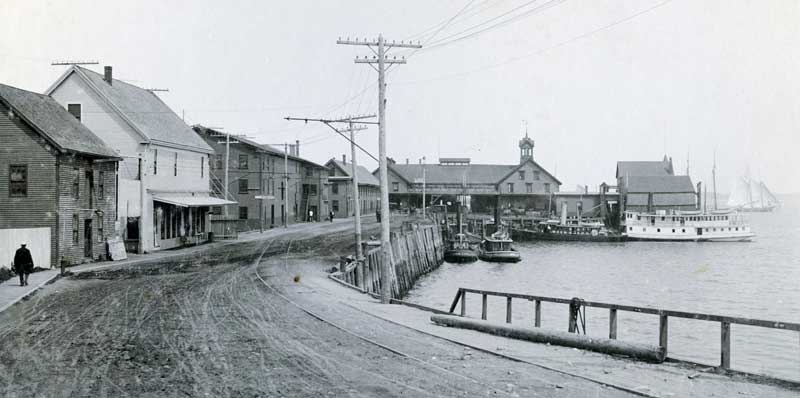

Tillson’s Wharf at the end of Tillson Avenue with the Eastern Steamship Terminal at the end. On the left stand the Simmons White Lobster Co., the Hunter Machine Shop, the Rockland Fish Co., and the Vinalhaven & Rockland Steamboat Co. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

Tillson’s Wharf at the end of Tillson Avenue with the Eastern Steamship Terminal at the end. On the left stand the Simmons White Lobster Co., the Hunter Machine Shop, the Rockland Fish Co., and the Vinalhaven & Rockland Steamboat Co. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

The Point in Rockland, Maine, the L-shaped peninsula stretching out into the harbor along Tillson Avenue and Winter Street, has an industrial aura today, with parking lots, the city’s wastewater treatment plant, a seaweed plant, a Coast Guard base, a marine supply store, a marine canvas company, and a marina and boat repair facility. But in the early 1900s, the Point bustled with activity, with sailors, immigrants, and children. In addition to wharves and fish packing plants, the Point was populated by homes and boardinghouses. Its story should not be forgotten.

Some of the earliest houses in Rockland were built on the Point. There were few roads, travel was by sea, and everyone needed access to a wharf. After an early owner, John Lindsey, cut all the trees off the Point, he used it for a sheep pasture. Then he sold the Point to the Ulmer family; they sold the north leg of the L to the Crocketts, who built houses, stores, wharves, lime kilns, and a shipyard; and they sold small lots for houses, shops, and boardinghouses.

Traders arrived with shiploads of West India goods (sugar, coffee, tea, and fruit) and decided to stay. Other traders arrived with shiploads of English hardware, boots, and fabric and also stayed.

Looking east down Tillson Avenue with the Thorndike Hotel in the left foreground. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

Looking east down Tillson Avenue with the Thorndike Hotel in the left foreground. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

The long narrow farms west of Main Street were subdivided for house lots in 1850, and running water was piped into that area. So, the successful importers, traders, and lime manufacturers built new houses west of Main Street and left the older houses on the Point, with no indoor plumbing, to be rented to poor immigrants.

And they came: Irish and Italians recruited to work in the lime quarries and kilns. The Italians planted beautiful vegetable gardens and apple trees. French Canadians recruited to work in the mills along the rivers, instead came to Rockland and opened restaurants, fished, or built ships. Jews fleeing persecution in Russia came; Finns fleeing impressment in the Russian army came; and Armenians and Albanians fleeing persecution by the Ottoman Empire came. Housing on the Point was cheap, neighbors spoke their languages, and parents looked out for each other’s children.

Civil War General Davis Tillson built Tillson’s Wharf at the end of Sea Street, in 1881, and the Eastern Steamship Company moved its terminal from the Atlantic Wharf in the South End to the end of Tillson’s Wharf. Ferries to the islands left from the wharf, and a fish market and a fish-packing company stood along its side.

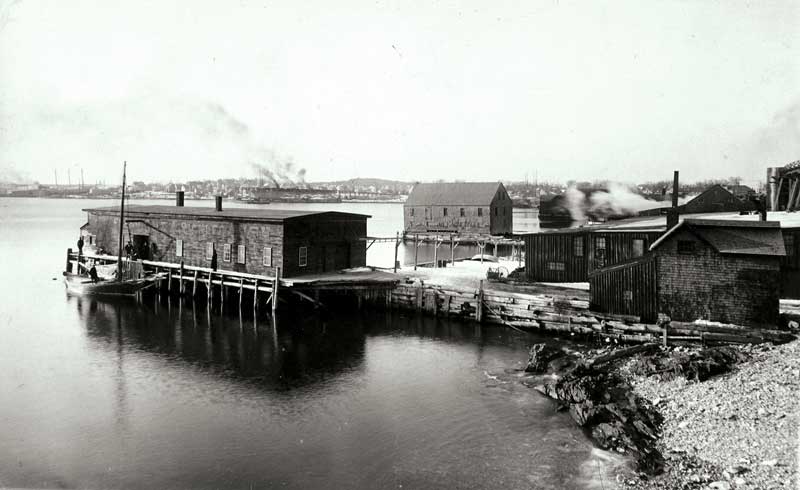

McCloon’s Wharf as it looked in 1900. The wharf is now the site of the Rockland Fish Pier. Note the kilns in the distance on Ocean Street burning lime. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

McCloon’s Wharf as it looked in 1900. The wharf is now the site of the Rockland Fish Pier. Note the kilns in the distance on Ocean Street burning lime. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

Industries came to the Point. The Gas Works operated on Sea Street for 100 years, from 1850 to 1950. The Livingston Manufacturing Company came in 1893 to make tools for the granite industry. Thorndike and Hix built a long wharf in 1893 where they packed lobsters and fish, sold coal and ice, had a slaughterhouse and canning factory, and made barrels. The Morse, Trussell & McLoon Machine Company on Sea Street invented the Knox Marine Engine in 1899, which meant lobstermen could motor out to their traps, instead of rowing. The company became the Rockland Machine Company in 1900 and built an iron foundry and a brass foundry on the Point. At the foot of Winter Street, A.C. McLoon was crating lobsters and selling oil and gasoline for the first automobiles. When the Rockland Rockport Lime Company consolidated its lime kilns in the North End, the Algin Corporation moved to the tip of the Point and began producing carrageenan from seaweed. The Point was an incubator for marine technologies.

East Coast Fisheries dried fish waiting to be shipped to other ports. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

East Coast Fisheries dried fish waiting to be shipped to other ports. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

And there were the fish-packing plants! There were several early plants processing fish. After the turn of the century, North Lubec began canning Eagle Brand sardines. In 1919 East Coast Fisheries merged with Great Eastern Fisheries and packed so much fish they could not distribute it fast enough. They went bankrupt in 1920. One of their new plants became the William Underwood Co. and then was purchased by 40 Fathoms Fisheries, a branch of General Foods, which developed a way to flash freeze fish. F. J. O’Hara processed frozen swordfish and tuna. The Green Island Packing Company processed herring, alewives, mackerel, and sardines, and later was sold to the Port Clyde Packing Co.

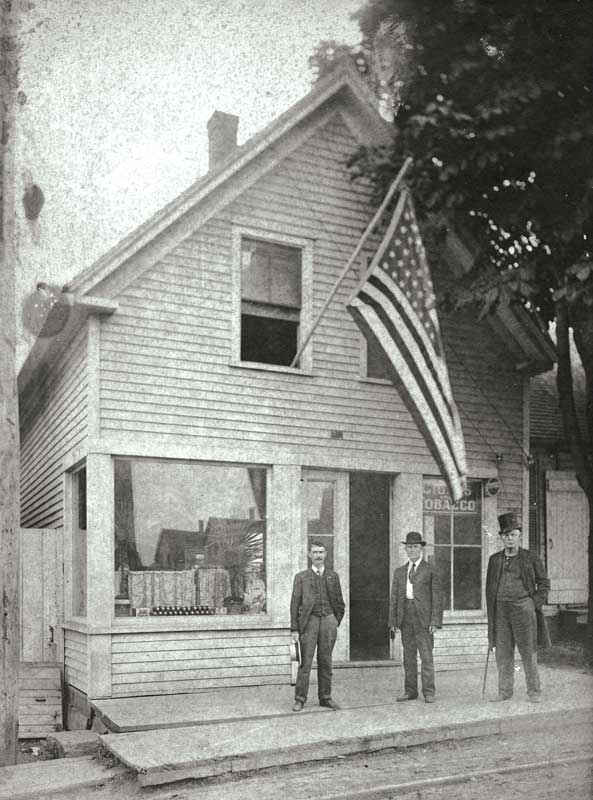

In between the fish-packing plants, the houses, the factories, and the steamboat and shipping wharves were grocery stores, junk stores, a bakery, a candy factory, an ice cream shop, lunchrooms, restaurants, two wholesale grocery businesses, a chicken-processing plant, a hardware and machine shop, a boatbuilding and repair shop, a dance hall and roller-skating rink, boarding houses, bars, stables, carriage houses, and garages, a cigar maker, and one of Rockland’s oldest schools, which later served as a junk shop.

Grocery and Cigar Store on Tillson Avenue near Tillson’s Wharf. Cigars were manufactured here and in many shops in many towns. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

Grocery and Cigar Store on Tillson Avenue near Tillson’s Wharf. Cigars were manufactured here and in many shops in many towns. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

Children played in the fountain that provided water for those families without indoor plumbing. They flew kites and played ball games in the field at the foot of Winter Street. They learned to swim at Crockett’s Beach, which has been filled in where the Landings Restaurant is today. They stopped by the European Bakery where the owner gave them bread because their mothers could not afford to feed them lunch. And they carried spoons in their pockets because the Edwards Ice Cream shop left ice cream in the bottom of the ice cream barrels when those containers went into the dumpster. Children listened for the steam whistles that announced a new shipment of fish arriving at one of the fish-packing plants, and they rushed to the doorway of the plant to watch the fast, rhythmic ballet of cutting fish.

William H. Glover’s Lumber Yard behind buildings on Main Street. Glover’s schooner William H. Jewell sits in Lermond’s Cove. From here it would take lumber to build houses on Islesboro. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

William H. Glover’s Lumber Yard behind buildings on Main Street. Glover’s schooner William H. Jewell sits in Lermond’s Cove. From here it would take lumber to build houses on Islesboro. Photo courtesy Rockland Historical Society

Today the Point is quiet. In 1958, the city removed the public fountain on Tillson Avenue that provided water to many homes, and homes without running water were torn down. In 1975, Lermonds Cove was filled in to provide a parking lot and a site for the wastewater treatment plant, needed to process the raw sewage flowing into the cove from Main Street and beyond. In 1977, the nations of the world extended national sovereignty at sea from three miles to two hundred miles, thus putting the great fishing waters off limits to all but Canada, and the fish-packing plants closed. In 1994, the city passed zoning legislation to promote waterfront industries and prohibit residences on the Point. As the residents left, so did the small businesses. Progress sometimes means loss.

✮

Ann Morris is a historian, author, and curator of the Rockland Historical Society. This article is adapted from her book A History of the Point: The Colorful Past of Rockland, Maine.