This view of the home’s east facade shows an oriel window in zinc-coated copper and the copper bat house just above. One bat house at each end recalls classic dovecotes, but instead of doves welcomes up to 200 bats, naturally contending with mosquitoes who also like to come out at dusk. Photo by Lynn Dube/Wave5 Productions

This view of the home’s east facade shows an oriel window in zinc-coated copper and the copper bat house just above. One bat house at each end recalls classic dovecotes, but instead of doves welcomes up to 200 bats, naturally contending with mosquitoes who also like to come out at dusk. Photo by Lynn Dube/Wave5 Productions

Since designing and building our house in Portland last year, my architect partner and spouse Cynthia Wheelock and I have fielded a number of questions about the process. Our friends want to know how well we worked together, and whether the 1,750-square-foot house and 1,000-square-foot architectural studio met all our ideals.

We designed the house together, working through key decisions by putting forth options and hashing them out until the best idea rose to the top. Sometimes it would take the passage of time, other times, one of us would search for an image from another project to illustrate the concept. In the case of a wood screen wall, once the stair framing was in place the contractor created mock-ups until we settled on the right pattern. In the end, we were able to meet almost all of our objectives. Those that we had to let go—like the Japanese soaking tub and the woodstove—can be added back at a later date.

Without question, the site itself informed the evolution of the building. Taking our cues from nature, and allowing ourselves time for an organic design process, were key. It’s challenging to visualize a house design without knowing the site. In our case, the land included a field that widened and sloped back toward woods and marsh. Since there was not enough space at the front of the lot to build in line with other houses on our street, we set the house envelope farther back, closer to the woods on our 1.6-acre site. The woods adjoin 106 acres of the Fore River Sanctuary, an urban oasis where tributary creeks thread through the marsh. The first time we walked the full length of the site, we saw a gray fox watching us from far below in the wood’s hollow. We took that to be a good sign and decided that we were meant to be here.

The natural wood siding at the entry is sustainably forested Garapa wood. The white trim and punctuation of the blue door evokes memories of the owners’ wooden boats. Photo by Lynn Dube/Wave5 Productions

The natural wood siding at the entry is sustainably forested Garapa wood. The white trim and punctuation of the blue door evokes memories of the owners’ wooden boats. Photo by Lynn Dube/Wave5 Productions

Prolonged design time

Normally, when we design for our clients, we are on a rushed schedule to meet their hopes of breaking ground as soon as possible. For our first ground-up house together, Cynthia and I decided on a slow pace to enjoy the design process. In a period of two years we generated more than 17 design variations. Once these variations coalesced around common themes, the favored design and construction documents came together quickly, in about three months.

Over the course of our planning, we learned about the flora and fauna of our site. We walked, and photographed, and listened to the land with a wildlife botanist, the city arborist, and a native plant expert—each of whom helped us decode the natural elements. The closer the house was to the woods, the closer it came to the animal realm—and we needed to be respectful. One important teaching moment included a warning to leave some fallen trees in place because to remove them would disturb essential habitats.

The challenge was to create the least disruption of the natural habitat with our own new habitation. I remember a story from relatives who built a camp on the Maine coast. It was the first building on this remote site and while they worked on the roof, chipmunks were throwing nuts at them and chattering.

The long side of the house faces true south so that the living spaces face south and west, receiving sunlight all day. A retaining wall anchors the house to the land and creates a sitting wall for a future deck. Photo by Nancy Barba

The long side of the house faces true south so that the living spaces face south and west, receiving sunlight all day. A retaining wall anchors the house to the land and creates a sitting wall for a future deck. Photo by Nancy Barba

Site design

We located the house at the ecotone—writer Terry Tempest Williams describes this transitional zone as vibrant and ever-changing—between a native wildflower meadow providing pastoral relief from the bustle of the street and the bucolic peacefulness of the woods in back. Here we could watch a fox scramble along the understory and hawks soar by at eye level. A jungle of invasive bamboo in the backyard will be replaced with mid-high blueberry bushes—food for butterflies, birds and us humans. Along with newly established native ferns, these bushes will provide cover to some of the smaller species and stabilize a steep embankment. It took time for the animals to reclaim their territory, but within two and a half months after the construction noise stopped, we looked out to see a fox sleuthing along the understory edge.

Perching the house on a small precipice allowed us to embed a full-height lower level into the hillside. By building upward instead of outward, we were able to touch the land lightly, also reducing maintenance and heating costs. We chose electric heat pumps for the heating system. The roof is solar-ready. With future solar panels, the house will be net-zero, and with tree-shading and good cross-ventilation we will be able to avoid the need for air-conditioning.

Oiled wood counters are made from ash, as well as the floors, lending a warmth to the room.Photo by Lynn Dube/Wave5 Productions

Oiled wood counters are made from ash, as well as the floors, lending a warmth to the room.Photo by Lynn Dube/Wave5 Productions

Layout

There’s something wonderful about having one’s bedroom floating in the tree canopy. As long as we are able to walk up the commodious staircase, Cynthia and I will keep the bedrooms on the second floor. There’s a back-up plan for aging in place: either adding a chair lift or converting the screen porch to a master bedroom. Knowing how much we are going to love sitting on the screened porch, I doubt the bedroom location will change anytime soon.

The solar orientation aligned with our desire to angle the house slightly toward the narrow view of the Fore River tributary. The long side of the house faces true south so that the living spaces on the south and west, receiving sunlight all day and benefit from passive heat gain all winter. One of Cynthia’s primary desires was to use some design principles of Vastu Shastra, a traditional Indian system of architecture. As a result the front door faces east where the rising sun shines into the house to start the day.

Light from windows at the top of the stairs filters into the bedroom hall and to a wood screen below, allowing the living space to be naturally lit on all sides. Photo by Lynn Dube/Wave5 Productions

Light from windows at the top of the stairs filters into the bedroom hall and to a wood screen below, allowing the living space to be naturally lit on all sides. Photo by Lynn Dube/Wave5 Productions

Our architecture studio is on the lower level. Because we plan to be here for a long time, we designed this space to be adaptable: architecture studio, in-law apartment, or even a place for our ping-pong table. It has two entrances, one shared and one independent entrance.

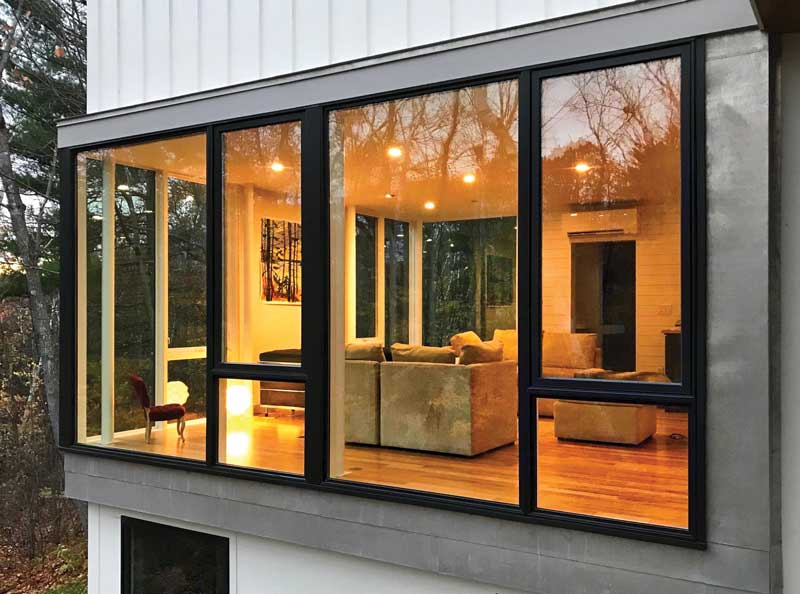

The main approach has a gabled roof, punctuated windows, and nautically-evoked wood detailing. The entry mudroom opens up into a large room with floor-to-ceiling glass framing the forest beyond. This living room floats out over the land, like a ship’s bow, making you feel as if you are being transported via ferry to the islands, leaving the city behind at your back. The room is bathed in sunlight that plays on the off-white walls, with pops of colorful art and objects. We often catch first-time visitors gazing about the room, pausing on details that might have been lost in a more cacophonic space.

Our initial program called for a larger footprint. But it was too big for the site, and too much for us to build and maintain. We opted for multifunctioning spaces: living, dining, kitchen all in one large volume. The washer and dryer are tucked under a built-in sideboard. With a small sink, the sideboard serves as bar, serving counter, flower-arranging area, and extra pantry storage, as well as a laundry. After moving from a late-19th century house with compartmentalized rooms, we are loving the family connection that comes with single-room living, although we do sometimes miss the sound isolation of plaster walls.

One of the two bedrooms upstairs faces the river; the other faces the field. Both are set up to be ensuite master bedrooms with walk-in closets sandwiched between. The staircase on the north side has limited windows, but borrowed light filters into the bedroom hall and to the wood screen below, allowing the living room to be naturally lit on all sides. Our daughter, Eliza, reveled in the design of her own room, setting out a program of all the must-have elements on day one. She stayed involved throughout the lengthy process, visiting the construction site and advising on the color palette, especially the white walls.

A textured wood scrim allows light to filter downstairs from high windows in the stairwell. The sideboard hides a washer and dryer and acts as a serving counter, bar, and for laundry folding. Photo by Lynn Dube/Wave5 Productions

A textured wood scrim allows light to filter downstairs from high windows in the stairwell. The sideboard hides a washer and dryer and acts as a serving counter, bar, and for laundry folding. Photo by Lynn Dube/Wave5 Productions

Construction

For the construction, we selected a family-owned company that primarily builds custom homes of this size. This appeared to be their first house with modern detailing. We were a little uneasy until we recognized the team’s talents, and noticed that they followed our plans and were not afraid to ask for clarifications.

We’d like to think that the construction went quickly and smoothly because we had spent substantial time ironing out details. That’s only part of the truth. The other reason is that the contracting team was well-oiled, working together both within their company and with trusted subcontractors, and hitting nearly all of their milestones. We fit right into the team, supplying missing information on demand and being available at a moment’s notice. We secured our building permit in January, but listened to the contractor and waited to start until March when the ground started to thaw. We moved ourselves into our house in mid-September—less than six months from the start of site work. In April, we moved our office into the studio, just in time to sequester at home.

Speaking to one friend in April, she noted the aptness of our timing and situation: “Your house and studio both in such a wonderful, sacred place? It’s almost as if you designed the house with the pandemic in mind.” It is working out well to have our home and studio all in one place, and to be here to support Eliza as she clicks through her senior year of high school in online learning. It’s even more wonderful that she gets to spend so much quality time solidifying her roots in this place before going off to college in the fall. We are grateful to have a home that we love spending time in, and continue to marvel at the daily occurrence of the skittering of small mammals and aviary delights.

Nancy Barba and Cynthia Wheelock have been practicing architecture together for over 20 years. Their work at Barba + Wheelock Architecture serves a wide array of clients, mostly residential and public work that is poised to affect social change. Stylistically their projects are familiar in form but innovative in design.

Contributors

Star of Hope Project

Barba + Wheelock Architecture and OPAL have been working with the Star of Hope Foundation on its plans to restore the Star of Hope Lodge on Vinalhaven Island. The home, studio, and archives of internationally acclaimed artist Robert Indiana are undergoing a major stabilization project as Phase 1 of the work. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Lodge is possibly one of the most prominent and picturesque buildings along the Vinalhaven waterfront.

The Star of Hope Foundation’s mission is to promote education of the visual arts through various means including exhibitions, a museum arts in residence program, and other endeavors.