David Driskell At Home in Maine

Setting down northern roots

Photographs by Rodney D. Moore

Pine trees such as these depicted in Pines, a 1973 oil on canvas, have a spiritual aspect for Driskell as symbols of eternity.

Maine is among the least diverse states in America—about 95 percent white according to the latest census data—and may not be, as Portland cultural writer Leigh Donaldson has observed, “the first place that comes to mind when thinking of African-American artists.” Yet a number of eminent black artists have found a home—and inspiration—here. Case in point: David Driskell.

Pine trees such as these depicted in Pines, a 1973 oil on canvas, have a spiritual aspect for Driskell as symbols of eternity.

Maine is among the least diverse states in America—about 95 percent white according to the latest census data—and may not be, as Portland cultural writer Leigh Donaldson has observed, “the first place that comes to mind when thinking of African-American artists.” Yet a number of eminent black artists have found a home—and inspiration—here. Case in point: David Driskell.

I met with Driskell on an afternoon in mid-October as the 84-year-old was preparing to decamp from his home in Falmouth, Maine, for his home in Hyattsville, Maryland. The car was full; the caretaker consulted about battening down the hatches; and the brushes put away. The artist, educator, scholar, and authority on African-American art has made this transition nearly every year since he and his wife, Thelma, purchased the property in 1961.

Driskell’s introduction to Maine came in 1953, when he attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. The renowned summer art program had established scholarships at several schools, including Howard University, in Washington, D.C., where Driskell was a junior. One of his professors had convinced him that art was where he belonged (he had been leaning toward history) and subsequently nominated him for the spot at Skowhegan.

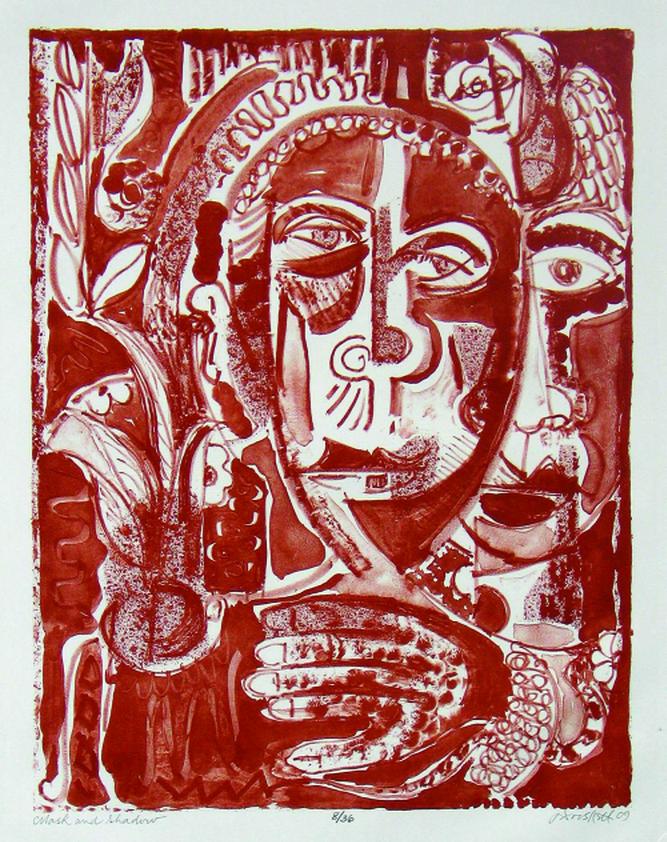

A master printmaker, Driskell often turns to African iconography, including masks, in his work. Mask and Shadow is a 2009 lithograph, 20" x 15 ¾".

For the young painter—Driskell was 22 at the time—Skowhegan was an eye-opener, broadening his sense of the universe of American art.

A master printmaker, Driskell often turns to African iconography, including masks, in his work. Mask and Shadow is a 2009 lithograph, 20" x 15 ¾".

For the young painter—Driskell was 22 at the time—Skowhegan was an eye-opener, broadening his sense of the universe of American art.

There Driskell studied painting with the renowned social realist Jack Levine and with Sidney Simon, one of the school’s founders who would become a well-known sculptor. Marguerite and William Zorach were visiting artists. Classmates included a man named Robert Clark who would later change his last name to Indiana.

That summer, Driskell began painting pine trees, which have remained one of his major subjects. The Maine pines were different from the ones he had grown up with in the small town of Eaton, Georgia, or later in Ellenboro, North Carolina. He loved the way their boughs filtered sun and moonlight; they had a spiritual aspect and became for him symbols of eternity.

Pines also provided Driskell a certain sense of solace during a time of traumatic upheaval in race relations in America. While Driskell made a few paintings related to the notorious murder of Emmet Till, he didn’t feel driven to respond to the unrest in his art. He would play a different role in advancing the rights of his brethren, as an advocate for African-American artists.

The Organ #2, 2005, gouache on paper, 30" x 22". Driskell discovered this vintage instrument at Skowhegan and painted it as part of his “Americana” series.

Like many a Skowhegan student before and after him, Driskell fell in love with Maine. Returning to Howard, he shared his passion with his wife. “You know all famous artists have a summer home in Maine,” he recalls telling her. Others he told about his newfound passion included one of his professors, Nell Sonnemann, at Catholic University of America, where Driskell earned his MFA in 1962. She encouraged him to save his money and buy a place.

The Organ #2, 2005, gouache on paper, 30" x 22". Driskell discovered this vintage instrument at Skowhegan and painted it as part of his “Americana” series.

Like many a Skowhegan student before and after him, Driskell fell in love with Maine. Returning to Howard, he shared his passion with his wife. “You know all famous artists have a summer home in Maine,” he recalls telling her. Others he told about his newfound passion included one of his professors, Nell Sonnemann, at Catholic University of America, where Driskell earned his MFA in 1962. She encouraged him to save his money and buy a place.

Around this time Driskell subscribed to the Christian Science Monitor. In addition to admiring the criticism of Dorothy Adlow—she was among the first mainstream reviewers to cover black artists—he also read the classified ads. One day he found a listing for a two-room “cottage” on six acres of land in Falmouth, Maine, with “electricity, running water, trout brook in the pines.” The last detail, the pines, “got” him.

The cottage turned out to be “hardly a cabin,” but the artist was smitten. After pitching the purchase to Thelma and to a skeptical father (“Maine, that’s Yankee land!” he remembers him saying), Driskell made a down payment.

Now, more than 50 summers later, this place in Maine serves as Driskell’s second studio. The work he does here is a continuation of his work in Maryland and vice-versa—“I paint pines down there, I paint pines up here,” he notes with a laugh. He also makes prints in each place, primarily woodcuts and linocuts.

While he has painted many Maine pines, Driskell has for the most part steered clear of the traditional coastal landscapes. There are exceptions: Maine Island—Iced In, 1973, was painted the winter he taught at Bowdoin College (“They said that was a mild winter; I thought, ‘Oh, my goodness!’”). He also painted on a visit to the home of Eleanor Houston and Lawrence Smith at Wolfe’s Neck Farm in nearby Freeport (he and Smith were on the board together at the American Federation of Arts). And he recalls doing a few “cubistic” sketches while fishing off the Freeport wharf with his daughters in the early days in Maine.

Over the years, Driskell developed a love for vintage rockers and other furnishings, many of which he purchased in Maine. He credits Willard Cummings, a Skowhegan School founder, for encouraging this predilection. He would join Cummings and Hugh Gourley, then director of the Colby College Museum of Art, on antiquing ventures. “Bill had such a good eye,” Driskell recalls. He also became an aficionado of Shaker crafts and remembers with pleasure meeting Sister Mildred, one of the last residents at Sabbathday Lake.

David Driskell’s Falmouth studio is surrounded by trees. Inside, the space is filled with light—and art.

David Driskell’s Falmouth studio is surrounded by trees. Inside, the space is filled with light—and art.

Driskell ended up making paintings of a number of these antiques. Among the most memorable in his ongoing “Americana” series is a wonderful rendering of an organ he first saw as a student at Skowhegan. Returning to the school in 1978 to teach, he was taken by the “almost Baroque” look of the instrument and painted it.

Collage is one of Driskell’s favorite mediums, especially when he mixes it with encaustic and gouache. He loves the hands-on aspect of this technique, which he has used in just about every body of work, including his African mask pieces. He is modest about his accomplishments as an artist: “We work toward creating the ideal, but we don’t reach it in our lifetime,” he stated in the Maine Masters video profile in 2013. “We leave it to somebody else to say, ‘Oh, it’s beautiful.’”

Driskell’s Maine home serves as something of a retreat from his activities as an art historian, teacher (he is Professor Emeritus of Art at the University of Maryland, College Park), lecturer, and advisor to the David Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora in Baltimore. He is the foremost documenter of African-American art, a position that takes him all over the world advising collectors and museums.

Driskell has played a role in Maine art beyond the paintings and prints he has produced here. He helped George Smith establish the MFA degree program at the Maine College of Art. When Anne d’Harnoncourt, director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, fell ill, he delivered her lifetime achievement award tribute to Andrew Wyeth at MECA’s annual honors dinner in 2005. He has also served on the Board of Governors for Skowhegan, which presented him with its Lifetime Legacy Award at its annual gala this past April, one of many honors presented to him by institutions in his adopted state.

The “cottage” in Falmouth has been added onto over the years. Driskell also maintains vegetable and flower gardens, which sometimes provide subject matter for his paintings. And he has planted “memory trees” in honor of friends, including Bill Cummings.

Driskell feels comfortable in Maine. Speaking with former Center for Maine Contemporary Art Curator Bruce Brown in 2006, he noted that a central motive for establishing a home here was so he could “work as I wanted to work and be left alone without having to answer all kinds of questions about race and so forth.” Maine, he has found, “has a welcoming attitude and values its tradition of independence.”

The artist-scholar even credits his home in “Yankee land” with helping his health. “It’s like a refreshing tonic—I dream about it when I’m not here.” Once back in Maryland, he will begin looking ahead to his return to Falmouth, to painting pines and other subjects, in the process reconfirming his place in that line of famous artists who have made their summer homes in Maine.

Carl Little’s most recent book is Jeffery Becton: The Farthest House.

David Driskell is represented by Greenhut Galleries in Portland and D.C. Moore Gallery in New York City.

Related Articles

Share this article:

2023 Maine Boat & Home Show

Join Us for the Maine Boat & Home Show!

Art, Artisans, Food, Fun & Boats, Boats, Boats

August 11 - 13, 2023 | On the waterfront, Rockland, Maine

Click here to pre-order your tickets.

Show is produced by Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine.