Eastport’s new Congregational meetinghouse soon became a Unitarian church, a trend seen throughout New England at the time. In 1854-55 the building was extensively remodeled in the Italianate style by the noted Boston architect Gridley J.F. Bryant. It was destroyed by fire in 1946.

Two groups of Baptists also constructed churches in Eastport around the same time. The First Baptist Society of Eastport erected a large building at the head of Washington Street in 1819. Known as the North Baptist Church and later the North Christian Church, its restrained exterior contrasts with an impressive sanctuary featuring a 23-foot-high vaulted ceiling supported by attenuated classical columns. While the architect has not been identified, the sophistication of the acoustics and the framing system points to someone of Low’s ability. Another prominent local architect-builder, Charles Peavey, served on the building committee, and his sister-in-law contributed $500 toward the cost of construction, factors that make him a likely candidate for designer. Since 2014 the North Church has been owned by the Tides Institute, which has overseen its interior restoration.

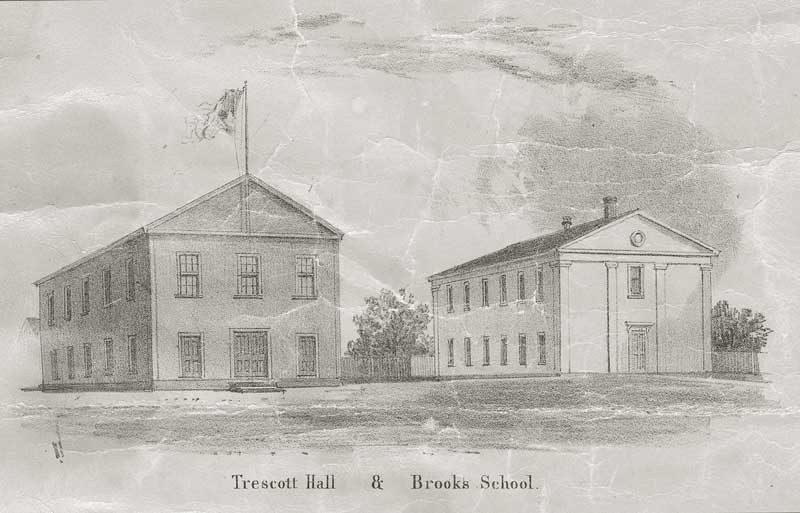

Trescott Hall, left, was built in 1831 by Daniel Low to serve as Eastport’s high school and public hall. At the right is the Brooks School. Both appear in an illustration from an 1855 map of Eastport. Image courtesy Tides Institute

Trescott Hall, left, was built in 1831 by Daniel Low to serve as Eastport’s high school and public hall. At the right is the Brooks School. Both appear in an illustration from an 1855 map of Eastport. Image courtesy Tides Institute

A second Baptist church was built in 1820 by a group of Calvinists. Located on High Street, this meetinghouse was described as “plainly built, without tower or steeple; and the interior was arranged in a peculiar manner, the pulpit standing between the entrance doors, with the congregation seated in the pews facing that way.” This reverse seating plan was used in some Maine churches between 1820 and 1860. When the High Street church was dedicated in November 1820, the Eastport Sentinel of November 18, 1820, described the building as “convenient and neatly finished” and praised “the ingenious architect, Mr. Daniel Low” for its design.

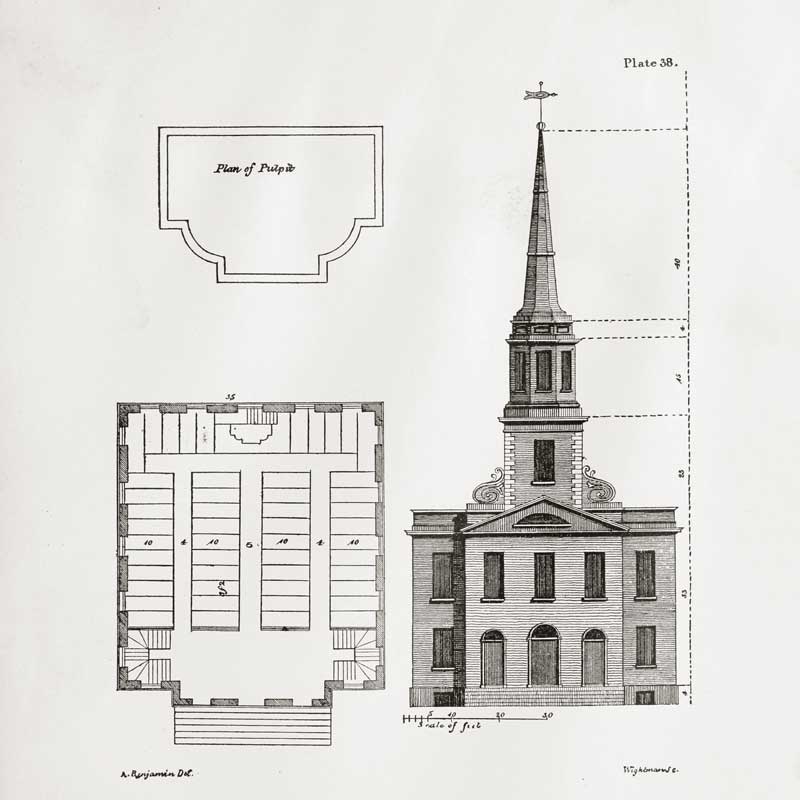

Less than a decade later, Low designed another Eastport Church. The planning for it began in January 1828, when a group of Congregationalists formed the First Evangelical Congregational Church and Society of Eastport, choosing to follow traditional Trinitarian beliefs rather than Unitarianism. They appointed a five-member building committee that included Low, acquired land on Middle Street, and adopted Low’s plan for a handsome Federal-style church. His design called for a symmetrical façade with three entrance bays defined by pilasters that extended from the foundation to the cornice. A pedimented gable contained an elliptical window at its center. A square tower supported an octagonal belfry and spire.

The Bucknam House of 1821 is one of several Eastport residences designed in the Federal style by Low. Photo by Thaddeus Holwonia. Courtesy Tides Institute

The Bucknam House of 1821 is one of several Eastport residences designed in the Federal style by Low. Photo by Thaddeus Holwonia. Courtesy Tides Institute

This design was inspired by Plate 38 of Benjamin’s American Builder’s Companion, of which Low owned the 1806 edition. He looked to Benjamin for the church’s two-story pedimented façade with three arched entrances and elliptical window. However, he broadened its proportions and added attenuated pilasters that foreshadowed the emerging Greek Revival style. True to Benjamin were the square tower with its quoins and the octagonal belfry and spire. Low also followed Benjamin’s recommendations for a spacious interior with pews on the ground floor and galleries on three sides. The focal point of the front wall was a large arch framing the pulpit area.

On July 26, 1828, the Eastport Sentinel wrote this about the unfinished structure: “It is 66 feet by 45, is calculated for galleries and will contain 60 pews. Over the entrance is a vestry room 18 by 45 feet. It was framed under the direction of Mr. Daniel Low in a very neat and workmanlike manner, who is employed to complete this new edifice for the worshipping of the Most High, and whose superior knowledge in architecture we have had occasion to speak of before, he having erected two other temples of worship in this place.”

Across the street from the Bucknam House is the Livermore House, another fine example of Low’s Federal-style residential architecture. Photo by Thaddeus Holwonia. Courtesy Tides Institute

Across the street from the Bucknam House is the Livermore House, another fine example of Low’s Federal-style residential architecture. Photo by Thaddeus Holwonia. Courtesy Tides Institute

The construction of the church progressed rapidly, enabling the dedication to take place in February 1829. In reporting on the ceremony, the Eastport Sentinel praised the new building and its architect: “Considering its size, the house is pronounced by good judges to be well proportioned, to be constructed of good materials, and to be as faithfully put together as any other church in the state. The architecture is beautifully simple.”

In 1830 the Congregationalists reincorporated as the Central Congregational Society of Eastport and sold pews to raise money to complete the building. The following year the parish finished the building with the raising of the spire in June 1831. The Northern Light for June 29, 1831, commented that “the completion of this house adds much to the appearance of the town, and its chaste neatness reflects much credit upon the master builder, Daniel Low, esq., of this town.” Since that time, the Central Congregational Church has remained largely unchanged with two exceptions, the replacement of the belfry and spire in 1869 following their loss in the Saxby Gale and the late-19th-century enclosure of the galleries. The church became the property of the Tides Institute in 2016, but the congregation continues to meet there seasonally.

As the Central Congregational Church spire project reached completion in 1831, Low received a $2,550 commission to plan and construct a two-story frame building for Eastport Academy. Its restrained design of a gable-ended façade with a triangular-pedimented roof line reflects the Greek Revival style. The first story housed a high school with one room for boys and the other for girls. The second floor served as a public hall for dances, lectures, and other community events. The building was named Trescott Hall in memory of a Revolutionary War veteran. It burned in 1881.

While Low is credited with the design and construction of three churches and a public hall in Eastport, much of his work was devoted to building houses. In fact, in some deeds he is referred to as a house carpenter or a housewright. In 1882 Eastport historian William H. Kilby wrote of Low that “many a

substantial old dwelling are monuments of his faithful work.” Two surviving examples of his residential design are the Livermore and Bucknam houses, which face each other at 19 and 20 Key Street. Dating from 1821, these two-and-a-half-story gable roofed homes feature five bay symmetrical facades and restrained Federal-style trim. Behind a later Greek Revival entry on the Livermore House is a Federal doorway with a broad leaded glass fanlight and sidelights. A Federal mantle in a front parlor reflects a sophisticated level of period joinery.

In 1820 Charles Peavey built a substantial Federal-style house for Daniel Kilby at Boynton and Kilby Streets. When Kilby enlarged his home in 1836, he commissioned Low to make a bird house in the form of a church. Its pilastered façade, tower, belfry, and spire recalled Low’s Central Congregational Church, but its pointed arch doorway and windows introduced the Gothic Revival. Describing the martin house as a town landmark in 1893, William Kilby stated that “it was made by Daniel Low, who could build big as well as little meeting houses.”

During the two decades that Low lived in Eastport, he was an active participant in the community. He served the town as a fire warden and as a surveyor of lumber. He was also a member of the Society at Eastport for the Promotion of Temperance, which he helped to found in 1829. In his personal life, he experienced a major change with the death of his wife and his remarriage. On October 27, 1828, Elizabeth Crooker Low died unexpectedly after a brief illness.

Nearly a year later, Low married Lucy King. They started a new family of a boy and two girls, but their time together was brief. Lucy died three years later.

Low continued to work as an architect-builder in Eastport until his death on January 11, 1838. During his career in Eastport, he was described in the press as an “ingenious architect” who possessed “a superior knowledge of architecture” as well as “good taste and practical skill.” His legacy is found in the Central Congregational Church, a major example of Federal-style ecclesiastical architecture in Maine. In a broader sense, his influence has been felt through his library of five different books by Asher Benjamin, one by Abraham Swan, and one by William Pain. Now at Historic Deerfield, these seven volumes were acquired from a Low descendant by the noted New York architect and author Aymar Embury II. In 1917 he published Asher Benjamin, which contained selected plates and text from Low’s copies. In his introduction, Embury wrote, “I purchased them more from curiosity than from any belief that they would be of the enormous practical use they have proven to be.” This pioneering publication was a forerunner of the large number of reprinted period design books now available to all who are interested in historic architecture.

A native of Portland, Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., directed the Maine Historic Preservation Commission from 1976 to 2015 and has served as Maine State

Historian since 2004.