Rustic cabins at Lakewood Camps await the angler who seeks to cast a fly to native brook trout and wild landlocked salmon. Photo by Ben Pearson

Rustic cabins at Lakewood Camps await the angler who seeks to cast a fly to native brook trout and wild landlocked salmon. Photo by Ben Pearson

Lighthouses, schooners, and lobsters come to mind when people think of Maine. But there is another side of the state, one featuring the rough-and-tumble currents of large rivers and the sunlit wavelets of vast lakes.

Anglers have been coming to the Rangeley Lakes of western Maine since the 1800s when word spread of the region’s enormous brook trout. Sporting camps were soon constructed to cater to the men and women, who came for the trout, and later, the landlocked salmon that were introduced to the region’s waters near the end of that century.

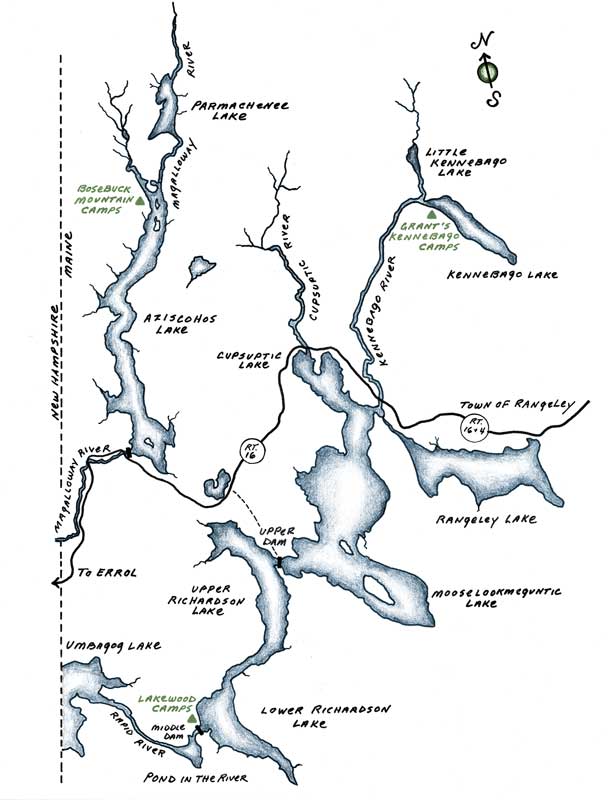

Illustration by Trish Romano

Illustration by Trish Romano

Surrounded by a vast conifer forest, rustic accommodations consisted of a single structure or two that overlooked a lake or pond. It wasn’t long before these rudimentary accommodations evolved into large buildings where “sports” could take their meals and gather around a stone fireplace after a long day on the water. These main lodges were flanked by a series of cabins, each equipped with a woodstove to keep the sports warm as they slept.

Today, these sporting lodges remain much as they were when first built. Upon arriving at Bosebuck Mountain Camps, families will find cabins spread on either side of the dining hall much like in 1919, when Perley Flint first operated the lodge. The seemingly endless view of spruce and balsam stretching down from the mountains surrounding Big Kennebago Lake has not changed much since Ned (Ed) Grant and his sons began building the precursor to what is now Grant’s Camps in the late 1800s. On the same shore as Middle Dam, Lakewood Camps stands as it has since 1893 when Edward Coburn first leased land at the head of the Rapid River. These three sporting camps continue to cater to anglers, who can cast their flies to both brook trout and landlocked salmon—fish that remain as wild as the moose that lumber out of the surrounding forest and the eagles that soar over the pristine rivers and lakes.

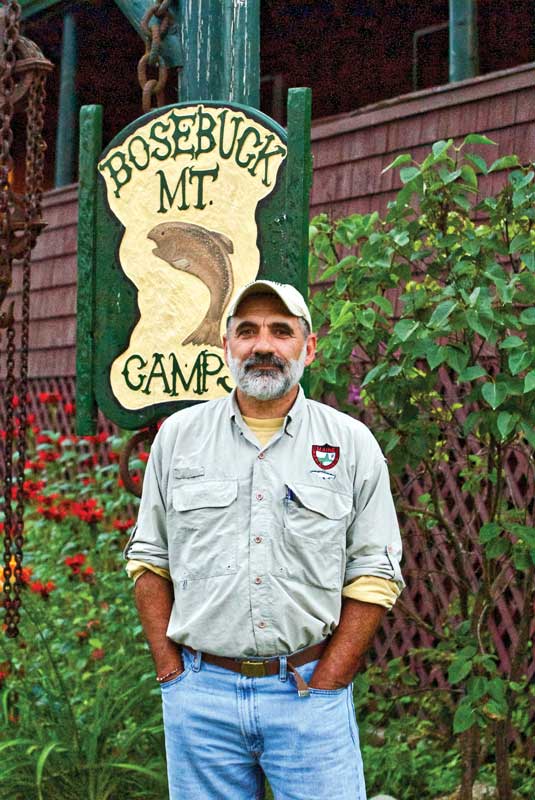

The author outside Bosebuck Mountain Camps. Photo courtesy Trish Romano

The author outside Bosebuck Mountain Camps. Photo courtesy Trish Romano

Bosebuck Mountain Camps

Located at the top of Aziscohos Lake, this sporting lodge overlooks the junction of the Big and Little Magalloway rivers. In the early years, guests were brought by steamboat from the dam at the bottom of the lake up to the lodge. These days, the 13-mile drive to the camp over a dirt and gravel logging road takes 30 minutes.

Guests at Bosebuck are encouraged to unplug. Photo courtesy Trish RomanoBosebuck provides a gateway to a tract of semi-wilderness that contains Parmachenee Lake, as well as the headwaters of the Magalloway River. The forest closes in from both sides as the stream’s serpentine course vacillates between shallow riffles and deep runs with names like Salmon Pool, Cleveland Eddy, Landing Pool, and Little Boy Falls. The river and lake are protected by a series of locked gates that ensure a fishery unsurpassed for the size and number of trout and salmon found there.

Guests at Bosebuck are encouraged to unplug. Photo courtesy Trish RomanoBosebuck provides a gateway to a tract of semi-wilderness that contains Parmachenee Lake, as well as the headwaters of the Magalloway River. The forest closes in from both sides as the stream’s serpentine course vacillates between shallow riffles and deep runs with names like Salmon Pool, Cleveland Eddy, Landing Pool, and Little Boy Falls. The river and lake are protected by a series of locked gates that ensure a fishery unsurpassed for the size and number of trout and salmon found there.

Owned and run by Mike and Wendy Yates, Bosebuck Mountain Camps also caters to hunters, who come for the abundant deer, moose, black bear, grouse, and woodcock. In winter, snowmobilers regularly stop in for a hearty meal and to gas up their machines.

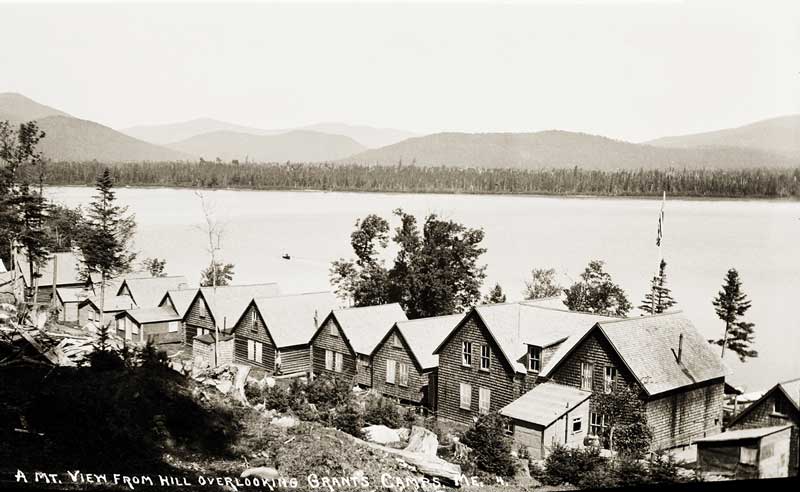

The cabins at Grant’s Camps were built along the shoreline of Big Kennebago Lake at the turn of the century. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

The cabins at Grant’s Camps were built along the shoreline of Big Kennebago Lake at the turn of the century. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Grant’s Camps

Approximately 10 miles east of the dam at the bottom of Aziscohos Lake, the Kennebago River is known for its runs of landlocked salmon and the size of its native brook trout. Like the Magalloway, the river begins its journey as a small brook just south of Maine’s border with Canada. Slipping over cobble, rocks, and larger boulders, it continues for a number of miles before entering Little Kennebago Lake. After exiting the lake, which is little more than a pond, the river winds for another few miles before it enters Big Kennebago Lake. After leaving the larger body of water, the river deepens and widens for more than 12 miles while forming a number of classic salmon pools.

ABOVE: The present-day office at Grant’s Kennebago Camps, where guests experience their first taste of old-fashioned hospitality. Photo courtesy Trish Romano BELOW: Guests at Grant’s Camps stand along the deck of the main lodge in this early 1900s photo. Note the guides standing below and staff standing off to the right. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

ABOVE: The present-day office at Grant’s Kennebago Camps, where guests experience their first taste of old-fashioned hospitality. Photo courtesy Trish Romano BELOW: Guests at Grant’s Camps stand along the deck of the main lodge in this early 1900s photo. Note the guides standing below and staff standing off to the right. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Since the 1970s, John and Carolyn Blunt have owned Grant’s Camps, located nine miles up a logging road off Route 16. John Blunt takes great pride in the history surrounding his sporting lodge. He has not only managed the camps for more than 30 years, but is also a registered Maine Guide, and like any good guide, he will entertain sports with stories of days gone by while putting them on fish, bird, or game.

Much of the river is gated, limiting vehicular access to the lodge’s customers and those owning homes on the big lake that is the largest fly-fishing-only lake east of the Mississippi. Blunt is proud of the many wooden Rangeley boats he has refurbished and maintains for use by his guests. At Grant’s, sports have their choice of fishing the lake or river for a trophy fish or hiking to one of the backwoods ponds.

In the foreground stands Middle Dam, with the Rapid River winding down toward Umbagog Lake, visible in the upper left corner. Photo by Ben Pearson

In the foreground stands Middle Dam, with the Rapid River winding down toward Umbagog Lake, visible in the upper left corner. Photo by Ben Pearson

Lakewood Camps

Of the three lodges, this is the most secluded. Located alongside Middle Dam, this isolated outpost overlooks the western shoreline of Richardson Lake. Water released from the dam forms the Rapid River, named for its turbulent current. Sports can fish the dam’s thunderous release down to Pond-in-the-River. Affectionately called Pondy by the locals, this body of water is approximately a mile long and a mile-and-a-half wide.

The river falls from Pondy for another three or four miles before entering Umbagog Lake. As they have for millennia, fish as large as an angler can imagine continue to lurk in this turbulent combination of treacherous rapids, tremendous boulders, and seemingly bottomless pools. Unlike the Magalloway or the Kennebago, the Rapid can only be accessed by a boat ride across Richardson Lake or by driving over a series of confusing and constantly changing logging roads, and then, only by hiking for over an hour to reach the water.

From the beginning, sportsmen and women have stayed at Lakewood to experience the solitude and tranquility found along the shore of this wild river in a forest spanning over 1,600 acres. Robin Spencer, who recently purchased Lakewood Camps, is committed to preserving this wilderness experience.

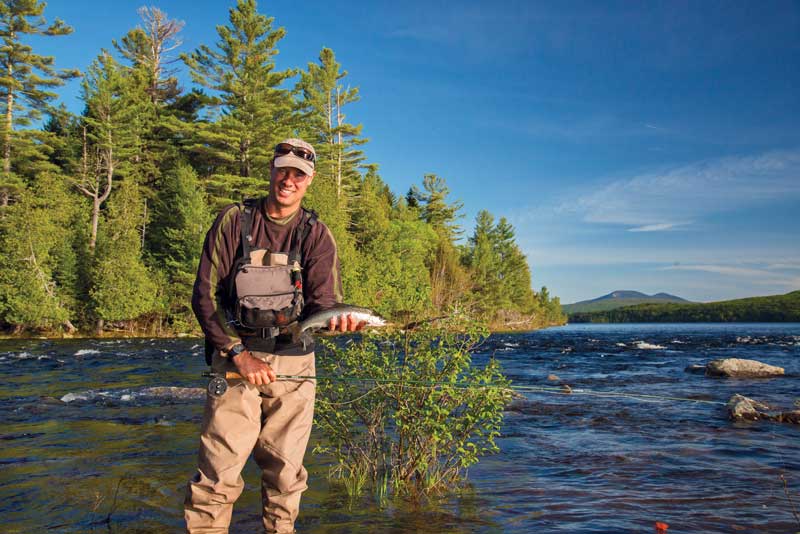

Witness a Maine sporting tradition: A proud angler holds a landlocked salmon along the shoreline of the Rapid River. Photo by Ben Pearson

Witness a Maine sporting tradition: A proud angler holds a landlocked salmon along the shoreline of the Rapid River. Photo by Ben Pearson

Fine fishing, fabulous food, and a rich history

Food served at the three camps is no longer simple fare, with each currently employing a gourmet cook. Although these traditional sporting lodges serve the needs of anglers and hunters, they are family-friendly, catering to anyone, young or old, interested in outdoor activities such as swimming, canoeing, kayaking, hiking, birding, and photography.

The region’s rich sporting history draws many back year after year. While staying at Bosebuck Mountain Camps, you may find yourself casting a fly in the pool once fished by President Eisenhower or hiking a trail trodden by young Johnny Danforth, who while still in his early twenties was one of the first white men to explore the wild country surrounding Parmachenee Lake.

From Grant’s Camps, you can motor a Rangeley boat over to the Logans or Big Sag to try your luck casting a Black Ghost first tied by famous Rangeley taxidermist and painter Herb Welch in 1927 or one of the many patterns created by Carrie Stevens, who from the 1920s through the 1940s perfected the art of tying streamers. In the evening, you can retire to the main lodge and listen to John Blunt tell a tale in much the same way as Ned Grant might have done.

While staying at Lakewood Camps, you can read We Took to the Woods, the first of author Louise Dickinson Rich’s books about her time living along the Rapid River. Afterward, you might walk down the carry road to visit the one-room cabin where the writer spent winters with her husband, Ralph, and their son, Rufus.

Spending time at one of these traditional sporting lodges, you can’t help but feel the presence of those intrepid souls who hiked the same trails, paddled over the same water, and cast their flies into the same pools that remain today.

If you’ve always dreamed of watching a salmon tail dance across the surface of a sun-dappled lake or feeling the pull of a brook trout as it strains your line to the breaking point, if you’d enjoy watching a rainbow frame a conifer hillside after a passing thunderstorm or hearing the haunting cries of a pair of loons under the light of the moon, if you’d like to come home to tell a tall tale like Ned Grant, if you want to be a part of western Maine’s sporting history, then plan to spend a few days at one of the region’s traditional sporting camps.

Robert J. Romano Jr.’s most recent novel, The River King, is set in the Rangeley Lakes Region of western Maine. Visit his website forgottentrout.com for more information.

Plan a sporting camp getaway:

Bosebuck Mountain Camps

Lynchtown, ME

207-670-0013

Grant’s Kennebago Camps

Rangeley, ME

207-864-3608

Lakewood Camps

Andover, ME

207-243-2959