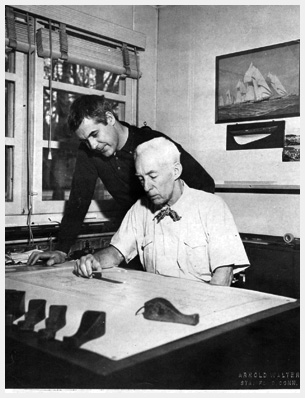

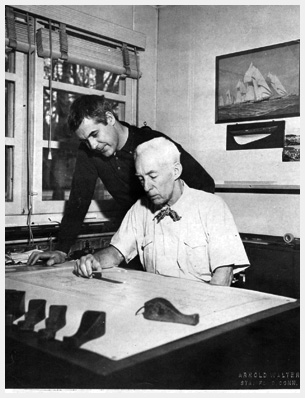

William Atkin at the drawing board with his son looking on.

Photo courtesy the Atkin family.

We continue our series of short biographical sketches, remembering those who influenced how we respond to boats, ships, and the sea.

William Atkin

"Billy" to all who knew him.

“If there is anything more interesting to watch than the construction of a small boat I should like to hear about it,” William Atkin (1882-1962) wrote in

Of Yachts and Men, his homage to the boats he designed and built, and the people he came to know during a long, happy career. “And if the boat happens by some good fortune to be a child of your brain or a child of your affluence, well then the charm of building is twofold.”

“Enthusiastic” should have been William Atkin’s middle name. Brimming with infectious enthusiasm, he encouraged untold thousands of youngsters and adults during the decades of the middle third of the twentieth century to build boats, sail boats, enjoy boats—big, small, or anything in between. He did this by designing and writing about them in the boating magazines of the day—

Motor Boating,

The Rudder,

Motor Boat,

Pacific Motor Boat,

Yachting, and his own, short-lived magazine,

Fore an’ Aft—and in several books, many of which remained in print for years. (During several years he designed a boat each month for

Motor Boating and described how to build it.) While today he is best known for his small-craft designs, during his heyday his fame was centered on heavy-displacement double-ended cruising boats.

Atkin wrote about designs, not production models; how to do things for yourself, not how to have others do them for you; how to make things from scratch, not to buy ready-made items off the shelf. A boatbuilder in his own right, and an avid sailor, he understood the interests of his readers.

He was of an earlier, happier time when boats weren’t seen as consumer products, or boatbuilding as an industry, or boat design as a tedious exercise in getting more berths and more power into less space, or boat selling as another way to create demand for equity loans and insurance policies.

To gain an appreciation of William Atkin’s spirit, read the first five chapters of

Of Yachts and Men. To gain an understanding of the source of his eclectic interests, read all of

The First Book of Boats and its sequel,

The Second Book of Boats.

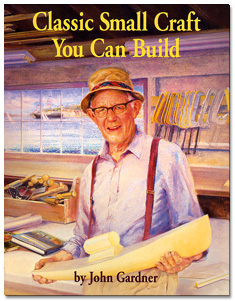

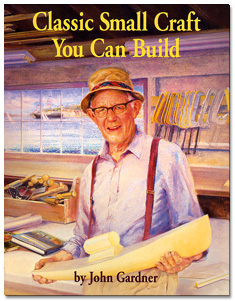

Gardner in the Mystic Seaport boatshop he founded.

In the years of America’s greatest prosperity, beginning in the 1960s, when boats for even the common man were getting bigger, more elaborate, and more expensive, John Gardner, a man of the intellect as well as of the hand, preached the gospel of small craft. “Building and using a small wooden boat,” he wrote, “helps wonderfully to reestablish and strengthen connections with the natural world that so many of us have lost or are in increasing danger of losing. Wind and water have not changed, and the age-old workings and needs of the human body and psyche remain the same and cry for expression and fulfillment in a cold world of artificial abstractions and flickering images.”

Born in Calais, Maine, John Gardner (1905-1995) was a boatbuilder of the old school, having learned under the tutelage of several of the best craftsmen of the time. As a young man he studied to be a teacher at the Maine Normal School; later, he earned a master’s degree in education at Columbia University. During the 1930s he worked as a labor organizer for the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

Gardner’s full-time boatbuilding career began when he took charge of a summer-camp boatshop in the Belgrade Lakes, Maine. He then went on to become a leading hand at several of the best Massachusetts yacht yards, including Grave’s in Marblehead and Dion’s in Salem. Fascinated by traditional small craft, he began to collect information about the evolution of small-craft design and construction, and to publish articles about the subject in the

Maine Coast Fisherman and its successor, the

National Fisherman, becoming the latter’s technical editor.

Gardner wrote about boats and boatbuilding of the past, with an emphasis on adapting them to the present. In 1969 he became the associate curator of small craft at the Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut, where he set up and ran a pioneering boatbuilding program to teach amateurs the skills of the past and helped establish an annual small-craft gathering that brought enthusiasts from far and wide. His books include

Building Classic Small Craft,

Wooden Boats to Build and Use,

More Building Classic Small Craft, and

The Dory Book.

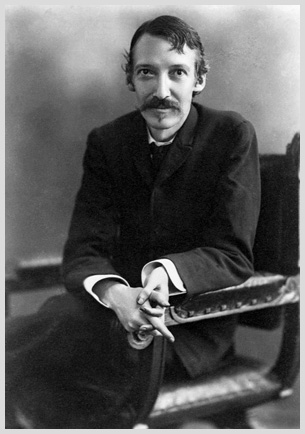

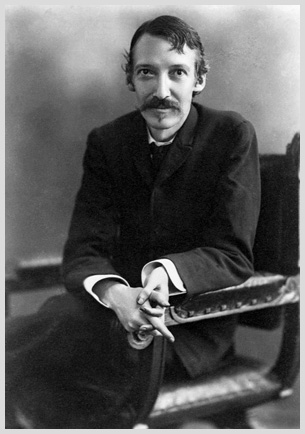

Author, traveler, adventurer, and the inspiration behind

many youngsters’ dreams. Photo ©Bettman/CORBIS

Jim Hawkins, Billy Bones, Long John Silver, Blind Pew, the

Hispaniola—who can forget these names from

Treasure Island, considered by many to be the greatest pirate yarn ever written? Who hasn’t read, or at least heard of,

Kidnapped,

The Master of Ballantrae,

A Child’s Garden of Verses, or

In the South Seas? All of these and more are from the pen of Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894), who published more in his short career than most writers did in twice the time and who caused countless youngsters to dream of a life of adventure, especially on the sea. A master of the romantic tale, he knew how to spin a yarn and didn’t need “special effects” to juice it up.

Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. As a young man attending Edinburgh University, he was notable for his bohemian style of life and for his interest in the art of writing, even though his stated course of study was engineering. (His original intention had been to follow in the footsteps of his father, Thomas Stevenson, Britain’s most accomplished lighthouse engineer.) Changing course, he studied law, receiving his degree in 1875. Yet from that point on, Stevenson considered himself a writer and supported himself at that trade.

Stevenson was an ardent traveler, and among his first and later works of note were books about his experiences, including

An Inland Voyage, about a double-paddle canoe trip on the rivers and canals of France, and

Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes. His first critically acclaimed work of fiction,

Treasure Island, was published in 1883. He lived variously in Scotland, the United States, Switzerland, France, and, after a long cruise by yacht through the South Seas, Samoa.

Here are a few words about the Zen of paddling, from Stevenson’s

An Inland Voyage:

“Something inside my mind,” he wrote, “a part of my brain, a province of my proper being, had thrown off allegiance and set up for itself, or perhaps for the somebody else who did the paddling. I had dwindled into quite a little thing in a corner of myself. I was isolated in my own skull. Thoughts presented themselves unbidden; they were not my thoughts, they were plainly some one else’s; and I considered them like a part of the landscape. I take it, in short, that I was about as near Nirvana as would be convenient in practical life; and, if this be so, I make the Buddhists my sincere compliments; ’tis an agreeable state, not very consistent with mental brilliancy, not exactly profitable in a money point of view, but very calm, golden, and incurious, and one that sets a man superior to alarms. It may be best figured by supposing yourself to get dead drunk, and yet keep sober to enjoy it.”

Peter H. Spectre is the editor of this magazine. He is himself a small-boat enthusiast and story-teller.

William Atkin at the drawing board with his son looking on.

William Atkin at the drawing board with his son looking on.  Gardner in the Mystic Seaport boatshop he founded.

Gardner in the Mystic Seaport boatshop he founded. Author, traveler, adventurer, and the inspiration behind

Author, traveler, adventurer, and the inspiration behind