All photos courtesy Marilyn Moss

Moss and his crew built connected domes on North Haven, including fabric doorway canopies, for a summer house. The walls were made from foamboard panels treated with Teflon.

Moss and his crew built connected domes on North Haven, including fabric doorway canopies, for a summer house. The walls were made from foamboard panels treated with Teflon.

The word home has many meanings: a permanent dwelling place, home plate, homing pigeons, on target, home free, a place to retire, houseboats. What constitutes home to one person may be completely foreign to someone else.

How about a paper home? I would never have imagined living in a paper house and my children playing with paper toys. But that’s the way it was living with Bill Moss, an artist and designer whose creations revolutionized fabric architecture.

Many people know Bill’s name from Moss Tents, the Maine-baed company we formed to manufacture and market his designs for the high-end camping and residential canopy markets. But there is much more to the story. A section of Moss "paper" children's tents and a Parawing displayed at a Ford dealership to promote camping in station wagons.

A section of Moss "paper" children's tents and a Parawing displayed at a Ford dealership to promote camping in station wagons.

My adventure with Bill began not long after he designed and patented the Pop-Tent in 1955. A breakthrough in portable shelter and tent design, the Pop-Tent was the first dome-shaped tent. Freestanding, lightweight, and quick and easy to erect, it reshaped the camping and outdoor recreation landscape—replacing walled tents that had been used previously. Bill designed his curved camping products in bright colors, easily recognizable in campgrounds, because he believed that would attract more women. “Women have taste about product design, utility, and color,” Bill said.

He was right. The cover of the July 14, 1961 issue of Time magazine highlighted the growing popularity of family camping in state and national parks. “This year, 16,500,000 people are headed to the campgrounds—about 2,000,000 more than last year,” the magazine reported.

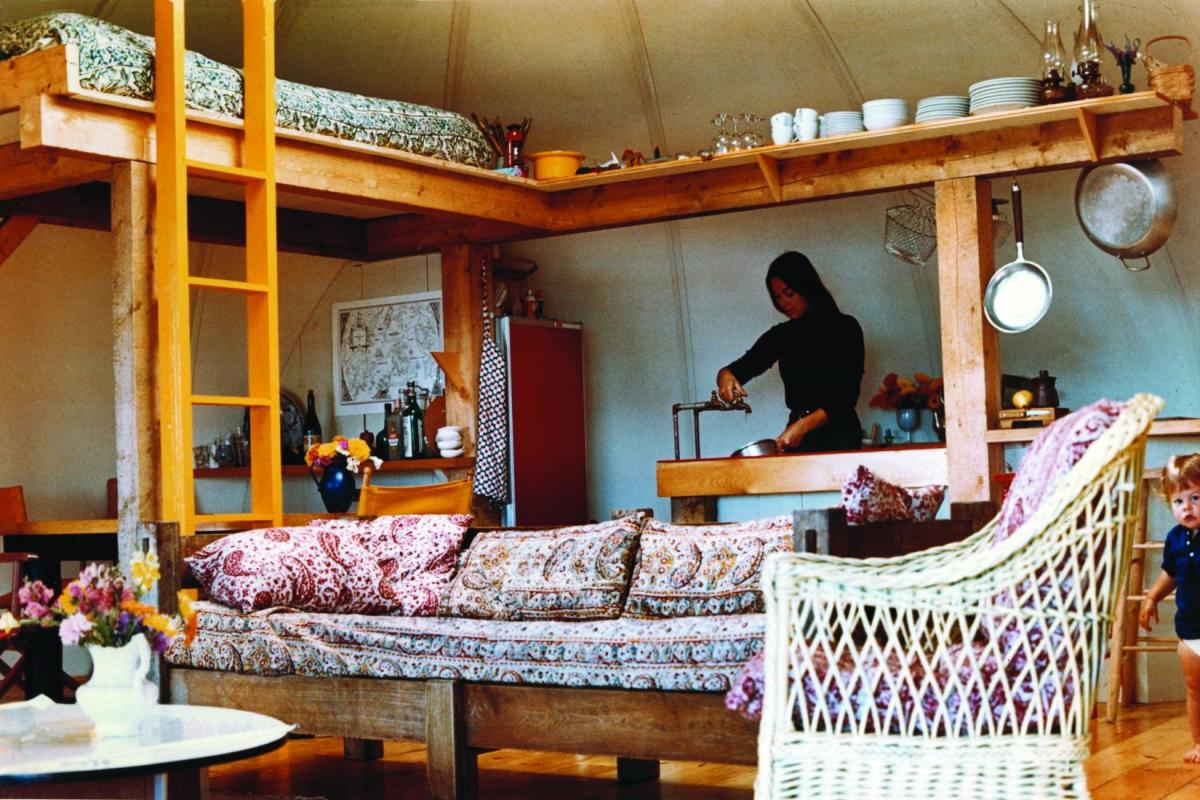

Marilyn Moss works in the kitchen of her North Haven Island dome. The kitchen was small but its “U” configuration worked well for one person to prepare meals, keep track of young children, and participate in conversation with guests.

Marilyn Moss works in the kitchen of her North Haven Island dome. The kitchen was small but its “U” configuration worked well for one person to prepare meals, keep track of young children, and participate in conversation with guests.

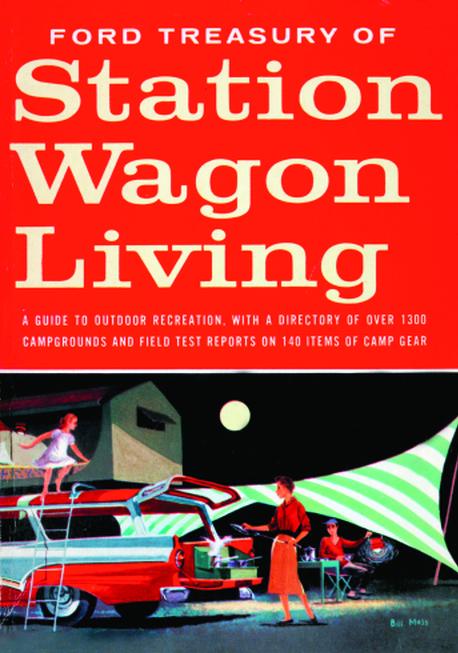

While working at Ford Motor Company as an illustrator for the company’s car owner publication, Ford Times, he and his colleague and fishing buddy, Frank Reck, drove Ford station wagons with their families all over the United States, setting up campsites and testing new and innovative products for the outdoor camping life. They compiled the results of their research into The Ford Treasury of Station Wagon Living, Vols. I and II. Published in 1957, the wildly popular book featured where to find campgrounds, how to pack the car, what to take on trips and how to choose equipment for camping, boating, fishing, and hunting. Volume I of Station Wagon Living by Bill Moss and Frank Reck. The book was filled with information about family camping.

Volume I of Station Wagon Living by Bill Moss and Frank Reck. The book was filled with information about family camping.

Although the outdoors beckoned, families wanted as many conveniences as possible. A promotional unit that Bill designed for a station wagon featured a boat that opened on the top of the vehicle and could be lifted off. Under this, a tent popped up with a sleeping pad for children. A cooking unit slid out onto the tailgate. A fabric canopy, which fanned out from the top of the vehicle, provided shade and light rain protection. Two sleeping pads unfolded in the back of the vehicle for the parents.

In addition to designing the Pop-Tent while at Ford, Bill came up with the idea for what he called the Para-Wing, a hyperbolic paraboloid shade and rain shelter. Previous tarpaulin shelters featured squares of canvas fastened to poles at four corners. The four-sided Para-Wing needed only two poles and four stakes and derived stability from its compound curves and tension. A Wing Tent such as this one was displayed at the 1958 World’s Fair.

A Wing Tent such as this one was displayed at the 1958 World’s Fair.

From this point on, Bill’s creative energies materialized into the creation of shelters for a myriad of uses: from one-person backpacking tents, to larger temporary fabric vacation shelters, to low-cost foam-sprayed housing, to disaster and homeless shelters. He went on to develop tension fabric technology and shake the world of architecture with portable structures that not only redefined notions of shelter and beauty, but also introduced many of the visual forms that we now take for granted.

Ann Arbor, Michigan, during the 1960s was a cradle of experimental performance art and music. Bill and his team embodied this radical exploration by using unconventional materials and construction for products. C. William Moss Associates, our design company, had contracts with Kimberly Clark and Scott Paper Companies. Bill used their product, Kaycel, a spun-bonded paper, to design clothing and tents. He worked with Monsanto’s paper product, Fome-Core, creating toys, dollhouses, birdhouses, doghouses, furniture, and even an ice-fishing shack. Our children’s toys were folding paper Fome-Core animals.

And of course, a paper home inevitably evolved.

A unit that Bill designed for a station wagon featured a boat that opened on the top of the vehicle and could be lifted off. Under this, a tent popped up with a sleeping pad attached for children. A cooking unit slid out onto the tailgate. A fabric canopy, which fanned out from the top of the vehicle provided shade and light rain protection.

A unit that Bill designed for a station wagon featured a boat that opened on the top of the vehicle and could be lifted off. Under this, a tent popped up with a sleeping pad attached for children. A cooking unit slid out onto the tailgate. A fabric canopy, which fanned out from the top of the vehicle provided shade and light rain protection.

In 1968 we installed two “paper” domes on North Haven Island, Maine, as our summer home—actually they were built from Upson foamboard panels coated with Teflon. One 25-foot diameter dome was connected to a 10-foot diameter dome on a 50-foot by 50-foot wooden platform, cantilevered 30-feet high on a steep hill above the shore.  Bill Moss shows off a one-person cardboard shelter for the homeless that he designed.

Bill Moss shows off a one-person cardboard shelter for the homeless that he designed.

Year-round residents of North Haven were skeptical when we erected the “new-fangled paper” habitat, whose dome shape contrasted with the island’s ubiquitous, sharply angled wooden Maine farmhouses. Two large sliding glass doors, inserted into a couple of the dome’s cutout panels, flanked a Franklin fireplace. The glass doors provided a spectacular panoramic view of Penobscot Bay sunsets and the Camden Hills.

My kitchen had a large iron sink, found at the North Haven dump, a small propane four-burner stove and oven, and a small gas refrigerator. Our water was pumped up from a stream. A portable toilet sat outside between the two domes. Gas lights, kerosene lamps and candles provided cozy lighting at night. The domed skylight cap and the two glass doors provided lots of light even on cloudy and rainy days.

Despite the comforts, many islanders didn’t think the structure would last. “The first nor’easter will take her right out to sea,” said one island carpenter who helped us with our deck and flooring. “She” not only outlasted the first nor’easter, but also stood proudly for ten summers and ten harsh Maine winters. Then the material began to fatigue.

The history of portable shelters and tents dates back to prehistoric times. Much later, elaborate Turkish and Persian tents used by royalty had walls woven with intricate patterns, embedded with jewels, resembling the walls of Oriental palaces of the era. The incongruous black tents of the Bedouins, known as the beit al-sha’r or “house of hair,” are loosely woven from sheep and goat hair. One would think black would be too hot for desert use, but as with most things, there is a reason.  A Pop-Tent, left, a Parawing and a Wing Tent.

A Pop-Tent, left, a Parawing and a Wing Tent.

They are beautifully lit inside and, as the outside of the tent gets hot, it causes an updraft that sucks air through the loose weave. If you open the tent flaps, the air comes in, even though there is no breeze. When it rains, the animal hairs swell and the tent gets tight as a drum. Because it’s black, the tent shows no dirt.

When we went to the Middle East in the 1970s to deliver tents to the crowned prince of Abu Dhabi, Bill was inspired by the pole system of the Bedouin tents.

He used the arched pole system in his Event Tent design, as well as other tension architectural structures. Although Bill developed tension fabric technology in 1955 with his Para-Wing, these large tents of the desert were the forerunners of the concept.

Along with designing and developing new camping tents and architectural canopies, Bill also conducted numerous research projects, using unique materials, always trying to create a portable structure from the smallest packaging that could be erected or installed expeditiously.

One such experimental low-cost housing project was the Foam Tent, a large tent of hyperbolic paraboloids made with a Japanese fabric called polyvinyl alcohol. Urethane foam was sprayed onto the fabric from inside the tent. Plastic skylight windows and sliding glass doors were positioned and secured in place by the foam. Then the fabric layer was peeled off, leaving the rigid foam structure.

Here was a shelter that could be built by two men in two days with just a couple of barrels of foam, for less than half the cost of traditional construction. Even before this experiment was completed, sketches of what looked like parachutes were filling up Bill’s sketchbook. These developed into an Airdrop Emergency Shelter System: a nylon dome-shaped structure with fiberglass poles that could be dropped from a plane and would open immediately when it hit the ground.

Bill was very interested in the concept of “instant,” low-cost structures. Another, much later project involved the creation of a cardboard, collapsible pod intended for use by homeless people

living outside on the streets.

Bill’s prophetic work of more than 50 years ago is finally being embraced today. The Pritzker Architecture Prize this year was awarded to an architect whose work includes creating temporary housing out of transient materials like paper tubes and plastic beer crates.

Bill’s lightweight, right-sized structures were forerunners of today’s tiny home movement and its concept of living simply in small homes.

Marilyn Moss is a freelance writer living in Camden, Maine. She most recently published Bill Moss: Fabric Artist & Designer (Chawezi, 2013) and is currently working on her memoir, From the Appalachian Mountains to the Camden Hills. Marilyn is the former president and CEO of Moss Inc. and was married to Bill Moss from 1961-1983.