Rebirth for a historic mill

Year-long restoration breathes new life into the community

By Polly Saltonstall

The newly restored building perches next to a dam where owners plan to install water-powered electric turbines in 2014. Photograph courtesy Tony Grassi

By Polly Saltonstall

Sometimes it takes a building to build a community. Or maybe it’s the building process that builds community.

Whichever, the visionary year-long restoration of an old water-powered mill in Freedom, Maine, brought together engineers, woodworkers, stone masons, and other craftsmen sharing talents. The finished structure now anchors a growing network of children, farmers, and food lovers on a site that had been vacant and decaying for more than 40 years.

The newly restored building perches next to a dam where owners plan to install water-powered electric turbines in 2014. Photograph courtesy Tony Grassi

By Polly Saltonstall

Sometimes it takes a building to build a community. Or maybe it’s the building process that builds community.

Whichever, the visionary year-long restoration of an old water-powered mill in Freedom, Maine, brought together engineers, woodworkers, stone masons, and other craftsmen sharing talents. The finished structure now anchors a growing network of children, farmers, and food lovers on a site that had been vacant and decaying for more than 40 years.

The sagging old building

had been abandoned for 46 years.

Photo by Lynn Karlin

“I hope people in communities around here will see old buildings in a new light and be inspired,” he said.

Built in 1834 when local mills anchored small farming communities across Maine, the Freedom Mill ground grain between huge granite stones (a pair found during the renovation is now displayed outside) until 1894 when it was converted to a turning mill, producing such wooden products as dowels, tool handles, clothes pins, and even toothpicks. Eventually the arrival of plastic products and a decline in hardwood put the mill and many others like it out of business and the building was abandoned in 1967.

These transitions mirror shifts in Maine from an agrarian economy in the 1800s, to an era driven by demand for wood products in the early 1900s, to the present day, when a new generation of young people, such as Prentice Grassi and his sister Laurie Grassi-Redmond, who runs the new Mill School, are rediscovering farming and the appeal of rural communities.

Grassi-Redmond, who has a Master’s degree in education, had taught at the Belgrade Lakes School and in California before starting the Mill School. Both she and her husband, Chris Redmond, who is from Maine, liked the idea of moving back.

“The family had been thinking what is the highest and best use for the mill,” said Grassi-Redmond. “My sister-in-law [Shyka] said that next to feeding people the most important thing is teaching children. She asked, ‘would you consider starting a school here?’”

Grassi-Redmond worried at first whether enough children would enroll in the new school, which offers three-day-a-week, place-based learning for homeschooled children ages 5-11. By opening day, however, all 20 slots had been filled and there was a waiting list.

The sagging old building

had been abandoned for 46 years.

Photo by Lynn Karlin

“I hope people in communities around here will see old buildings in a new light and be inspired,” he said.

Built in 1834 when local mills anchored small farming communities across Maine, the Freedom Mill ground grain between huge granite stones (a pair found during the renovation is now displayed outside) until 1894 when it was converted to a turning mill, producing such wooden products as dowels, tool handles, clothes pins, and even toothpicks. Eventually the arrival of plastic products and a decline in hardwood put the mill and many others like it out of business and the building was abandoned in 1967.

These transitions mirror shifts in Maine from an agrarian economy in the 1800s, to an era driven by demand for wood products in the early 1900s, to the present day, when a new generation of young people, such as Prentice Grassi and his sister Laurie Grassi-Redmond, who runs the new Mill School, are rediscovering farming and the appeal of rural communities.

Grassi-Redmond, who has a Master’s degree in education, had taught at the Belgrade Lakes School and in California before starting the Mill School. Both she and her husband, Chris Redmond, who is from Maine, liked the idea of moving back.

“The family had been thinking what is the highest and best use for the mill,” said Grassi-Redmond. “My sister-in-law [Shyka] said that next to feeding people the most important thing is teaching children. She asked, ‘would you consider starting a school here?’”

Grassi-Redmond worried at first whether enough children would enroll in the new school, which offers three-day-a-week, place-based learning for homeschooled children ages 5-11. By opening day, however, all 20 slots had been filled and there was a waiting list.

Laurie Grassi-Redmond says the

new alternative school already

has a waiting list of prospective

students.

Photo by Tony Grassi

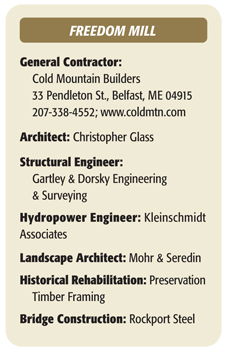

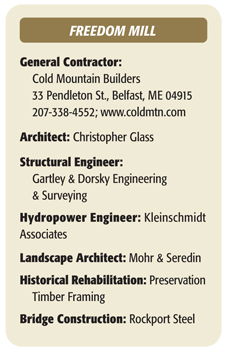

The restoration, coordinated by Cold Mountain Builders of Belfast, involved a team skilled in preservation and old construction techniques, including architect Christopher Glass of Camden, Arron Sturgis of Preservation Timber Framing in Berwick, stone mason Rod Bishop, and landscape architect Stephen Mohr.

A section of the building that had been added in later years was removed and replaced with an identical annex on the same footprint. Other changes were made to bring the structure up to code. The nearby dam and the mill’s granite underpinnings, including the waterway underneath, were rebuilt and massive new timbers installed in places where the old ones had rotted. This was an intricate job. The original timber framing, put together in such a way as to allow the building to withstand intense vibrations from gears and water, had held up remarkably well, said Jay Fischer of Cold Mountain Builders. Still, since Grassi was able to get the building listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the renovations had to be done to exact standards.

Laurie Grassi-Redmond says the

new alternative school already

has a waiting list of prospective

students.

Photo by Tony Grassi

The restoration, coordinated by Cold Mountain Builders of Belfast, involved a team skilled in preservation and old construction techniques, including architect Christopher Glass of Camden, Arron Sturgis of Preservation Timber Framing in Berwick, stone mason Rod Bishop, and landscape architect Stephen Mohr.

A section of the building that had been added in later years was removed and replaced with an identical annex on the same footprint. Other changes were made to bring the structure up to code. The nearby dam and the mill’s granite underpinnings, including the waterway underneath, were rebuilt and massive new timbers installed in places where the old ones had rotted. This was an intricate job. The original timber framing, put together in such a way as to allow the building to withstand intense vibrations from gears and water, had held up remarkably well, said Jay Fischer of Cold Mountain Builders. Still, since Grassi was able to get the building listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the renovations had to be done to exact standards.

Parts of the old building, including the original doors, many of the timbers and some siding as well as some bits of machinery, were strategically left in place. Old turbines and other equipment have been installed in a museum downstairs that tells the story of the mill, its original builders, and the recent restoration. Plans are under way to install new water-powered electric turbines in 2014, which will generate enough power to run 10 homes. Already installed is a heating and cooling system that uses water from the millpond.

The process was long and took some unexpected turns. Still, Tony Grassi could not be more pleased with the results.

“It was a labor of love and time, and a legacy that Sally and I can leave to the state,” he said.

MBH&H Editor in Chief Polly Saltonstall lived at one point on the site of an old lumber mill in Jefferson, Maine.

For More Information:

The Grassi family kept a detailed blog during the construction process. It can be found at http://www.millatfreedomfalls.com. Also, Compass Light Productions filmed a feature-length documentary on the project.

The 29-minute documentary "Reviving the Freedom Mill" tells the tale of an ambitious renovation project in rural Maine.

Video courtesy of Compass Light Productions.

Parts of the old building, including the original doors, many of the timbers and some siding as well as some bits of machinery, were strategically left in place. Old turbines and other equipment have been installed in a museum downstairs that tells the story of the mill, its original builders, and the recent restoration. Plans are under way to install new water-powered electric turbines in 2014, which will generate enough power to run 10 homes. Already installed is a heating and cooling system that uses water from the millpond.

The process was long and took some unexpected turns. Still, Tony Grassi could not be more pleased with the results.

“It was a labor of love and time, and a legacy that Sally and I can leave to the state,” he said.

MBH&H Editor in Chief Polly Saltonstall lived at one point on the site of an old lumber mill in Jefferson, Maine.

For More Information:

The Grassi family kept a detailed blog during the construction process. It can be found at http://www.millatfreedomfalls.com. Also, Compass Light Productions filmed a feature-length documentary on the project.

The 29-minute documentary "Reviving the Freedom Mill" tells the tale of an ambitious renovation project in rural Maine.

Video courtesy of Compass Light Productions.

The newly restored building perches next to a dam where owners plan to install water-powered electric turbines in 2014. Photograph courtesy Tony Grassi

The newly restored building perches next to a dam where owners plan to install water-powered electric turbines in 2014. Photograph courtesy Tony Grassi

“I hope people in communities around here will see old buildings in a new light and be inspired.”

An alternative school opened in the newly restored building last fall, along with the office of the Maine Federation of Farmers’ Markets. Work was under way at press time on a home in the mill for the Lost Kitchen, the acclaimed locavore restaurant formerly in Belfast. Instead of workers bent over machines, young children now roam the wood-paneled hallways. Diners soon will be eating in an airy room under huge gears and straps that once turned lathes.

When Camden residents Tony and Sally Grassi first saw the old mill, perched on the banks of gushing Sandy Stream, the structure was close to collapse. They visited it with their son, Prentice Grassi, who with his wife Polly Shyka had been raising vegetables and animals on Village Farm next door for almost 10 years. A former investment banker turned conservationist, Tony Grassi was intrigued with the idea of restoring the mill and using the water that once powered machines to generate electricity instead.

More importantly he wanted to fill the building with tenants who would make it as lively and integral to the community as it had been back in its days as a working mill. He also wanted to show that saving historic buildings sometimes makes more sense than building new ones.

The sagging old building

had been abandoned for 46 years.

Photo by Lynn Karlin

The sagging old building

had been abandoned for 46 years.

Photo by Lynn Karlin

Laurie Grassi-Redmond says the

new alternative school already

has a waiting list of prospective

students.

Photo by Tony Grassi

Laurie Grassi-Redmond says the

new alternative school already

has a waiting list of prospective

students.

Photo by Tony Grassi

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.