Photos courtesy O’Hara Corporation

In the mid-1800s, Francis Joseph O’Hara left his home in the Irish village of Rush, north of Dublin on the English Channel, signed onto a ship as a cabin boy, and sailed to New York and then Boston. During the Civil War, he enlisted with the Union Navy and was given land in Minnesota as a veteran’s benefit. He traveled back to Ireland to bring his girlfriend to Minnesota. She found it too cold, so they returned to Boston, where O’Hara set himself up as a lobster dealer. Eventually the family landed in Rockland, Maine, and opened a company called F.J. O’Hara.

The O’Haras expanded their business from Boston to Maine in 1939. Here is the F. J. O’Hara & Sons building on Portland’s Union Wharf at that time.

The O’Haras expanded their business from Boston to Maine in 1939. Here is the F. J. O’Hara & Sons building on Portland’s Union Wharf at that time.

From that humble beginning, the O’Hara family has grown their company into a sprawling business with global reach. Headquartered in nondescript buildings on the Rockland, Maine, waterfront, today’s O’Hara Corporation is a classic example of a family-owned company thriving in a world of faceless multinational corporations.

Resilient to the crests and troughs of natural resources, world events, politics, and personal troubles, the company today spans maritime sectors around the world, with three groundfish catcher-processors operating in the Bering Sea off Alaska, two herring boats in Maine, part ownership of the largest scallop fleet in the United States, interest in scallop and finfish processing plants in Massachusetts and China, additional exports to Japan and Korea, a lobster bait dealership, and the popular Journey’s End Marina in Rockland, which includes Maine’s largest indoor boat-storage complex.

Recently, I met with the company’s president and vice president, Frank O’Hara Sr. and Jr., respectively, and with Frank Junior’s son, Casey, a senior staff accountant at the Rockland yard. (Another son, Frank III, is in international sales in the Seattle marketing office. His son Nicholas is the outside yard manager at Journey’s End. A niece also works in the Seattle office.)

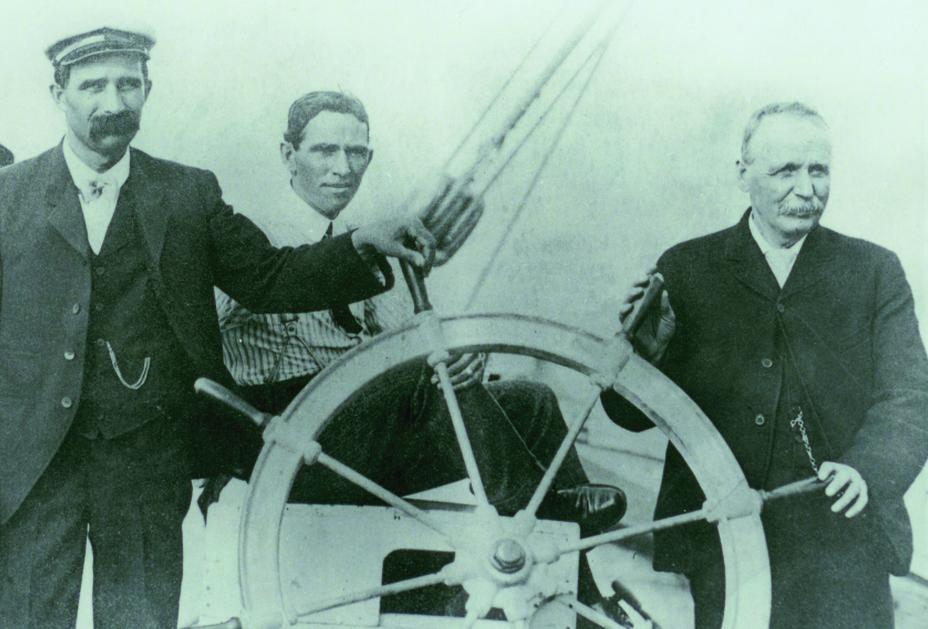

The original Francis J. O’Hara Sr. (far right) sails with his son Francis J. O’Hara Jr. (middle) and a captain (left) on the Francis J. O’Hara Jr., which was built in 1904 and fished for cod, haddock, and halibut on Georges Bank. The namesake of that first Francis, call him Francis II, grew up to work for his father, but wanted more. Francis II borrowed $5,000 (from his father) and, in 1907, formed the Atlantic and Pacific Seafood Company, also on the Boston waterfront. When Francis I closed his company, Francis II adopted the F.J. O’Hara name for his operation and was soon expanding his fishing fleet, starting with a 92-foot wooden schooner, built at Essex Shipyard in New York (and eventually sunk by a German submarine during WWI), followed by seven steel vessels ranging up to 140 feet, built at Bath Iron Works. Defying the Great Depression, O’Hara kept his fleet on the water. One story has it that, when the banks closed down, Francis II needed cash to prepare for a fishing trip so he could keep his business going. His wife got some from her parents, who kept their cash stashed under a mattress because they did not believe in banks.

The original Francis J. O’Hara Sr. (far right) sails with his son Francis J. O’Hara Jr. (middle) and a captain (left) on the Francis J. O’Hara Jr., which was built in 1904 and fished for cod, haddock, and halibut on Georges Bank. The namesake of that first Francis, call him Francis II, grew up to work for his father, but wanted more. Francis II borrowed $5,000 (from his father) and, in 1907, formed the Atlantic and Pacific Seafood Company, also on the Boston waterfront. When Francis I closed his company, Francis II adopted the F.J. O’Hara name for his operation and was soon expanding his fishing fleet, starting with a 92-foot wooden schooner, built at Essex Shipyard in New York (and eventually sunk by a German submarine during WWI), followed by seven steel vessels ranging up to 140 feet, built at Bath Iron Works. Defying the Great Depression, O’Hara kept his fleet on the water. One story has it that, when the banks closed down, Francis II needed cash to prepare for a fishing trip so he could keep his business going. His wife got some from her parents, who kept their cash stashed under a mattress because they did not believe in banks.

Three generations posed at the launching of the company’s newest vessel last summer in Florida. From the left: Frank O’Hara Jr., Frank O’Hara III, Casey O’Hara, Frank O’Hara Sr., and Nicholas O’Hara. “They gave him enough money so he could pay for the ice and salt and grub,” said Frank Junior. “He was the first boat to get out of town, come back, and then sell the fish. That was the big talk of the town.”

Three generations posed at the launching of the company’s newest vessel last summer in Florida. From the left: Frank O’Hara Jr., Frank O’Hara III, Casey O’Hara, Frank O’Hara Sr., and Nicholas O’Hara. “They gave him enough money so he could pay for the ice and salt and grub,” said Frank Junior. “He was the first boat to get out of town, come back, and then sell the fish. That was the big talk of the town.”

In 1939, Francis II expanded operations to Portland, Maine, keeping several boats there and establishing a fish processing plant. He then commissioned the Donaldson Ship Yard in South Portland to build another 10 vessels, making his the largest privately owned fishing company in the country. In a tradition carried on for 30 years, Francis II, a devout Catholic who never drank or swore, named many of the vessels after Catholic colleges such as Holy Cross, Notre Dame, and Georgetown.

During WW II, the company temporarily lost much of its capacity when the U.S. government bought 13 of its 17 new vessels for the war effort. Then came a personal tragedy. One of Francis II’s six children, Dorothy Francis, had a heart condition and the family moved to Palm Beach, Florida, to get her away from the harsh New England climate. Frank Sr., her older brother, recalls his father commuting by train between Maine and Florida. The little girl passed away in 1948.

“Everything changed after Dorothy Francis died,” Frank Sr. said. “My mother collapsed. She didn’t want to be in Florida anymore.”

Frank Sr. was a teenager when the family moved back to Maine. He and his brothers worked summers in Portland for their father at the Portland yard.

Frank O’Hara Sr. is seen here in 1937 at age six christening the 140-foot dragger Villanova, which was built at Bath Iron Works. “One of my father’s expressions, trying to get the three boys to do something—he’d take his hat off, slap a kid and say, ‘Laziness, have I ever offended thee?’” Frank Sr. recalled. “It was priceless.”

Frank O’Hara Sr. is seen here in 1937 at age six christening the 140-foot dragger Villanova, which was built at Bath Iron Works. “One of my father’s expressions, trying to get the three boys to do something—he’d take his hat off, slap a kid and say, ‘Laziness, have I ever offended thee?’” Frank Sr. recalled. “It was priceless.”

After the war, business fell off. Canadian-caught fish flooded the market, and there was little demand for American seafood products. Still, at the urging of a friend, Francis II added a fish-cutting plant in Eastport to his holdings. Frank Sr., having finished prep school and college, went to work there. It was a small operation—a cutting table, a plate freezer, seven or eight cutters. The plant handled herring, lobster, and groundfish, and shipped to Boston and New York.

“It was a struggle to make money there,” recalled Frank Sr.. “It was too far east, and the fish weren’t there like they were in Rockland and Portland.”

In 1954, a year before he died, Francis II consolidated, closing the Boston and Portland operations and moving to Rockland, into a waterfront building that once housed the North Lubec Manufacturing & Canning Co.

Rockland had long been a center for shipbuilding and sardine processing, with dozens of firms employing hundreds of people. O’Hara was located at the center of those activities, with a wharf that could accommodate its own fleet and other fishing vessels. When Frank Sr. eventually shut down the Eastport plant and went to Rockland, he needed to find new markets. So he started fishing for ocean perch, also called redfish, a species well suited to new frozen-food techniques—redfish became a primary protein source for the U.S. military in the 1940s and 1950s, according to NOAA’s Fish Watch.

Business was good and by the 1960s, O’Hara was ready to expand. He commissioned the Harvey Gamage Ship Yard in South Bristol to build two new wooden side-trawlers up to 110 feet long. Over the next decade, he acquired three state-of-the-art steel stern trawlers that fished in the Gulf of Maine where ocean perch was their primary target, along with substantial amounts of groundfish. The plant employed dozens of people to process the product for fresh and frozen shipment along the Eastern seaboard.

In 1978, O’Hara expanded into the scallop industry through a partnership with Roy Enoksen, who owned a New Bedford, Massachusetts-based scallop company. They formed a firm called Eastern Fisheries and explored ways to manage all aspects of the scallop business—from fishing to processing to distribution—in pursuit of broadening their market into Europe and Asia.

Another fleet expansion started in 1979 with construction of five more trawlers. But in 1984, a new international boundary ruling excluded U.S. fishermen from rich fishing grounds off Nova Scotia, on the northeast peak of Georges Bank. In addition, by the mid-1980s, many species of groundfish were in steep decline. O’Hara’s expensive new boats had no place to go.

Like other fishery interests, the company tried to diversify into underutilized Gulf of Maine species—in O’Hara’s case, mackerel, squid, and butterfish. The experiment wasn’t profitable, though.

O’Hara was desperate to keep the company going in the face of shrinking fishing areas and mounting economic pressures. In 1990, he and the principals of several other seafood companies in Massachusetts were accused by the federal government of collaborating to fix prices on frozen seafood sold to the U.S. Department of Defense. The company ended up paying a substantial penalty. By that time, most of the seafood processing plants in Rockland, including O’Hara’s, had closed their doors. Frank Sr. was temporarily out of the picture, but Frank Jr. was now fully involved in the business. The company was down—but not out.

The firm made several crucial decisions to make a strong comeback: they sent fishing boats to the west coast and they got into the pleasure boating market by starting a marina.

First, although the northeast groundfish resource was in serious trouble, the Alaska fishery was doing fine. The O’Haras quickly refitted three of their newest boats as catcher/processors and sent them to Alaska to fish for species such as yellowfin sole, Pacific cod, and Alaska pollock—the latter the most breaded, fast-food fish in America.

Other moves followed. They bought two herring boats and established a lobster bait business to supply midcoast Maine fishermen. And they bought the holdings of National Sea Products, Inc., whose plant was once the third largest fish processor in New England. The purchase gave the firm near-total control of Tillson Avenue’s waterfront end and marked the beginning of a vision that became Journey’s End Marina.

The Enterprise was built at Goudy & Stevens in East Boothbay in 1983 and fished for groundfish out of Rockland. In 1995, she was converted into a catcher-processor in Florida and steamed to Alaska where she currently fishes for groundfish. These moves made the company stronger than ever. The O’Haras bought several more vacant properties to further develop Journey’s End, transforming it from a small marina with crane and boat trailer to a boat transport company with eight trucks and trailers, 50-ton and 75-ton Travelifts, and a huge indoor boat storage facility. The marina absorbed many former packing plant employees and has grown synergistically with the cultural revitalization of the surrounding community.

The Enterprise was built at Goudy & Stevens in East Boothbay in 1983 and fished for groundfish out of Rockland. In 1995, she was converted into a catcher-processor in Florida and steamed to Alaska where she currently fishes for groundfish. These moves made the company stronger than ever. The O’Haras bought several more vacant properties to further develop Journey’s End, transforming it from a small marina with crane and boat trailer to a boat transport company with eight trucks and trailers, 50-ton and 75-ton Travelifts, and a huge indoor boat storage facility. The marina absorbed many former packing plant employees and has grown synergistically with the cultural revitalization of the surrounding community.

O’Hara Lobster Bait is now Maine’s largest bait processor and dealer and also supplies a sizeable frozen storage facility for alternative baits. Since the late 1990s, the company has built or converted eight boats for its Eastern Fisheries scallop fleet, now the largest in the industry, handling about 20 percent of U.S. consumption and selling multi-millions of pounds of scallops in Europe and Asia. Through Eastern Fisheries, the company opened a new processing plant in China and is exploring new trade opportunities in Japan and Korea.

Frank Sr. continues to work as much as he can, and Frank Jr. seems to go non-stop wherever he is—Rockland, Seattle, Alaska, Florida, Asia, Europe. Plans are under way to replace the West Coast boats, each approaching 30 years old. A state-of-the-art catcher-processor, built by Eastern Ship Building in Panama City, Florida, was launched in July and is undergoing interior work. With delivery expected in the spring of 2016, the 194-foot-long craft will have 800 tons of carrying capacity and the latest in ship electronics and processing technologies.

“We can hope that we don’t have continual issues to deal with, but every business does,” Frank Jr. said. “If you don’t change, you have a problem. We’ve always been able to adapt.”

Laurie Schreiber has written for newspapers and magazines on the coast of Maine for more than 20 years.