Influenced by Nature

Early Maine sailing vacations inspired a land conservation movement

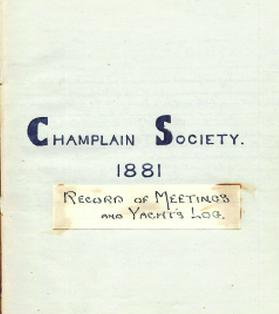

Members of the Champlain Society posed for a photo in 1881 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, before setting off for their second summer in Maine. Founded by Charles Eliot, the society was a group of Harvard College undergraduates interested in documenting the natural history of Mt. Desert Island. Their work helped inspire land conservation efforts on the island and beyond. Photograph courtesy Mount Desert Island Historical Society

Members of the Champlain Society posed for a photo in 1881 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, before setting off for their second summer in Maine. Founded by Charles Eliot, the society was a group of Harvard College undergraduates interested in documenting the natural history of Mt. Desert Island. Their work helped inspire land conservation efforts on the island and beyond. Photograph courtesy Mount Desert Island Historical Society

In May 1871, Charles William Eliot had been president of Harvard University barely two years, and a widower just as long. He needed a break, for himself and his two young sons, a “thorough vacation” in the open air, as he wrote to a friend.

He found means in the Jessie, a 33-foot sloop, and began planning a sailing and camping trip to Maine, “down Mount Desert way.” Described as “a very pretty boat and tolerably fast,” the Jessie and crew made a few warm-up excursions around Boston Harbor and raced with the Dorchester Yacht Club before leaving for Maine in July. Captained by Eliot (with assistance from a hired sailor) and crewed by his brother-in-law, Charles Eliot Guild, nephew Robert Wheaton Guild, and Arthur C. Kelley of Neponset, the boat was jammed full of camping gear, leaving little room for the passengers in the four berths.

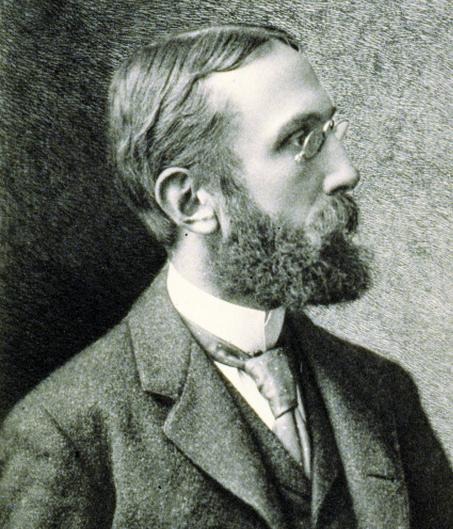

They reached Portland in a day, then sailed on to anchorages in Herring Gut and the Deer Isle Thorofare. As they made Bass Harbor Light on the third day out, the fog cleared away. They passed Long Ledge and Great Cranberry Island and sailed into Southwest Harbor. Charles Eliot in 1897 at age 33. From Charles Eliot Landscape Architect, by Charles William Eliot

Charles Eliot in 1897 at age 33. From Charles Eliot Landscape Architect, by Charles William Eliot

This cruise and summer of camping, the first of many, helped instill in Eliot, and especially his son Charles, a sense of place that would have a lasting impact on the Mt. Desert region and beyond. The younger Charles Eliot, who became a landscape architect and partner in the firm of Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., would go on to lead the first natural history surveys of Mt. Desert Island in the 1880s. Later, when he helped found The Trustees of Reservations in Massachusetts in 1891, he created the land trust model that would be used to protect Mt. Desert Island’s diverse landscapes, and other places around the world. Sailing and camping on Frenchman Bay was a formative experience that changed the Eliots’ lives. Their conservation leadership made it possible for millions of people to enjoy the same experience today.

At the time, the concept of cruising the coast for pleasure was just beginning to take off. Robert Carter, Washington correspondent for the New York Tribune, had published a serialized account of his cruise on the chartered sloop Helen to Mt. Desert in 1858 (the newspaper articles were published in book form as the classic A Summer Cruise on the Coast of New England). An 1867 New York Times article noted the visit of the newly formed Boston Yacht Club to Southwest Harbor. But in contrast to the Eliots, most visitors to Mt. Desert arrived via some combination of train, steamship, and carriage, and boarded with local residents or stayed in hotels.

Charles Eliot and fellow members of The Champlain Society sailed his father’s yacht Sunshine on the first of what became many annual expeditions to Mt. Desert Island. The Eliot family had spent summers in the region since Charles was young and he wanted to share the experience with his classmates. This photo of the yacht was taken July 20, 1881 by Marshall P. Slade, a member of the group. Photographs courtesy Mount Desert Island Historical Society (2)

Charles Eliot and fellow members of The Champlain Society sailed his father’s yacht Sunshine on the first of what became many annual expeditions to Mt. Desert Island. The Eliot family had spent summers in the region since Charles was young and he wanted to share the experience with his classmates. This photo of the yacht was taken July 20, 1881 by Marshall P. Slade, a member of the group. Photographs courtesy Mount Desert Island Historical Society (2)

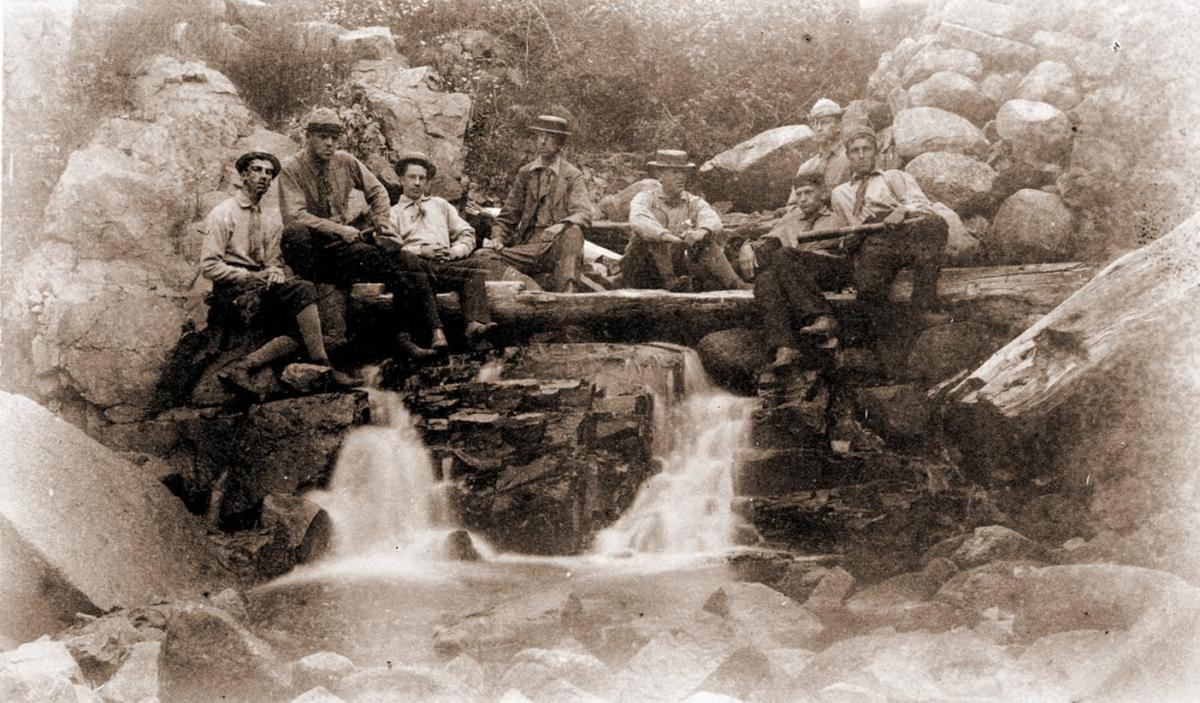

Members of the Champlain Society in 1881 at Hadlock Brook, near their Northeast Harbor base camp.

Members of the Champlain Society in 1881 at Hadlock Brook, near their Northeast Harbor base camp.

The log of the 1871 cruise and subsequent ones, preserved by the Mt. Desert Island Historical Society, describe what sailing was like in those early years. Travel was still fairly rustic, and that was the idea. Sailing was a natural extension of a desire to get out of the crowded city, and was faster and more calming than a bumpy carriage ride, crowded train, or steamship. These “were people who loved the outdoors enough to actually get out in it,” wrote one scholar.

The day after arriving in Southwest Harbor, the Jessie continued east around the island, passing seven Eastern Yacht Club yachts off Schooner Head on their way to Ironbound Island. The Eastern and Dorchester Yacht Clubs both formed in 1870; this was likely the first summer excursion of the inaugural Eastern Yacht Club fleet.

Eliot steered the Jessie north along the Gouldsboro peninsula, past Jordan and Stave islands to Calf Island and its outlying Thrumcap and Little Calf. There he edged the boat onto a curved, narrow beach. After getting permission from the owners, the Eliots established a camp, which they called “Camp Sunshine,” on Calf Island. They slept on hay mattresses with rubber pillows in walled canvas tents. There was also a large dining-room tent and a kitchen tent and a flagpole to salute passing boats.

Most of the small island had been cleared of trees but a few spruce and pine still lined the shores. The family that owned the island had abandoned its farm there a few years earlier, although a son still cut hay in the fields, and a few oxen grazed where the Eliots established their summer home. Five miles west, the dark blue of the Porcupine Islands separated the blue of the bay from the highest hills of Mount Desert. The sea breeze blew across the island, shimmering the green meadow grass and keeping mosquitoes away.

Eliot and his crew were soon joined by his boys, Charles, 11, and Sam, 8, and their attending nursemaid; the elder Eliot’s sister Frances, and her husband, the Rev. Henry Wilder Foote (minister at King’s Chapel in Boston); and their daughter, Mary.

The family spent the summer tasting the salt of coastal life, picnicking, chasing butterflies, and combing woods and wrack lines for treasures. According to Charles William Eliot’s biographer Henry James, a sense of novelty and excitement was part of the fun. “Once away on these holidays, Harvard and his ordinary cares seemed to drop out of Eliot’s mind. The sea, the wind, the day and its small adventures, the procuring of supplies, the sailing of the boat absorbed him completely.”

Back in Cambridge that fall, Eliot knew he would return to Calf Island. He made plans to sell the Jessie and started looking for a vessel better suited to extended cruising.

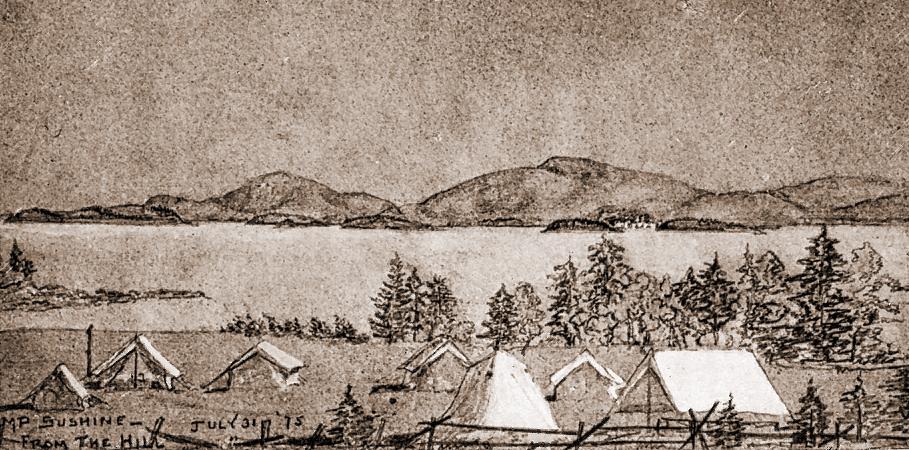

During the Eliot family’s first cruise to Mt. Desert Island, they set up camp on Calf Island in Frenchman Bay opposite Bar Harbor. Charles Eliot drew this sketch of the camp, later printed in a Pulitzer-prize winning biography of his father, Charles William Eliot, by Henry James (nephew to the well-known novelist). From Charles W. Eliot by Henry James

During the Eliot family’s first cruise to Mt. Desert Island, they set up camp on Calf Island in Frenchman Bay opposite Bar Harbor. Charles Eliot drew this sketch of the camp, later printed in a Pulitzer-prize winning biography of his father, Charles William Eliot, by Henry James (nephew to the well-known novelist). From Charles W. Eliot by Henry James

Built by Albertson Brothers of Philadelphia, the new sloop, Sunshine, was 43½ feet long, had a cabin tall enough to accommodate Eliot standing up, and room enough for four adults and two children. James called it “one of the first American yachts designed specifically for cruising along the New England coast.”

The Eliots returned to Calf Island in 1872 and every subsequent summer through 1878, with the exception of 1873 when they went to Cape Cod. With the Coast Survey’s Atlantic Coast Pilot as a guide, and the historic voyages of Samuel de Champlain as inspiration, the family came to know the harbors, shoals, islands, and beaches of the Maine coast.

In the spring of 1880, the elder Eliot announced that he and his second wife, Grace, would be traveling in Europe for the summer. He offered the yacht and camping gear to Charles and Sam, then students at Harvard College, who jumped at the chance to sail downeast and camp on Mt. Desert Island. The younger Charles invited friends and classmates to be part of an expedition, in which each member would “do some work in some branch of natural history or science.” They named their club the Champlain Society.

Charles Eliot sailed Sunshine from Boston to Mt. Desert with the help of Orrin Donnell, a young man from Sullivan who was hired as boatman. They established “Camp Pemetic” on the eastern shore of Somes Sound near the outlet of Hadlock Brook. Sunshine was moored close by.

Champlain Society members chose which “specialty” or department they would contribute to: collecting flowers for the botanical department, dredging for marine invertebrates, shooting birds for the ornithology department, recording the weather from their meteorological station, or surveying geology. They fished for food and for science. They often walked to and from camp, and used boats (“the little boat,” “the white boat,” “the black boat,” the dory Fair Play) rented from local residents. Sunshine enabled them to roam farther and expand their collections.

Every few days they sailed Sunshine to Southwest Harbor for mail, provisions, and to pick up or drop off members and visitors at the steamship landing. Somesville was another regular port of call. They took longer sails around the island, to the Cranberry Isles, to Greenings and Suttons islands, “bumming tours” to socialize in Bar Harbor, and to explore Frenchman Bay and beyond. Entries from the yacht’s log describe their daily activities.

In 1882 the Champlain Society moved its camp to Asticou, at the head of Northeast Harbor, so that the members could eat at the Savage family’s inn instead of hiring a cook—Camp Asticou was also closer to the Eliots’ new summerhouse. The Champlain Society borrowed Savage’s sailboats, the Eddie, Vyvyan, and another “very stiff boat” which they named Junco, “after the wife of that noble chieftain Asticou who has kindly allowed us to give his name to our camp.” Donnell was not hired as boatman, so members of the party “were doomed to do all their own work,” according to a log entry.  This majestic view of Sutton and the Cranberry Islands was taken from the top of Penobscot Mountain in Acadia National Park. Charles Eliot and his father helped start the conservation movement that led to the park’s creation. Photograph by Linda Lunt

This majestic view of Sutton and the Cranberry Islands was taken from the top of Penobscot Mountain in Acadia National Park. Charles Eliot and his father helped start the conservation movement that led to the park’s creation. Photograph by Linda Lunt

As early as 1881, the Champlain Society began to express concern for the island’s future, and to initiate plans for its protection as publicly accessible land in its natural state. Charles Eliot went on to apprentice with landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, design some of the Boston metropolitan park system, and help start The Trustees of Reservations, the world’s first land trust. After his untimely death in 1897, his father took the helm of his late son’s vision and worked with George Dorr to form the Hancock County Trustees of Reservations and acquire properties that became known as Acadia National Park.

Catherine Schmitt is Communications Coordinator for the Maine Sea Grant College Program at the University of Maine.

Catherine Schmitt would like to thank the following for help with research for this article: Wendy Gamble, Pat Lown and Matt Murphy at WoodenBoat Publications, Tim Garrity and the Mt. Desert Island Historical Society, and Maureen Fournier and Brook Minner of Northeast Harbor Library. More on the Champlain Society can be found at http://mdi.mainememory.net/ page/3817/display.html.

Excerpts from the Champlain Society Record of Meetings and Yacht’s Log 1881

Tuesday, July 5 Photograph and text courtesy Mount Desert Island Historical Society

Photograph and text courtesy Mount Desert Island Historical Society

“Sunshine” went down to S.W. Harbor in the afternoon with Rand, Spelman, and C. Eliot. A very strong breeze in the harbor. The crew made many purchases and visited the P.O. Also ordered two fish spears. Spelman carried a gun but shot nothing. Saw a sea pigeon near Greening’s Island. E.L. Rand found 4 or 5 species of flower that were new to the Botany List. Rand (H.L.) & Hubbard spent the afternoon on Robinson’s Mt….

Monday, July 25

Wretched bad weather still. Woods too wet for walking; sky too wet for sailing. Yet the yacht went out for a couple of hours this afternoon and gave Spelman several shots at sea pigeons and Slade a “shoot” at the sound from Greening’s Island. They also picked up a weary Rand who had been on a tramp to Seal Cove via Bass Harbor. The principal occupation on board seems to have been the eating of candy that was left by the lamented Dunbar as a token of his regard for his fellow campers….

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.