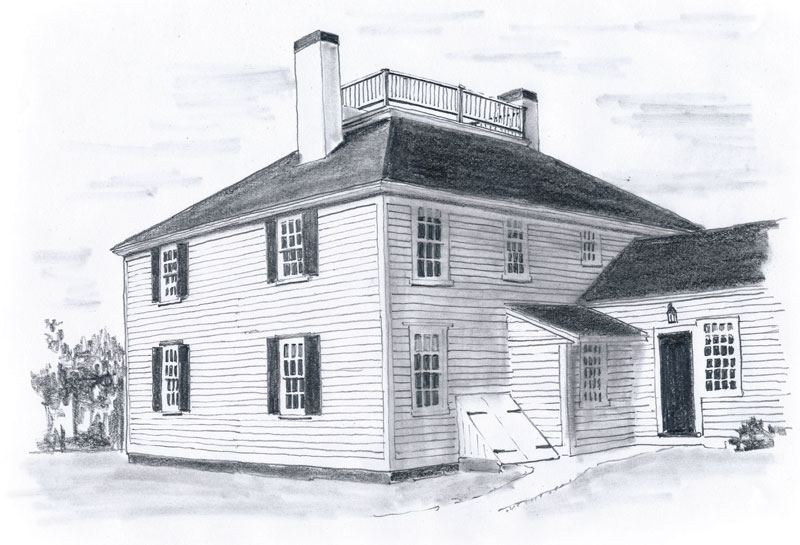

Illustrations by Ted Walsh

Former Maine Governor James Kavanaugh lived most of his adult life in this Federal-style home. His father, also named James Kavanaugh, built this grand, belvedere-topped structure in 1803.

Former Maine Governor James Kavanaugh lived most of his adult life in this Federal-style home. His father, also named James Kavanaugh, built this grand, belvedere-topped structure in 1803.

From the helm or from the street, cupolas are an integral part of the Maine coast. Although these tippy-top architectural appendages are sometimes misunderstood and occasionally misidentified (or mispronounced), they have made a minor comeback in recent years, sometimes for practical or environmental reasons, but often just for nostalgia. And for mariners, they have been of at least passing interest for hundreds of years, as many are marked on paper charts.

“On and off, I’ve been adding them to buildings since I started,” said timber-frame builder John Libby of Freeport. He estimated his company, Houses and Barns by John Libby, has built at least 30 cupolas in more than 40 years of building homes and barns all over coastal and inland New England. In nearly all cases, the cupolas were added either to afford a small viewing room or to provide ventilation.

Likewise, Phil Kaplan of the environmental design firm Kaplan-Thompson Architects in Portland, said cupola-like additions projecting above a home’s ordinary roof line gained popularity in recent years in part because of their natural ventilating and cooling qualities. But these days, “It’s really about the views,” he said of what is now being called a “sky room,” rather than a cupola. “With heat pumps in most new homes today,” he said, “we’re not as dependent on natural ventilation as we had been.”

The cupolas mariners see pinpointed on nautical charts today, with the notation “cup” next to a readily-identifiable bullseye near the shore, were likewise built for a variety of reasons—a view to seaward was often the primary one. Sometimes cartographers mislabeled a roofline projection as a cupola when it was actually what many coastal people call a “widow’s walk.” Widow’s walk is a layman’s term for the architecturally-correct term belvedere, which is a small, uppermost room.

Known as a “widow’s walk,” the fenced-in area at the top of any 19th century home begs the question: Who would build such a structure in anticipation of the untimely death of one’s husband?Even the pronunciation of the word, cupola, seems to have evolved. Variously in Maine, it’s called kyoop-uh-luh, koop-uh-la or cup-ah-la. The word’s 16th century Latin/Italian origins roughly translate as a small “cask” or a “vault.” As the translation implies, a cupola is generally a diminutive architectural appurtenance, often used in Old Europe as a means to see advancing armies long before their arrival. But for anyone who has experienced a real cupola in action on a hot summer day, moving hot air up and out of a building is its most impressive quality. “It can really move a lot of air fast,” said Libby, whose barns often include an active haymow with a cupola to draw out hot air and minimize the danger of fire.

Known as a “widow’s walk,” the fenced-in area at the top of any 19th century home begs the question: Who would build such a structure in anticipation of the untimely death of one’s husband?Even the pronunciation of the word, cupola, seems to have evolved. Variously in Maine, it’s called kyoop-uh-luh, koop-uh-la or cup-ah-la. The word’s 16th century Latin/Italian origins roughly translate as a small “cask” or a “vault.” As the translation implies, a cupola is generally a diminutive architectural appurtenance, often used in Old Europe as a means to see advancing armies long before their arrival. But for anyone who has experienced a real cupola in action on a hot summer day, moving hot air up and out of a building is its most impressive quality. “It can really move a lot of air fast,” said Libby, whose barns often include an active haymow with a cupola to draw out hot air and minimize the danger of fire.

Back on the coast, moving hot air is less of an issue than affording a building’s occupants a commanding view. That’s where the cupola’s larger cousin, the belvedere, comes into play. Some of Maine’s best-known belvederes (sometimes called cupolas) are atop structures such as the James P. White House in Belfast, the James Kavanaugh House at Damariscotta Mills, or even the state governor’s mansion, the Blaine House in Augusta. It’s conceivable all three were originally built to look out toward a bay or downriver for whatever shipping might be arriving. But as is the case with Kaplan’s Portland clients today, they were more likely built for just general viewing—and they look pretty impressive, too.

American cartographers used the term cupola to pinpoint these architectural landmarks on charts primarily to help pre-GPS navigators figure out exactly where they were. Through the use of a navigation method called triangulation, a vessel at sea, across the bay, or down the river could nail down its location by taking bearings on landmarks. In Maine, this was particularly useful when foggy weather might shut out the usual prominent landmarks like lighthouses, and thereby leave mariners with only church spires, cupolas, and prominent chimneys (or factory smokestacks) to use in setting a safe course home.

Efficient and without any carbon footprint, a real cupola on a barn like this, or even a house, will move hot air out and draw cooler air in. And sometimes, nautical charts make note of them for navigation purposes. And the widow’s walk? Depending on which architectural source you read, the term doesn’t show up much until the late 19th century and is generally described as a rooftop platform enclosed by a railing. That makes it an exposed belvedere, which does not seem like a place a successful sea captain would want his family to use while looking for his return from voyages. Nor would it have the venting characteristics of a cupola. But it is definitely a romantic idea with which writers might play and that in itself may have been the origin of the term.

Efficient and without any carbon footprint, a real cupola on a barn like this, or even a house, will move hot air out and draw cooler air in. And sometimes, nautical charts make note of them for navigation purposes. And the widow’s walk? Depending on which architectural source you read, the term doesn’t show up much until the late 19th century and is generally described as a rooftop platform enclosed by a railing. That makes it an exposed belvedere, which does not seem like a place a successful sea captain would want his family to use while looking for his return from voyages. Nor would it have the venting characteristics of a cupola. But it is definitely a romantic idea with which writers might play and that in itself may have been the origin of the term.

Another nautical aspect of the cupola is in its use in the modern boat barn, a new-ish style building to which wooden boat owners often aspire. The structure is essentially a large, open “hangar” without any floor other than well-drained gravel spread over existing soil. Moisture from the gravel floor rises continuously inside the building, keeping a wooden boat from drying out excessively during warm weather. A venting cupola further keeps interior temperatures down significantly, also slowing any drying process and keeping wooden planking from shrinking excessively. I own a barn like this and it has worked like a charm for my wooden boats for years.

Still, despite their modest comeback, modern-day cupolas are unlikely to make it onto future nautical charts—especially since the federal government recently has gone out of the paper chart business. And GPS makes them almost superfluous. But as Kaplan and Libby note, enjoying a view to seaward is unlikely to ever go out of style. So they expect to be adding them to their structures well into the 21st century.

Ken Textor has been living on, working on, writing about, and cruising in boats along the Maine coast since 1977. He lives in Arrowsic.