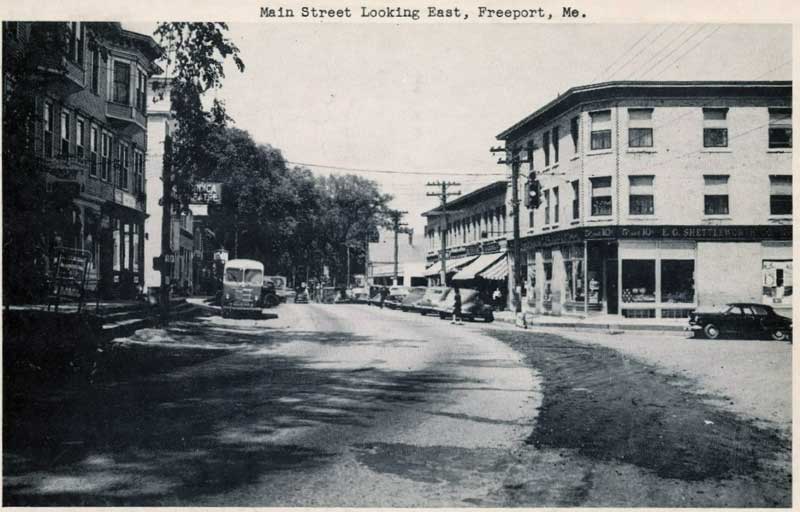

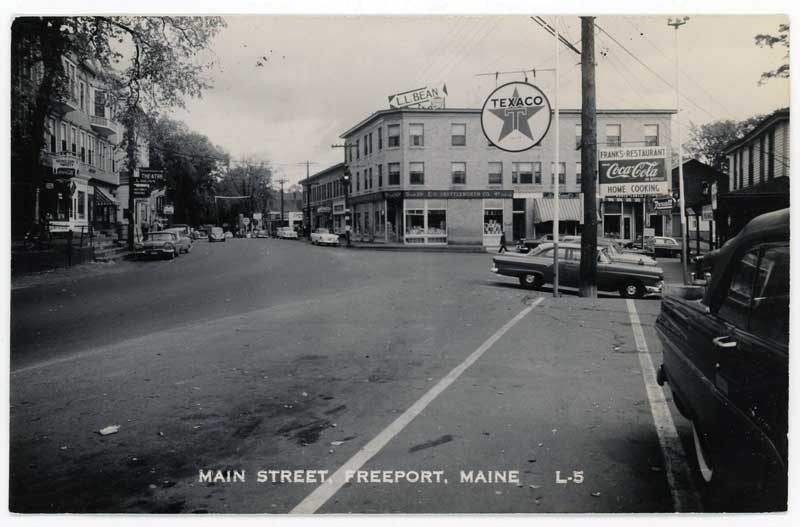

Main Street, Freeport in the 1950s with the Clark Hotel Block at the right displaying L.L. Bean’s rooftop arrow sign. Image courtesy Freeport Historical Society

Main Street, Freeport in the 1950s with the Clark Hotel Block at the right displaying L.L. Bean’s rooftop arrow sign. Image courtesy Freeport Historical Society

Long before outlet stores and boutiques turned Freeport into a Southern Maine tourist destination, outdoor outfitter L.L. Bean and other ambitious merchants, including my father, Earle G. Shettleworth Sr., made the most of a bustling community on the shores of Casco Bay.

Having recently turned 75, I have recollections of the town that extend back three quarters of a century, when I accompanied my father to his store at Main and Bow Streets, a block that’s now home to a Patagonia shop. It’s a glimpse at how things have changed here in Maine, just in one lifetime.

My father was a retailer in Freeport from 1946 until 1968. Born in Middletown, Connecticut, in 1899, he was the youngest of six children of George and Emma Jane Bartlett Shettleworth. My grandfather was an English immigrant who married the daughter of a Connecticut sea captain with New England roots dating back to the 17th century. In 1909, my father began working summers picking potatoes 10 hours a day for 10 cents an hour or a dollar a day. At the age of 15, he moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he worked for the Boston Store and later for the Wisconsin Telephone Company. Returning to Connecticut, he worked for a phone company there, then as an electrician, and enlisted in the US Army Air Corps, though World War I ended before he was called to duty.

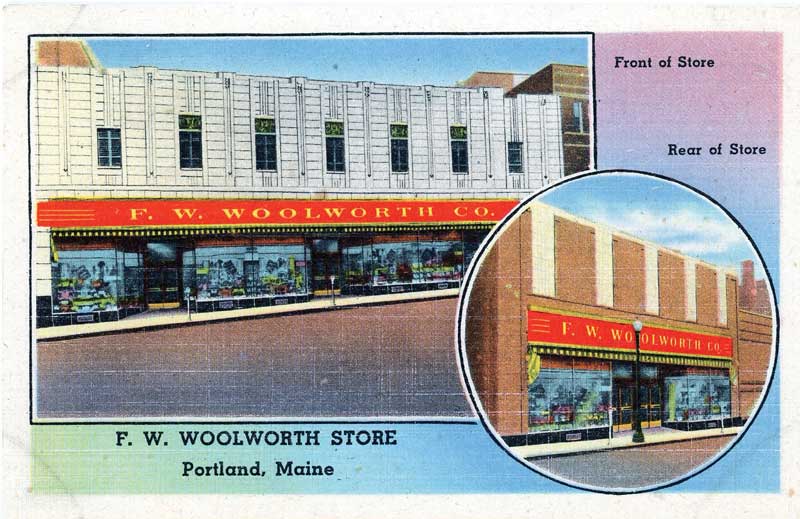

A vintage postcard shows the F.W. Woolworth Store on Congress Street in Portland that Earle G. Shettleworth, Sr. managed from 1933 to 1946. From author’s collection

A vintage postcard shows the F.W. Woolworth Store on Congress Street in Portland that Earle G. Shettleworth, Sr. managed from 1933 to 1946. From author’s collection

It was at the age of 22, in 1921, that my father found his life’s work in retailing by joining the F.W. Woolworth Co. After training in New York City, he managed Woolworth stores in Putnam, Bridgeport, and Hartford, Connecticut; Newport, Rhode Island; Plattsburg, New York; Manchester, New Hampshire; and Portland, Maine. He ran the Portland store on Congress Street, now Reny’s, from 1933 to 1946.

The Portland store prospered during World War II due to the area’s wartime shipbuilding economy, and the company decided to reward my father with a larger out-of-state store. In those days, managers received both a set salary and a percentage of annual sales. However, my parents were settled in Portland with their 3-year-old daughter, Sara, in a beautiful home they had built in the Baxter Boulevard neighborhood in 1940 and ’41. Thus, my father left Woolworth’s in 1946 to manage the frozen food division of Hannaford Brothers.

Working for Hannaford provided the family with an income while my father made plans to open his own store. Surveying the Greater Portland area, he focused on Freeport, a thriving town of 2,800 with six shoe factories and the L.L. Bean sporting goods factory and show room. A prime business location had become available due to the June 5, 1946, fire that swept through Clark’s Hotel at Main and Bow streets. Built in 1910 on the site of the Harraseeket Hotel, the three-story brick Clark Block housed Kimball’s Drug Store and two clothing stores, Gould-Curtis and Small’s, on the first floor. Once hotel rooms, the second and third floors were devoted to apartments and transient rooms.

On October 1, 1946, my father purchased the block from Grace Lugrin of Portland for $32,000, using his own funds and a $12,000 loan from his brother-in-law, Neil Knudsen of Falmouth. Despite post-war building material shortages, he was able to renovate the entire building in time for the December opening of his store in Kimball’s former space to take advantage of the Christmas season. Both clothing stores resumed business in the building, and the restored apartments and rooms were under the management of my father’s sister, Margery, and her husband, Walter Taylor. An experienced carpenter, Taylor was responsible for the maintenance of the building.

Shortly before the opening, Leon Bean crossed Main Street to welcome my father to the Freeport business community. During their conversation, Bean asked about placing a sign on the roof of my father’s building in the form of a large arrow pointing to the L.L. Bean factory and showroom. This sign would guide Route 1 travelers to Bean’s as they entered the Main Street business district.

My father immediately agreed. When Bean inquired about rent for the sign, he assured him there would be no charge, citing the benefit of such advertising for both their stores.

The next day Bean returned with two Hudson Bay blankets for my mother and father in appreciation. Later my father learned that the building’s previous owner had refused a similar request for a sign, and that Bean was especially grateful for the new owner’s permission to install one.

The two men remained friends until Bean’s death in 1967.

At the opening of the E.G. Shettleworth Co. store on December 10, 1946, my father declared, “This is a town with a future, and what’s more, we have a splendid community spirit. I have faith in Freeport.” That day the customers who crowded the aisles found a 5-and-10-cent store on the Woolworth model, with a lunch counter and a wide variety of reasonable priced goods. A daylight basement below the main entrance featured quality second-hand furniture from F.O. Bailey in Portland.

The Six Towns Times published a full report of the opening, saying, “Tuesday morning the E.G. Shettleworth Co. opened its doors for the first time, and a long line of Freeport buyers were already waiting outside for the event. The Shettleworth Co. store is in what used to be the Kimball Pharmacy. In approximately the same location that Kimball had his soda fountain, Mr. Shettleworth has put one in where it will be possible to get light lunches. He will also sell Cushman products at this end of the store. The rest of the store is given over to shelves and counters in the usual large variety store manner, with clerks stationed at counters. The store is brightly lit with fluorescent lighting. In fact, standing outside on the street after dark, the store lights up the square as it has never been lit before.”

The paper also carried several display advertisements relating to the opening. My father’s ad announced, “The Grand Opening of a new variety store with a modern snack bar, homemade ice cream and a Cushman bakery department. You will see many hard-to-get items on display such as enamelware, oil cloth, toilet soap, soap powder, crochet cotton, nylon hose, ladies’ aprons, Turkish towels, tableware, plenty of your favorite candies, toys galore, and a complete line of Christmas wrappings.

Another advertisement extended a warm welcome from local businesses: Baker’s Store, Poulin & Goodwin, Small’s, Freeport Hardware, Ye Green T Kettle, Nordica Theater, L.L. Bean, E.E. Taylor Shoe Co., Jackson Sales, Fish’s Stores, Freeport Grain Company, Gould-Curtis Co., and Six Towns Times.

Beginning about the age of 7, in 1955, I sometimes accompanied my father to his Freeport store on Saturdays. The half-hour journey began on Baxter Boulevard in Portland and followed Route 1 across the Martin’s Point bridge into Falmouth and on through Cumberland and Yarmouth into Freeport. The stretch between Yarmouth and Freeport showed the rise of automobile tourism with its overnight cabins, motels, restaurants, gift shops, and signs for the Desert of Maine. Memorable among these roadside attractions were the Tugboat Restaurant, now the site of the Muddy Rudder, and Clara and John’s Tea Room on the hillside beyond.

As we entered Freeport, Route 1 became the tree-lined Main Street of old homes, culminating in Freeport Square or Post Office Square. The business district was defined by the Patterson Block, the Clark Hotel Block, the Davis Block, the Oxford block, and the Warren Block. The Warren Block housed the post office on the first floor and a staircase leading to the L.L. Bean showroom on the second floor. The rest of the building was devoted to Bean’s factory.

Main Street, Freeport with the Clark Hotel Block at the right in 1947 prior to the installation of L.L. Bean’s rooftop sign. Image courtesy Freeport Historical Society

Main Street, Freeport with the Clark Hotel Block at the right in 1947 prior to the installation of L.L. Bean’s rooftop sign. Image courtesy Freeport Historical Society

As my introduction to retailing began, my father had one rule: the customer is always right and must be treated with courtesy and respect. Such treatment was a key to building customer loyalty and repeat business, he said. My duties were simple. I learned to restock counters and shelves with everything from needles and thread to glassware and dishes. I also assisted the clerks at the cash register to bag or wrap customers’ purchases.

Merchandise was shipped to Freeport by rail. My father and I would drive to the freight depot at the railroad station in his Ford station wagon to pick up arriving cartons and crates. These would be stored in the basement of the store or in the adjacent stable, a relic of the Harraseeket Hotel.

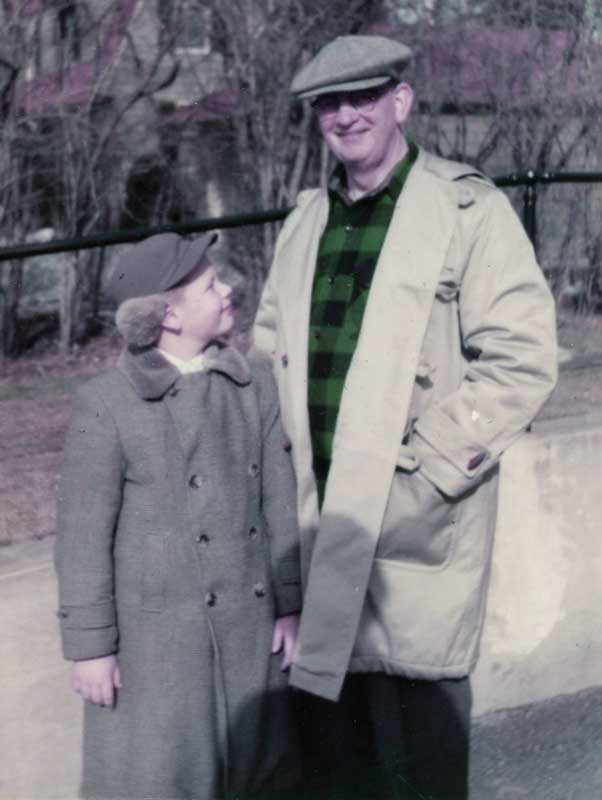

Earle G. Shettleworth Sr. and his son, Earle Jr., often visited Freeport on Saturdays, when Earle Jr. helped out at the store. Image from author’s collectionPromptly at noon, my father and I would cross Main Street to a one-story wooden building next to Bean’s that housed Win Stowell’s restaurant. One large room contained a row of tables and chairs along the left wall, a center aisle, and a lunch counter at the right with an open kitchen behind it. While Freeport had other restaurants such as Frank’s and The Falcon, my father preferred the camaraderie of Stowell’s. Here you could get the great American lunch of a hamburger, fries, and a Coke and rub elbows with attorney Paul Powers, insurance agents Ed Davis and Bill Prindall, and barber Babe Walsh.

Earle G. Shettleworth Sr. and his son, Earle Jr., often visited Freeport on Saturdays, when Earle Jr. helped out at the store. Image from author’s collectionPromptly at noon, my father and I would cross Main Street to a one-story wooden building next to Bean’s that housed Win Stowell’s restaurant. One large room contained a row of tables and chairs along the left wall, a center aisle, and a lunch counter at the right with an open kitchen behind it. While Freeport had other restaurants such as Frank’s and The Falcon, my father preferred the camaraderie of Stowell’s. Here you could get the great American lunch of a hamburger, fries, and a Coke and rub elbows with attorney Paul Powers, insurance agents Ed Davis and Bill Prindall, and barber Babe Walsh.

Sometimes my father planned afternoon visits for me to see Eddie Skilling’s collection of old Freeport photographs or to examine Ray Lydston’s Abraham Lincoln collection. Lydston was a retired printer from Lewiston who lived with his wife and sister-in-law in the second-floor apartment of a house on Upper Main Street. He owned an extensive library of Lincoln books and memorabilia, and once corresponded with the great Lincoln historian Carl Sandburg. He also ran a small business of copying old photographs, which were printed by local photographer Mel Collins.

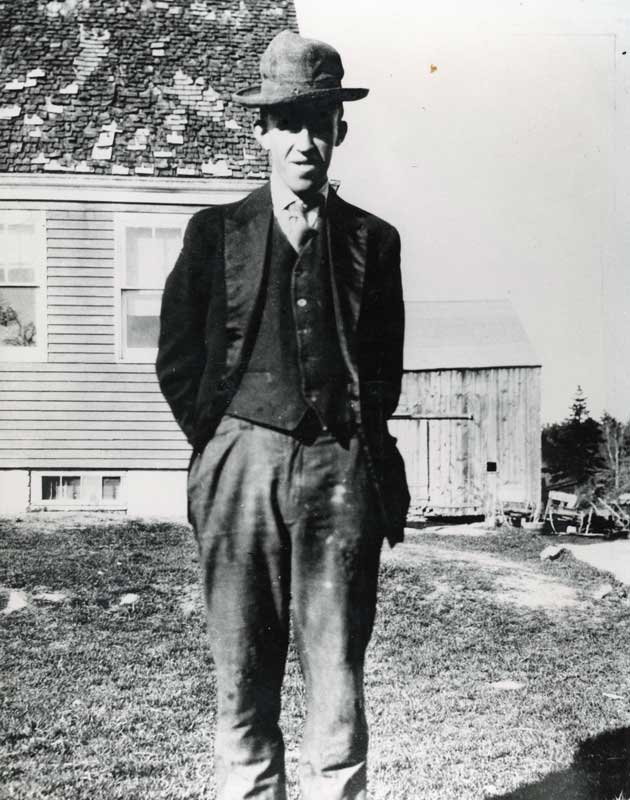

Carroll Jordan was a colorful figure on Freeport’s Main Street in the 1950s. Image from Earle G. Shettleworth Jr.’s collectionIn those days, most small towns in Maine had at least one local character. For Freeport, it was Carroll Jordan. After working in the Bath and South Portland shipyards during World War II, he adopted a relaxed lifestyle of yardwork in the summer and shoveling sidewalks in the winter. Once at Win Stowell’s restaurant, a customer asked Jordon if he was digging a ditch on the property now owned by McDonald’s on Main Street. He replied that he quit the job because he hit rocks, which he was not contracted to move.

Carroll Jordan was a colorful figure on Freeport’s Main Street in the 1950s. Image from Earle G. Shettleworth Jr.’s collectionIn those days, most small towns in Maine had at least one local character. For Freeport, it was Carroll Jordan. After working in the Bath and South Portland shipyards during World War II, he adopted a relaxed lifestyle of yardwork in the summer and shoveling sidewalks in the winter. Once at Win Stowell’s restaurant, a customer asked Jordon if he was digging a ditch on the property now owned by McDonald’s on Main Street. He replied that he quit the job because he hit rocks, which he was not contracted to move.

By the 1950s, Jordan was a tall, gaunt, unshaven figure with one upper tooth and one lower tooth that were revealed by his broad smile. He wore denim overalls in the summer and a union suit under his overalls in the winter. He lived in a small house on his family’s farm in Pownal, and he supplemented his modest income by selling Christmas trees.

Every year my father would arrange to buy a tree. On a Sunday morning in early December, my family and I would visit him in Pownal to select one of his beautiful spruces, which he declared to be “the best in the forest.” He would relate his tall tale of climbing a 40-foot tree, sawing off the top, and falling to the ground with his arms wrapped around his prize.

My father often paid for our Christmas tree twice. Anticipating a tree order, Jordon would ask for an advance during the summer in the form of a razor and shaving cream, a harmonica, or cash for a cold beer on a hot day. By December these advances were forgiven, and my father gave Jordan $20 for a tree as well as a six pack of Budweiser. During these visits, Jordon would display his dry sense of Maine humor by calling me Jack the Giant Killer, because I was tall for my age. He would also share the latest Freeport gossip with my father. On one occasion, he despaired of his friend Henry, whose drinking resulted in him falling asleep under a tree on a winter night. Jordon remarked that if Henry were not careful, he would wake up and find himself dead.

As I grew older, my Saturdays in Freeport became less frequent. By the time I entered junior high school in the fall of 1960, I was collecting old books and photographs. I established a Saturday routine of taking the bus into Portland and spending the day visiting antique shops.

Even with its bustling downtown, on-street parking was still plentiful as compared to today’s downtown Freeport. Image courtesy Freeport Historical SocietyHowever, my ties with Freeport continued. On a warm summer morning in the 1960s, my father and I joined Ed Davis to explore the northern reaches of Casco Bay. The three of us set off from South Freeport in Ed’s lobsterboat. Toward afternoon we sighted the majestic granite tower of Halfway Rock rising from the mist off Harpswell, a dramatic vision that remains fixed in my memory to this day. From Ed we learned that this unexpected landmark marked the halfway point between Portland Harbor and Seguin Island at the mouth of the Kennebec River.

Even with its bustling downtown, on-street parking was still plentiful as compared to today’s downtown Freeport. Image courtesy Freeport Historical SocietyHowever, my ties with Freeport continued. On a warm summer morning in the 1960s, my father and I joined Ed Davis to explore the northern reaches of Casco Bay. The three of us set off from South Freeport in Ed’s lobsterboat. Toward afternoon we sighted the majestic granite tower of Halfway Rock rising from the mist off Harpswell, a dramatic vision that remains fixed in my memory to this day. From Ed we learned that this unexpected landmark marked the halfway point between Portland Harbor and Seguin Island at the mouth of the Kennebec River.

In 1965, Lawrence M. C. and Eleanor Smith learned through my father of my historical interests. That summer they invited me for dinner at the Stone House to show me their impressive collection of ship paintings and their fine library of Maine books, many of which they had acquired from Portland antique book dealer Francis O’Brien. Hanging on a wall was a rare landscape by the early Portland artist Charles Codman. They thoughtfully encouraged me to pursue my passion for the past as I applied to colleges in the coming months.

A Shriners parade passes by Shettleworth’s store on Main Street, Freeport in the 1950s. Image courtesy Freeport Historical SocietySome years later, the Smiths arranged for me to interview Freeport artist Helen Randall, who owned the Freeport Historical Society’s Harrington House on Main Street. The year was 1972; I was in graduate school, and Miss Randall was 87. Both the Smiths and Dr. Charles E. Burden of the Maine Maritime Museum were anxious to preserve Helen’s memories of her sea captain father, Rufus Randall, and his family. Dr. Burden impressed upon me that I would be talking with the daughter of a 19th century Maine sea captain. The result was a 22-page interview that’s now in the files of the museum in Bath.

A Shriners parade passes by Shettleworth’s store on Main Street, Freeport in the 1950s. Image courtesy Freeport Historical SocietySome years later, the Smiths arranged for me to interview Freeport artist Helen Randall, who owned the Freeport Historical Society’s Harrington House on Main Street. The year was 1972; I was in graduate school, and Miss Randall was 87. Both the Smiths and Dr. Charles E. Burden of the Maine Maritime Museum were anxious to preserve Helen’s memories of her sea captain father, Rufus Randall, and his family. Dr. Burden impressed upon me that I would be talking with the daughter of a 19th century Maine sea captain. The result was a 22-page interview that’s now in the files of the museum in Bath.

My father sold the Clark Hotel Block to Paul Powers in February 1956, for $36,700, and leased his space in the building until January 1969. Nearing 70, he announced on January 1, 1969, that he had sold his business to Edgar J. Leighton and his wife Dorothy. Edgar had managed Fish’s store in Freeport and wanted to have his own business. Citing Edgar’s “excellent reputation for trustworthiness and honesty”, my father expressed confidence that the E.G. Shettleworth Co. was in good hands for the future.

The E.G. Shettleworth Co. Store in Freeport was a busy place on opening day, December 10, 1946. Image from author’s collectionMost men would have retired, but my father chose to embark on a new career that he pursued for the next decade. In the 1960s small independent retailers experienced significant competition from large chain discount stores such as Zayre and Kmart. To compete, my father and his business friends formed Cumberland Wholesalers to buy goods in quantity directly from manufacturers, and he became its manager. Partners included former Woolworth managers who had stores in Bridgton, Gorham, Windham, Gray, and Camden. Leighton’s in Freeport was part of this group as well.

The E.G. Shettleworth Co. Store in Freeport was a busy place on opening day, December 10, 1946. Image from author’s collectionMost men would have retired, but my father chose to embark on a new career that he pursued for the next decade. In the 1960s small independent retailers experienced significant competition from large chain discount stores such as Zayre and Kmart. To compete, my father and his business friends formed Cumberland Wholesalers to buy goods in quantity directly from manufacturers, and he became its manager. Partners included former Woolworth managers who had stores in Bridgton, Gorham, Windham, Gray, and Camden. Leighton’s in Freeport was part of this group as well.

After retiring from Cumberland Wholesalers in 1980, my father spent the last years of his life as a salesman, working into his mid-80s selling everything from string to greeting cards. He had a passion for business that was sparked the day he walked into the Woolworth Building in New York City in 1921.

Light lunches were on the menu at the lunch counter in the E.G. Shettleworth Co. Store, and Cushman baked goods were also sold nearby. Image from author’s collection My father lived to see the 1980s transformation of downtown Freeport into a national outlet center, spurred by the reconstruction of the Clark Hotel Block after its September 23, 1981, fire. In the 1950s he and his fellow merchants had debated the pros and cons of the impact of a Freeport bypass on their businesses. Fortunately, they chose to support the I-295 roadway, thereby ensuring a downtown framework for the future instead of a village center bisected by a major highway.

Light lunches were on the menu at the lunch counter in the E.G. Shettleworth Co. Store, and Cushman baked goods were also sold nearby. Image from author’s collection My father lived to see the 1980s transformation of downtown Freeport into a national outlet center, spurred by the reconstruction of the Clark Hotel Block after its September 23, 1981, fire. In the 1950s he and his fellow merchants had debated the pros and cons of the impact of a Freeport bypass on their businesses. Fortunately, they chose to support the I-295 roadway, thereby ensuring a downtown framework for the future instead of a village center bisected by a major highway.

The Freeport of 2023 is now a lifetime away from the Freeport of the 1950s. Here are two more memories of that earlier time, when the bustling post-war downtown was still linked to the past by the weekly visit of a horse and wagon driven by the garbage collector and his wife, who ran a pig farm on the outskirts of Freeport. And on Friday nights, the bright lights of the stores that stayed open until 9 p.m. attracted the shoe shop workers, who received their paychecks that day.

✮

Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr. is the Maine State Historian. This story was adapted from a speech he gave in September, 2023, at the Freeport Historical Society, where his father enrolled him as a charter member in 1969.