Water Ways: What’s On the Menu?

We love to eat lobsters, but what do lobsters love to eat?

By Melissa Waterman

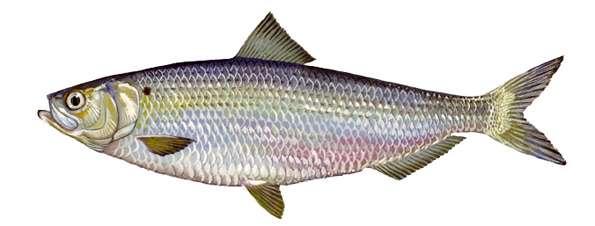

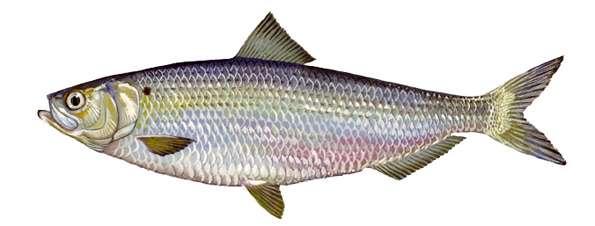

A victim of over fishing, the herring (a blueback pictured here), was plentiful and a preferred lobster bait.

A victim of over fishing, the herring (a blueback pictured here), was plentiful and a preferred lobster bait.

Courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.What a life Homarus americanus leads! People vie to write about him, scientists study his every movement, dozens of businesses and individuals base their entire livelihood on him, and each day hundreds upon hundreds of lobstermen entice him into their traps with delectable morsels of bait that only a lobster could love. Then they haul him to the surface, measure him, and—if he fails to measure up—toss him back into the ocean to dine some more. Not too bad for a belligerent crustacean.

It’s the lobstermen who have the difficult side of this relationship. They constantly must provide the right bait to lure the lobsters into their traps. That bait must have four basic qualities: it must be oily, it must be stinky, it must be relatively cheap, and it must last for a decent amount of time while submerged in the ocean.

The modern lobster trap serves as a fine dining establishment

The modern lobster trap serves as a fine dining establishment

for Homarus americanus. Photo by Melissa WatermanLobsters are led by their noses, so to speak. The creature has a remarkable olfactory system; if the bait is oily and smelly, it’s haute cuisine to a lobster. If it’s not, they will just walk on by.

Back in the 1800s, when Portland lobstermen were hauling in huge four- to six-pound lobsters every day of their four-month season, cod and haddock heads were the preferred bait. They met two of the criteria: they were rank and they were cheap. Unfortunately, such bait did not last long in the traps. Lobstermen also used fresh flounder and other bottom fish for bait, at least, they did when such fish were easily caught in coastal waters. Still, the fresh fish just didn’t last long under water.

During the 1900s, lobstermen in Maine turned to herring as their preferred lobster bait. In the old days herring were caught in weirs along the coast or by “torching” at night. “Torching” meant that a boat was lit up like a Christmas tree to attract schools of herring to the vessel and its nets. Herring also were caught in circular weirs made of wood and net as they moved up the coast; the fish entered the weir and then found themselves trapped within its core, unable to retreat.

Humans as well as lobsters liked to eat the oily little fish. Processing herring for sardines was one of Maine’s great industries at the turn of the century. Yet within the last 50 years, sardines have fallen out of favor with the American palate to the point where and Maine’s last commercial sardine cannery will probably be closed for good before too long. Nearly all the herring now harvested in Maine is used for lobster bait.

Though they once moved in vast schools of hundreds of thousands, herring, too, came upon hard times in the 1960s and 1970s. They were overfished in the Gulf of Maine by foreign fishing vessels, then, after institution of the Magnuson Fisheries Conservation and Management Act in 1977, they were overfished by American and Canadian vessels. Lobstermen found it hard to get herring at a price they could afford.

(As a digression, and because I like odd words, landed herring are still measured in hogsheads. A hogshead, from the Middle English hoggeshed, is equivalent to 1,150 pounds. Now you know.)

As a substitute for herring, lobstermen began using redfish and menhaden as bait. Brevoortia tyrannus, also known as pogys, occur off the mid-Atlantic states in huge schools of many tons. During the summer sub-units of the larger schools may migrate up the coast of Maine into small coves. Recreational fishermen know that when the pogys arrive, the ever-hungry bluefish won’t be far behind. While they are edible to humans, pogys have long been harvested commercially for their oil, which is used as an industrial lubricant. As lobster bait, pogys meet three of the criteria: they are oily and stinky and relatively durable underwater, but they are more expensive than herring.

It takes about seven years of being regularly fed before a lobster

It takes about seven years of being regularly fed before a lobster

reaches a harvestable size. Photo by Melissa WatermanThe demand for bait has increased in recent years, as lobstering has become Maine’s number-one fishery. Federal regulation and the vagaries of nature cause the supply of herring and pogeys to vary month to month and year to year. To keep /em>Homarus americanus happy, lobstermen have turned to truly unusual items as bait of late, including treated cowhide (which is certainly durable).

Scientists and lobstermen are still debating the safety of using truly artificial lobster bait in traps. Meanwhile, at the University of Maine in Orono, the Lobster Institute has come up with a soy-based lobster bait that it thinks actually surpasses herring. The soybean meal product is treated to emulate the smell of those things that lobsters like. According to a study by the institute, their soybean meal bait outperformed even the much-lauded herring. Further improvements to this miracle bait are under way.

It takes approximately seven years for a lobster to reach harvestable size. Imagine, if you will, the many years of delectable dining that have been enjoyed by the seven (or more)-year-old lobster: breakfasts of rancid herring, luncheons of dissolved redfish, leisurely dinners of oily pogys, all consumed in the company of its undersized companion lobsters. One could look at the great squadrons of eager lobstermen as the very finest of waiters—hovering attentively above, and tending to the crustacean’s every culinary demand.

A victim of over fishing, the herring (a blueback pictured here), was plentiful and a preferred lobster bait.

A victim of over fishing, the herring (a blueback pictured here), was plentiful and a preferred lobster bait.Courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The modern lobster trap serves as a fine dining establishment

The modern lobster trap serves as a fine dining establishment for Homarus americanus. Photo by Melissa Waterman

It takes about seven years of being regularly fed before a lobster

It takes about seven years of being regularly fed before a lobster reaches a harvestable size. Photo by Melissa Waterman

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.