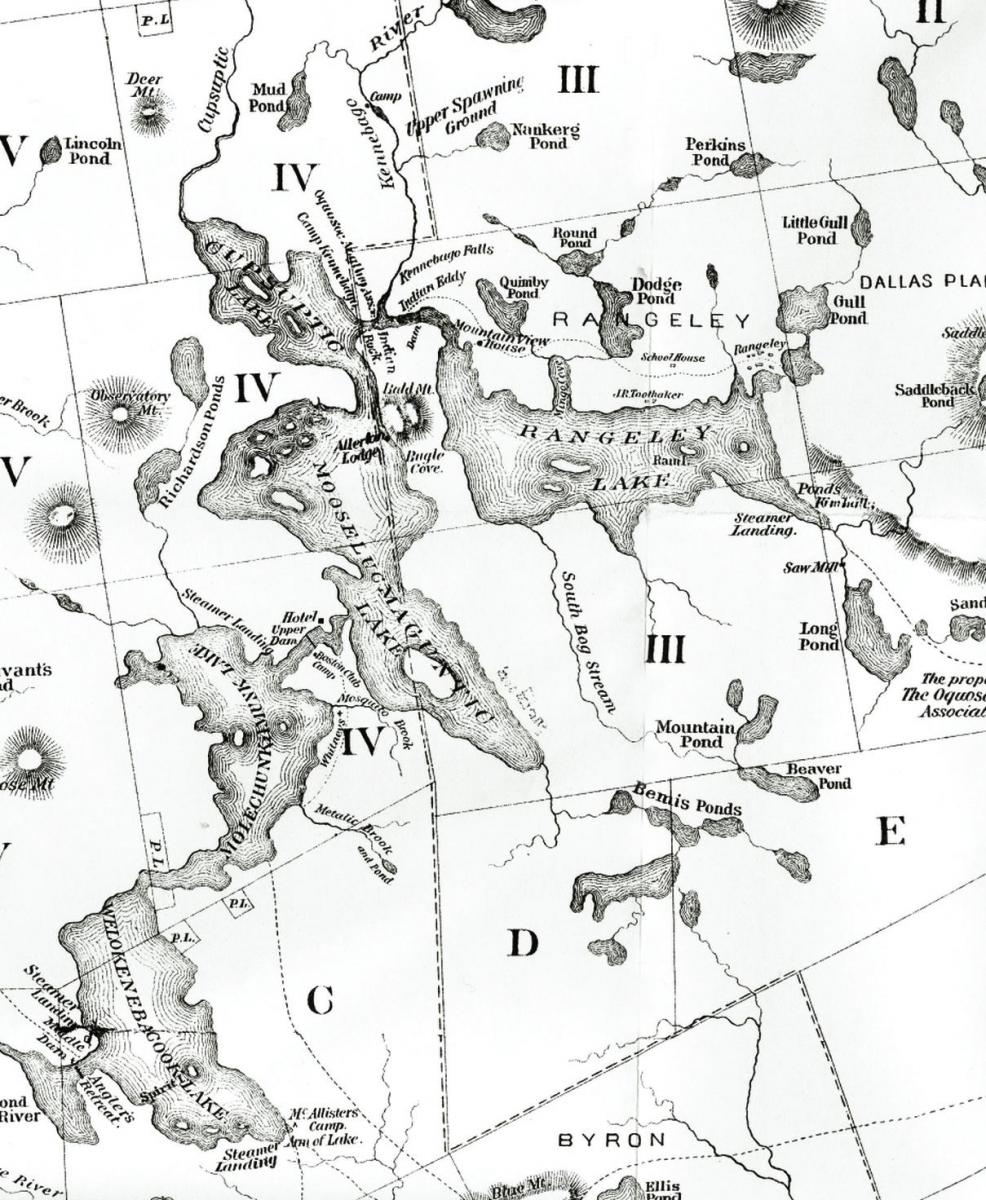

Section of an 1876 map of Rangeley by Charles A. Farrar. He wrote some of the earliest guides to the Rangeley Lakes, where his commercial enterprises included hotels and much of the region’s transportation infrastructure. Map courtesy Bethel Historical Society

In 1796, James Rangeley, in company with three other men, bought 30,000 acres at the headwaters of the Androscoggin River from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. But Rangeley and his company never occupied their lands, and the lakes remained in the possession of their ancestral occupants, the Abenaki Indians, for another two decades.

Section of an 1876 map of Rangeley by Charles A. Farrar. He wrote some of the earliest guides to the Rangeley Lakes, where his commercial enterprises included hotels and much of the region’s transportation infrastructure. Map courtesy Bethel Historical Society

In 1796, James Rangeley, in company with three other men, bought 30,000 acres at the headwaters of the Androscoggin River from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. But Rangeley and his company never occupied their lands, and the lakes remained in the possession of their ancestral occupants, the Abenaki Indians, for another two decades.

The first European settlers arrived in 1816 or 1817, when Luther Hoar, accompanied by his wife and eight children, left their former home in Madrid, Maine, and arrived at the lake settlement on the eastern shore of what is now Rangeley Lake. In the next few years the Hoars were joined by several other families, including those of John Toothaker and David Quimby. These names can be found today not only attached to places, such as Toothaker Island, but also among the area’s present residents, the descendants of the original settlers. Rangeley never saw his land, but his son, James Rangeley, Jr., inherited his father’s share and later bought out the other three partners. In 1825 he moved his family onto the land with plans to build a community and economy based on agriculture, lumber, and mining. The younger Rangeley’s discovery of Hoar’s settlement on his land, already established as a modest community engaged in farming and logging, fit his ambitions nicely. Rather than eject the squatters, Rangeley adapted his plan to their presence.

These four choice brook trout were caught at the Oquossoc Angling Association’s Camp Kennebago in the early 1900s and immortalized on a postcard. Photos courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

These four choice brook trout were caught at the Oquossoc Angling Association’s Camp Kennebago in the early 1900s and immortalized on a postcard. Photos courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Five big lakes and a constellation of smaller lakes and ponds form the headwaters of the Androscoggin, which rise in a high plateau close up against the crest of the northern Appalachians. Two of the big lakes still bear their original Indian names, Mooselookmeguntic and Cupsuptic, but the three others, Oquossoc, Mollychunkamunk, and Welokennabacook, are now better known as Rangeley, Upper Richardson, and Lower Richardson. The big lakes had been rich hunting and fishing grounds for the Abenaki for generations, and the new settlers quickly discovered that fish, especially brook trout, thrived in the clear, cold lake waters.

A guide rows an iconic Rangeley boat while his “sport” in the stern fishes at Grant’s Camps on Kennebago Lake. Grant’s is still open for business today. Courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Despite its remoteness, by the 1840s a few sportfishermen were coming from Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York to explore the lakes. By this time the “Lake Settlement” on Oquossoc Lake was known as the town of Rangeley and had grown to 39 families. Logging was also on the rise, with the Androscoggin River filled with logs destined for sawmills downstream. The river itself was beginning its long career as one of New England’s industrial arteries. One of the first stages in that evolution was the construction in 1850 of the Upper Dam at the western end of Mooselookmeguntic Lake. This dam was used to raise the lake water levels, linking it to Cupsuptic Lake and facilitating the movement of logs. As a side benefit, the dam created pools and spillways, which made especially good fish habitats and increased the sportfishing potential of the place even further.

A guide rows an iconic Rangeley boat while his “sport” in the stern fishes at Grant’s Camps on Kennebago Lake. Grant’s is still open for business today. Courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Despite its remoteness, by the 1840s a few sportfishermen were coming from Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York to explore the lakes. By this time the “Lake Settlement” on Oquossoc Lake was known as the town of Rangeley and had grown to 39 families. Logging was also on the rise, with the Androscoggin River filled with logs destined for sawmills downstream. The river itself was beginning its long career as one of New England’s industrial arteries. One of the first stages in that evolution was the construction in 1850 of the Upper Dam at the western end of Mooselookmeguntic Lake. This dam was used to raise the lake water levels, linking it to Cupsuptic Lake and facilitating the movement of logs. As a side benefit, the dam created pools and spillways, which made especially good fish habitats and increased the sportfishing potential of the place even further.

The Oquossoc Angling Association’s main building, shown here in the 1870s, contained sleeping quarters, a kitchen, dining room and general sitting room. Courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission

When Henry O. Stanley (Maine’s fisheries commissioner after 1883) and New Yorker George S. Page visited Rangeley in 1860 to investigate rumors of good fishing, they found large and abundant brook trout. Page returned to New York with eight trout, ranging between five and eight pounds, packed in sawdust and ice. Their adventure drew public attention to the Rangeley Lakes, but their report of the quality and size of the fish was met with some incredulity by sportsmen back in the city. Skeptics were satisfied only after Harvard naturalist Louis Agassiz inspected Page’s catch and confirmed that the fish were indeed brook trout and not lake trout or some other less desirable species.

The Oquossoc Angling Association’s main building, shown here in the 1870s, contained sleeping quarters, a kitchen, dining room and general sitting room. Courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission

When Henry O. Stanley (Maine’s fisheries commissioner after 1883) and New Yorker George S. Page visited Rangeley in 1860 to investigate rumors of good fishing, they found large and abundant brook trout. Page returned to New York with eight trout, ranging between five and eight pounds, packed in sawdust and ice. Their adventure drew public attention to the Rangeley Lakes, but their report of the quality and size of the fish was met with some incredulity by sportsmen back in the city. Skeptics were satisfied only after Harvard naturalist Louis Agassiz inspected Page’s catch and confirmed that the fish were indeed brook trout and not lake trout or some other less desirable species.

The main building looks much the same today. The camp is now owned by a private association. Photo by W. Tad Pfeffer

Fish—not just plentiful fish but big fish, with trophy potential—started to make Rangeley famous at roughly the same time that the recreational potential of the Adirondack Mountains was attracting notice. The quality of sportfishing in the Rangeley region compared favorably with that in the Adirondacks, and soon local residents began to supplement farming and logging with the more profitable, easier, and probably more fun occupation of guiding.

The main building looks much the same today. The camp is now owned by a private association. Photo by W. Tad Pfeffer

Fish—not just plentiful fish but big fish, with trophy potential—started to make Rangeley famous at roughly the same time that the recreational potential of the Adirondack Mountains was attracting notice. The quality of sportfishing in the Rangeley region compared favorably with that in the Adirondacks, and soon local residents began to supplement farming and logging with the more profitable, easier, and probably more fun occupation of guiding.

From the 1870s on, Rangeley built its fortunes around recreational fishing. Guidebooks described the geography of the lakes and mountains, gave advice on securing guide services, and provided details on transportation by rail, road, and steamboat, as well as on accommodations at the rapidly increasing numbers of hotels and commercial camps catering principally to fishermen—and, as it turned out, fisherwomen.

Fly fishing, rather than fishing with live bait or cast lures, was the fishing style of choice at Rangeley, and no one in the last decades of the 19th century devoted greater energy to the promotion of fly fishing, the Rangeley Lakes, and Maine in general as a sporting destination than Cornelia T. “Fly Rod” Crosby (1854–1946). Crosby’s accomplishments as a writer and personality were part of a larger effort conducted by a number of individuals, businesses, and state agencies to boost Maine’s economy through tourism at a time when the state’s agricultural strength was declining and its manufacturing industries were facing ever-increasing competition from southern New England mill towns.

In 1895, long before “Vacationland” appeared on Maine motor vehicle license plates (that happened in 1936), the Maine Sportsman’s Fish and Game Association claimed that hunting, fishing and related support services constituted the state’s most important source of income. The association lobbied for all businesses with an interest in tourism (including, significantly, the Maine Central Railroad), and heavily influenced commercial development in Maine as a tourist destination. The association also pressed for legislation establishing fish and game regulations, typically to benefit the out-of-state visitors, or “sports,” who came for the hunting and fishing.

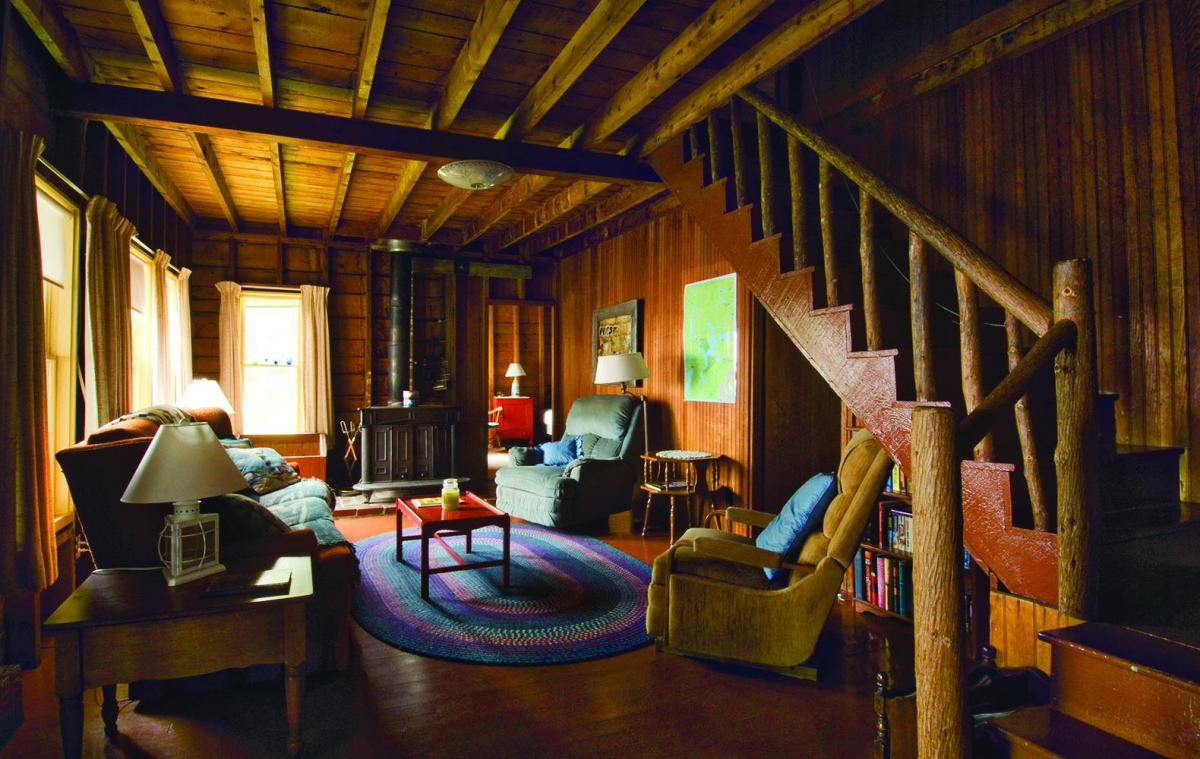

This photo shows the main room at the now-privately owned Belcher Camp in Rangeley as it looks today. The cottage once was part of the Mingo Springs Resort, which was started by a man named F.C. Belcher. Photo courtesy W. Tad Pfeffer

This photo shows the main room at the now-privately owned Belcher Camp in Rangeley as it looks today. The cottage once was part of the Mingo Springs Resort, which was started by a man named F.C. Belcher. Photo courtesy W. Tad Pfeffer

The fishing camps are Rangeley’s unique architectural contribution. Originating in the simplest concepts of shelter—roof and hearth—these camps became something more than rustic cabins by virtue of their shared use, either by paying clients or by members of a private club who shared in a camp’s use and ownership.

A circa 1873-78 view showing the dormitory in the main building of the Oquossoc Angling Association’s fishing camp. Photo courtesy W. Tad Pfeffer

The first private fishing club in the Rangeley region, the Oquossoc Angling Association, was founded in 1868 by George S. Page and several fellow fishing enthusiasts. Page and his colleagues bought a substantial parcel of land on Cupsuptic Lake, where they built their headquarters and base of operations. Camp Kennebago was designed for shared use by the association’s members, and consisted of a large dormitory and adjacent kitchen and dining area, all contained in a rectangular space some 100 feet long by 30 feet wide and open to the ridge of a single gable roof. The interior space was minimally divided—the single dormitory contained at least 13 beds—and was entirely unfinished. Privacy was neither expected nor desired. An adjacent building provided separate rooms for married couples, and eventually private cabins were added for members with families.

A circa 1873-78 view showing the dormitory in the main building of the Oquossoc Angling Association’s fishing camp. Photo courtesy W. Tad Pfeffer

The first private fishing club in the Rangeley region, the Oquossoc Angling Association, was founded in 1868 by George S. Page and several fellow fishing enthusiasts. Page and his colleagues bought a substantial parcel of land on Cupsuptic Lake, where they built their headquarters and base of operations. Camp Kennebago was designed for shared use by the association’s members, and consisted of a large dormitory and adjacent kitchen and dining area, all contained in a rectangular space some 100 feet long by 30 feet wide and open to the ridge of a single gable roof. The interior space was minimally divided—the single dormitory contained at least 13 beds—and was entirely unfinished. Privacy was neither expected nor desired. An adjacent building provided separate rooms for married couples, and eventually private cabins were added for members with families.

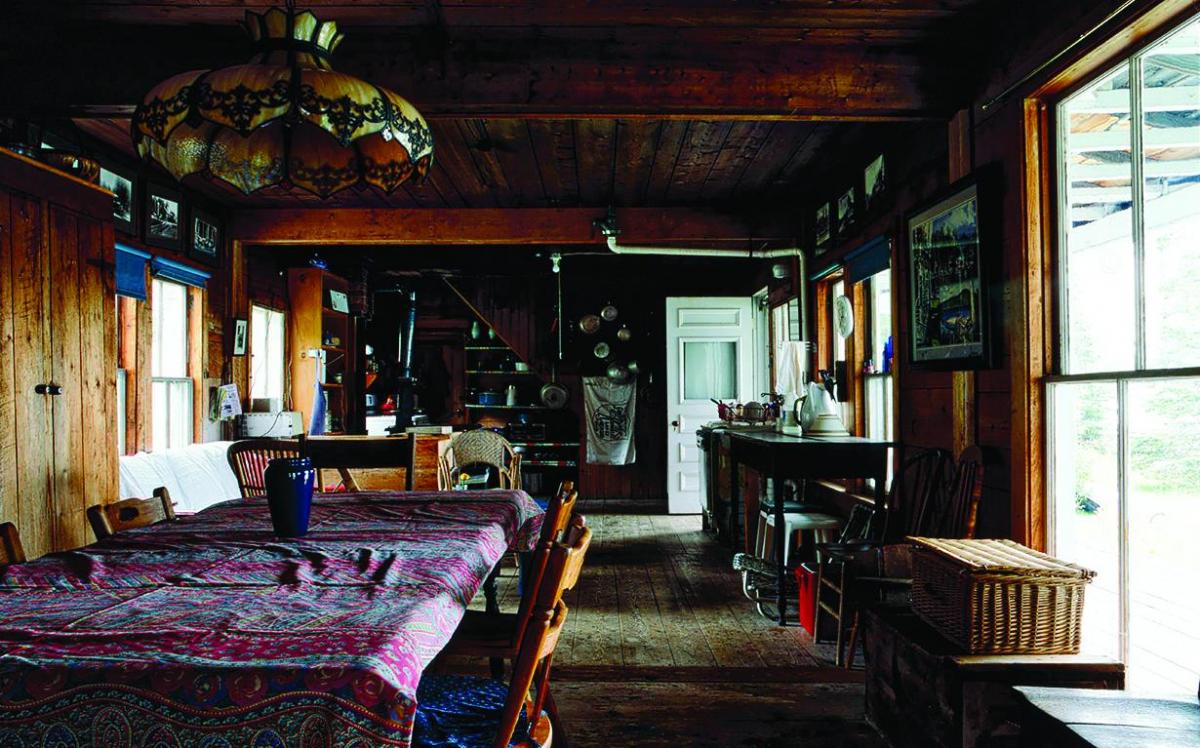

A contemporary view of the kitchen and dining room at Camp Kemankeag in Rangeley. The building was once part of a fishing club. Photo courtesy W. Tad Pfeffer

The need to provide services to clients efficiently required some compartmentalization of space by use, for example into service, kitchen, and dining areas, but these needs were met without completely isolating those spaces as they might be in a conventional hotel. Communal spaces shared by loosely connected acquaintances linked by a common interest in fishing created an atmosphere of informal collegiality and reinforced the rustic nature of their activity and setting. The services and accommodations were simple, comfortable without being indulgent. Buildings were deliberately functional, often built for use and occupancy by large numbers. Activities like dining, sleeping, and socializing would often have separate structures. The origins of this style of compound architecture are unknown but became common, particularly in lake settings, across northern New England.

A contemporary view of the kitchen and dining room at Camp Kemankeag in Rangeley. The building was once part of a fishing club. Photo courtesy W. Tad Pfeffer

The need to provide services to clients efficiently required some compartmentalization of space by use, for example into service, kitchen, and dining areas, but these needs were met without completely isolating those spaces as they might be in a conventional hotel. Communal spaces shared by loosely connected acquaintances linked by a common interest in fishing created an atmosphere of informal collegiality and reinforced the rustic nature of their activity and setting. The services and accommodations were simple, comfortable without being indulgent. Buildings were deliberately functional, often built for use and occupancy by large numbers. Activities like dining, sleeping, and socializing would often have separate structures. The origins of this style of compound architecture are unknown but became common, particularly in lake settings, across northern New England.

The Rangeley camps were distinguished from their contemporaneous Adirondack counterparts by their consistently utilitarian function. In the Adirondacks, the Adirondack Lodge style was quickly eclipsed by “Great Camps,” which took the basic functionality of the fishing camp and transformed it into a social and aesthetic display not unlike the “cottages” of Newport and Bar Harbor. By retaining their simple style and construction, the Rangeley camps continued to embody the most essential elements of shelter, physical and emotional communication with the environment, and communal experience of nature, ultimately becoming iconic representations of robust outdoor living. The style was adopted (first at Squam Lake in New Hampshire, in 1881) as the prototype for summer youth camp architecture.

Once part of the Mingo Springs Resort, this camp is now privately owned. An old view of the same camp shows a row of adjacent camp buildings connected by a boardwalk. Image courtesy W. Tad Pfeffer

Fishing wasn’t the only activity that made Rangeley such a popular destination in its boom years. The lakes also offered health resorts and vacation hotels oriented, unlike the camps, more toward leisure than sport. Between 1860 and World War II, more than 100 hotels, clubs, and commercial camps operated on the shores of the big lakes. The large establishments—hotels of 100 rooms and more—were beautiful buildings. But changes in the mobility of vacationers following World War II, combined with changing expectations of what summer resorts had to offer, led to the closure and eventual disappearance of the great resort hotels, not just at Rangeley, but across New England.

Once part of the Mingo Springs Resort, this camp is now privately owned. An old view of the same camp shows a row of adjacent camp buildings connected by a boardwalk. Image courtesy W. Tad Pfeffer

Fishing wasn’t the only activity that made Rangeley such a popular destination in its boom years. The lakes also offered health resorts and vacation hotels oriented, unlike the camps, more toward leisure than sport. Between 1860 and World War II, more than 100 hotels, clubs, and commercial camps operated on the shores of the big lakes. The large establishments—hotels of 100 rooms and more—were beautiful buildings. But changes in the mobility of vacationers following World War II, combined with changing expectations of what summer resorts had to offer, led to the closure and eventual disappearance of the great resort hotels, not just at Rangeley, but across New England.

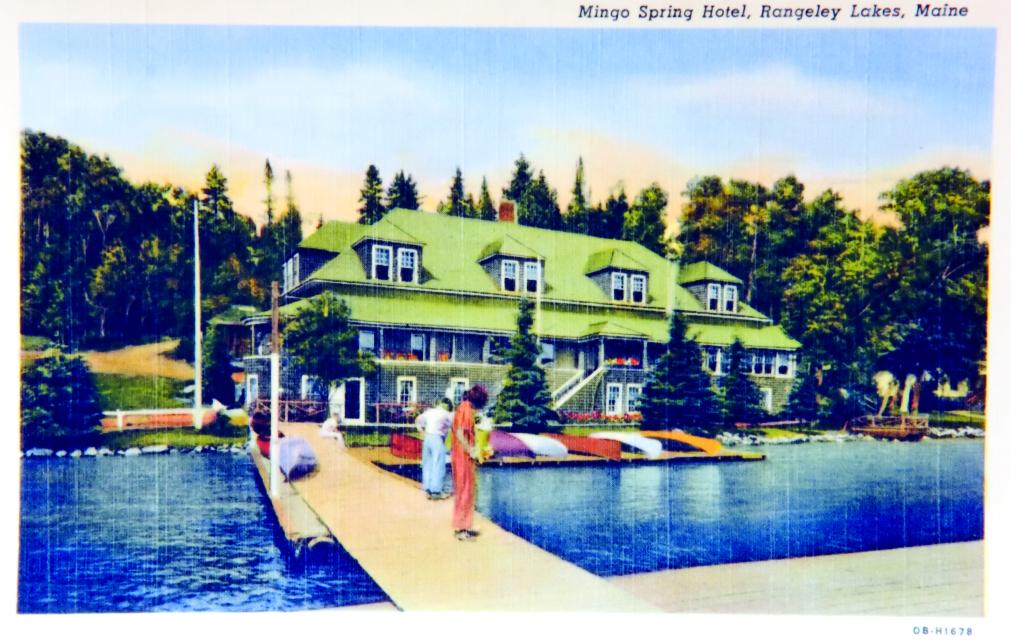

A vintage postcard of the Mingo Springs Resort, which closed in 1964 and was subdivided. Image courtesy W. Tad Pfeffer

Many of the individual cottages that surrounded the hotels, most built as annexes to the hotels themselves and integral to the hotel property, have survived and are now in private ownership. These surviving cottages share many of the qualities of summer houses on the Maine coast; the fishing camps less so. The camps are the product of a building up of primitive units of shelter and hearth, possibly through an intermediate tent phase, to create a domestic dwelling for simplified or occasional use, while the cottages are a scaling down of traditional or “conventional” domestic architecture for essentially the same purpose. Ultimately, though, the differences vanish and the distinction becomes academic.

A vintage postcard of the Mingo Springs Resort, which closed in 1964 and was subdivided. Image courtesy W. Tad Pfeffer

Many of the individual cottages that surrounded the hotels, most built as annexes to the hotels themselves and integral to the hotel property, have survived and are now in private ownership. These surviving cottages share many of the qualities of summer houses on the Maine coast; the fishing camps less so. The camps are the product of a building up of primitive units of shelter and hearth, possibly through an intermediate tent phase, to create a domestic dwelling for simplified or occasional use, while the cottages are a scaling down of traditional or “conventional” domestic architecture for essentially the same purpose. Ultimately, though, the differences vanish and the distinction becomes academic.

As Rangeley’s status as a commercial resort destination declined during and following World War II, its camps and cottages started to pass into private hands. The clustered, multiple-structure style of the fishing camps lent itself well to occupancy by extended families and multiple generations. Here, as in so many summer communities, the camp or cottage often became the annual meeting place for extended families scattered geographically and across generations. Frequently the family camp became the true “home,” the one fixed and unvarying place where grandparents, children, and grandchildren shared not only a common experience, but to a large degree a common identity as each passed through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood in a place far less variable and evolving than what was experienced in the “real” world of careers and modern life.

This article was adapted from The Hand of the Small-Town Builder: Summer Houses in Northern New England, 1876-1930 by W. Tad Pfeffer (David R. Godine, 2014, 200 pages, hardcover).

This article was adapted from The Hand of the Small-Town Builder: Summer Houses in Northern New England, 1876-1930 by W. Tad Pfeffer (David R. Godine, 2014, 200 pages, hardcover).

W. Tad Pfeffer is a geophysicist, teacher, and photographer at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He is a Fellow of the university’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research and Professor in the Department of Civil, Environmental, and Architectural Engineering.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.