Boatbuilder Foy Brown and his wife, Louisa, move into their houseboat in Vinalhaven’s Perry’s Creek as soon as the weather is warm enough and stay there until the water starts to freeze. In addition to the houseboat, Foy also built his wooden lobsterboat Centerfold, tied up here to the front porch. Photo by Wayne Hamilton

Boatbuilder Foy Brown and his wife, Louisa, move into their houseboat in Vinalhaven’s Perry’s Creek as soon as the weather is warm enough and stay there until the water starts to freeze. In addition to the houseboat, Foy also built his wooden lobsterboat Centerfold, tied up here to the front porch. Photo by Wayne Hamilton

A mini-movement is springing up along Maine’s shoreline. In an industry renowned for its talent and vision for the production of recreational and working craft, some boatbuilders are taking an old concept—the motorless floating home—and demonstrating their flair for exuberant individuality.

For some, it’s about kicking back and relaxing after a long day at the yard. Others see a new marketing niche—waterborne rentals for seasonal visitors.

An on-demand propane heater, 12-volt pump and water stored in a 50-gallon drum allow for a hot shower. Photos courtesy of Louisa Brown (3)A rustic cottage floating on a back-island creek... talk about a fairy-tale idyll. One almost expects to see Disney butterflies flutter among the colorful medley of potted flowers on the deck.

An on-demand propane heater, 12-volt pump and water stored in a 50-gallon drum allow for a hot shower. Photos courtesy of Louisa Brown (3)A rustic cottage floating on a back-island creek... talk about a fairy-tale idyll. One almost expects to see Disney butterflies flutter among the colorful medley of potted flowers on the deck.

Foy and Louisa Brown of North Haven took about a decade’s worth of sweet time to dream about and build their houseboat, which spends most of its time moored in the protected waters of Vinalhaven’s Perry’s Creek.

“I just saw it in my head,” said Foy. “That’s about the only way I do stuff anyhow.”

Brown’s design method is grounded in solid expertise, though. A lifelong boatbuilder, he’s the co-owner of J.O. Brown & Son, the family-operated boatyard founded in 1888 by his great-great grandfather James Osmond Brown. Louisa worked at the Brown boatyard as a finisher for 13 years; she now runs the North Haven Medical Clinic.

Initially, Brown’s plan was to build two or three floating homes and rent them out. Then he figured the cost of insurance would eat up any profit. The idea of building one for himself stuck, although it took a while to get going. A deck on two sides holds outdoor furnishings, plants and a grill. The house roof overhangs the deck.

A deck on two sides holds outdoor furnishings, plants and a grill. The house roof overhangs the deck.

“I built the float and it was out there on the mooring. I’d go out and do something on it once in a while, then I finally put up the walls, and I had the loft in it, then I kind of forgot about it for a while. Then I got inspired and got the roof on, then I got married, then I got it fixed up pretty nice,” he said, in an inadvertent testament to the power of romance. “The first time we used it was August 14, 2010. We got married that day. That was the celebration.”

The float is constructed with heavy-duty, pressure-treated fir supported by plastic drums. The 12-foot by 20-foot house is regular, stick-frame construction, sheathed with shiplap plywood on the sides and notched pine boards on the ends.

Rigid-foam insulation helps keep the place warm. The interior is sheathed with pine boards set diagonally and finished with white pickling stain (pickling is a technique to work the stain into the wood). A latched barn door completes the woodsy feel.

Foy and Louisa Brown moved into the houseboat on their wedding day four years ago.

Foy and Louisa Brown moved into the houseboat on their wedding day four years ago.Built up to about 20 feet at the peak, the space is divided into a first floor with charmingly unmatched salvaged windows, and a bedroom loft with skylights. Accessed by a ladder, the loft’s open side features a driftwood railing.

“That’s keen,” says Brown. “I just went for a walk and picked up sticks.”

There’s hot and cold running water in the kitchen sink and a propane-fueled refrigerator and stove. An interior partition encloses the head and a small holding tank. Kerosene lanterns and summer-cottage-style furnishings complete the arrangement inside.

During the season—May to October thanks to the insulation—the Browns motor separately to the houseboat from their respective jobs. Louisa gets there about 4 p.m.; Foy, after dark. They read, cook, and gaze at gorgeous sunsets. On rainy days, she knits sweaters. Both are delighted with their summer getaway.

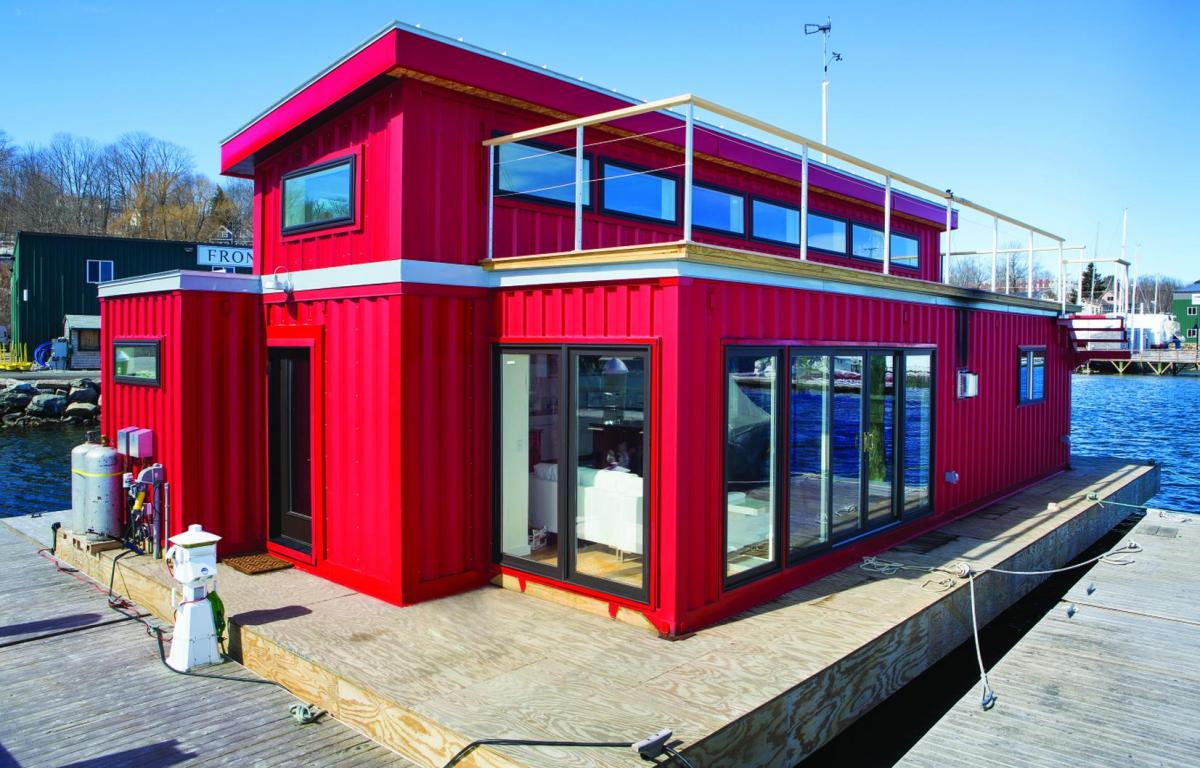

Steve White’s ultra-modern looking houseboat is built from two repurposed shipping containers. He did the design work himself based on other container buildings he had seen. Photos by Billy Black (2)

Steve White’s ultra-modern looking houseboat is built from two repurposed shipping containers. He did the design work himself based on other container buildings he had seen. Photos by Billy Black (2)

“Others have these fancy designers,” says Louisa. “We just did it in our spare time, which is not much—a little hour here and a little hour there.”

Steve White’s houseboat is constructed of two modified shipping containers anchored to a barge and finished to an ultra-modern nicety.

Two years ago, White sold a second house he owned, and wanted to reinvest the money. He looked at waterfront property, then decided to go waterborne instead.

“It just seemed like an interesting approach to get, essentially, a waterfront location for not very much money,” White said.

White is an avid boater and the owner of Brooklin Boat Yard, which was started by his father Joel and produces classic wooden yachts.

“I started working there full-time in 1978, when I finished college,” White recalled. At the time, his father had seven employees. “Now, we’ve got 58.”

Inside, the main living space is fresh and open, lit by clerestory windows and sliding doors.

Inside, the main living space is fresh and open, lit by clerestory windows and sliding doors.

In 2010, White amped up his game when he partnered with several other builders to start Front Street Shipyard in Belfast, which is where he keeps his houseboat.

On a tour, White and I were joined by his partner, Lisa Heidel, and their Bouvier de Flandres dogs, Lucy and Layla. The impressive, red-painted, corrugated-metal structure stands out on the shoreline. The quartet spends weekends there, a getaway from their primary home in Brooklin. Steve White. Photo by Laurie Schreiber

Steve White. Photo by Laurie Schreiber

White was acquainted with the concept of container construction from a couple of angles. About a decade ago, a 12-container house went up not far from his home, its separate units connected by a central, high-ceilinged space. He was also familiar with the portfolio of an outfit based in Brewer, Maine, called SnapSpace Solutions, founded by Chad Walton. Walton had done a powder-coat job for one of White’s boats, but his main passion is container construction as an ecofriendly architectural application. The United States imports more than it exports, which means shipping containers come in loaded with goods, then never leave. Recycled, said Walton, they make dandy modular construction units.

“Whatever we can build with Legos, we can build with these,” he said. “These are hurricane-, tornado-, and earthquake-resistant. They can be stacked 12 to 15 high. You can put them together in blocks of 100 or 200, like a big hotel, and you need only one utility hookup. And we build them super tight and super energy-efficient.”

For White’s purposes, SnapSpace needed perfectly matched, lightly used containers. SnapSpace cut out most of a long side from each, retaining the sections to use elsewhere in the project. Placed opposite each other and separated by an eight-foot-wide corridor, the containers became a sizeable, open-plan living and kitchen area. Openings were cut for doors to a guestroom, master bedroom, bathroom, utility room, and closet, and for windows. The SnapSpace crew reinforced the edges with steel beams, and did the rough plumbing

and wiring, spray-foam insulation, sheetrock, and paint.

The containers were placed on a barge constructed by Brooklin Boat Yard and Baldwin Builders of Sedgwick. Then, using traditional stick-framing techniques, a seven-foot-high addition, comprising exterior walls and a slanted metal roof, was built atop the nine-foot-high containers. The addition includes a sundeck, which is accessed by industrial-style metal stairs. The sections of removed interior walls were used to create the addition’s exterior siding, and the connecting end walls on the main structure below. This enclosed the overall, 40-foot by 24-foot space and made an airy, 16-foot-high ceiling. The whole project took about five months.

The vessel is just as comfortable as any small home, fully equipped with modern appliances and a propane furnace that moves radiant heat through the floor. Freshwater, electric, and septic systems are connected to the municipal supply. Motorless, the houseboat sits all year where it’s tied to the dock, tucked against the shore.

Both Heidel and White are thrilled by the vessel’s promise: It means extra income as a rental during the summer. The rest of the year, it provides them with a getaway in the culturally vibrant city of Belfast, and it’s an eye-catching addition to the waterfront scene.

Then there’s that million-dollar view of the harbor and Penobscot Bay out the big French windows. “That’s the best part,” Heidel said. “Oh, yeah!” Tessie Ann at Robinhood Marine. Courtesy of Robinhood Marine

Tessie Ann at Robinhood Marine. Courtesy of Robinhood Marine

“If it were up to me, I’d never drive over the bridge to Arrowsic. I would just stay here on the island,”Andy Vavolotis said of his digs in Georgetown, where his business, Robinhood Marine, is on a well-protected cove, his house a stone’s throw away.

Love for this pocket of water and the narrow, wooded roads leading here served as inspiration four years ago, when Vavolotis decided to design and build a houseboat. The owner of a thriving marina and service yard, and an energetic guy who’s keen on all things Georgetown- and boat-related, Vavolotis figured there was an untapped customer base that would enjoy the area for the same reasons he did. They just needed a place to stay. What better place than what is, essentially, a floating rental cottage on the water?

Today the yard offers three versions of its Island 40 for rental. Named the Tessie Ann (after Vavolotis’ mother), the Charles Andrew, and the Nancy Lou, these motorless houseboats have the playful styling of miniature tugboats. Two of them have faux smokestacks. (See MBH&H #113, February /March 2011 for a profile of Tessie Ann, the first Island 40.) The layout of the Nancy Lou includes a forward cabin, queen bed, galley, head, and salon that converts into a double bunk. Doors fore and aft lead to a front deck and a rear swim platform. Photo by Melanie Pappastratis

The layout of the Nancy Lou includes a forward cabin, queen bed, galley, head, and salon that converts into a double bunk. Doors fore and aft lead to a front deck and a rear swim platform. Photo by Melanie Pappastratis

“I did a lot of rowing and sailing on small boats in the cove here, and I used to marvel to myself how beautiful this area was, and how it’s an area a lot of people never get to see unless they own a yacht,” Vavolotis recalled. “I said, ‘Geez, you know, maybe we can change that.’”

Vavolotis gave me a tour of the Nancy Lou, a sundeck model. Like a tug, the hull, mounted on pontoons, is utilitarian. Wood-framed, sheathed and decked in marine-grade ply and a fiberglass skin, its sturdy, vertical sides sweep to a rounded bow. The fully insulated, centrally heated house is nothing less than a cottage that happens to have a 360-degree view of the water. The top is an upper deck equipped with rail and bimini. Andy Valvolotis. Photo by Laurie Schreiber

Andy Valvolotis. Photo by Laurie Schreiber

Inside, modern amenities abound—walk-in shower and on-demand hot water, three-burner stove with oven and ventilator, refrigerator, freezer, microwave, sound system—right down to the memory foam mattress and cellphone charger. Propane and solar-charged batteries fuel the appliances.

Vavolotis came to houseboats from a varied boatbuilding background, most notably as the founder of Cape Dory Yachts in 1963.

“From the time I was a little kid, I was driving nails,” he said. “My father had to buy me bags of nails. I was three and I would pound them into everything.”

Robinhood Marine’s three Island 40 houseboats: the Tessie Ann, the Charles Andrew, and the Nancy Lou. Photo by Laurie Schreiber

Robinhood Marine’s three Island 40 houseboats: the Tessie Ann, the Charles Andrew, and the Nancy Lou. Photo by Laurie Schreiber

He grew up in Taunton, Massachusetts, where he built his first boat at age 12. At 16, he built a Class B utility outboard that clocked 50 miles per hour. The sailing bug bit him at 20. Later, he got into carbon fiber and began building high-speed trimarans, a personal hobby.

His career started at Boston Whaler, followed by a detour to real estate.

Sitting unhappily at his real estate office desk, he designed, mainly from instinct, what would become his first Cape Dory, a dinghy. From a start in a shop in a one-car garage, things rapidly advanced. His lines of fiberglass sailboats and powerboats proved wildly popular. By the late 1980s, he owned 140,000 square feet of factory space and had about 325 employees, who turned out thousands of boats.

The 1973 oil crisis got him thinking about fuel efficiency. The yard had just started building commercial fishing boats, so he commissioned naval architect Royal Lowell to design an economically powered displacement dragger.

“We needed a waterfront location to demonstrate one of these boats and have it working, so people would understand what we were doing,” Vavolotis said. Robinhood Marine, a producer of custom yachts since 1950, was on the market. Vavolotis bought the yard in 1981, and ran both outfits concurrently.

Cape Dory Yachts folded in 1992, but Robinhood remained strong. Vavolotis brought up several Cape Dory molds and continued to build. These days, the crew mainly sticks with maintenance and repair. But the houseboat concept was a natural fit.

“I’ve enjoyed this project,” he said. “One doesn’t see it—and I’m not about to say what it is—but a lot of innovation goes into a simple craft like this. I’m proud of that.”

Do we sense a new trend for Maine? Could be. After all, anyone who covets time on our splendid waters will surely love a chance to make themselves right at home.

Laurie Schreiber has written for newspapers and magazines on the coast of Maine for more than 20 years.

An Asian-styled shantyboat

At Front Street, I noticed another eye-catching craft tied up at the dock. Registered as a Sampan 30, this riverboat features multiple curved roofs, and a bright yellow-and-red color scheme set off by the black hull.

“It’s just for fun, something to ghost around in,” said Maynard Haslett, a carpenter at Front Street Shipyard, of his powered riverboat.

Haslett and his wife, Denise Hylton, became intrigued by the concept when they read Harlan Hubbard’s 1953 book Shantyboat: A River Way of Life about drifting down rivers in a scow with a small house on it.

This boat, appropriately named Shanty, was designed by George Davis, another carpenter at the yard who builds boats to live on and travel on from job to job. (Davis described the style of his latest, Wild Pigs, as an Asian sardine carrier.) The two met at the Lyman-Morse Boatbuilding Co. in Thomaston. Haslett, born in Ireland and raised in Massachusetts, arrived at Lyman-Morse after a 20-year career in cabinetry in North Carolina. This brightly colored riverboat is moored in Belfast Harbor. Photo by Denise Hylton

This brightly colored riverboat is moored in Belfast Harbor. Photo by Denise Hylton

“I had a bench right next to George,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Where do you live?’ Davis pointed to a sampan-style boat, named Asylum, tied up to the dock. ‘Right there.’ That’s where it bit me.”

Haslett took me to Shanty. We dropped down to the cockpit and opened the door to a long, narrow cabin containing the essentials for a pleasant skinny-water cruise—galley, bed fitted against the forward bulkhead, small RV-type toilet, camp stove, woodstove, kerosene lantern, hooks for ditty bags.

He picked up a section of plywood sole to reveal supports crafted from white oak lumber that were salvaged from the packaging of shipments of metal siding to the yard. The hull features multiple exterior layers: tar coating sandwiched between fir; ice-and-water shield, typically used on roofs; and treated plywood, caulked with oakum.

The deck consists of two layers of CDX plywood on two-by-four framing, covered with fiberglass mat that was wetted out with vinylester resin and then painted. Structural members for the cabin consist of a mix of salvaged cedar, spruce, and “all sorts of wood” that Haslett picked up over the years. Roll roofing, a hardwood rubrail, old-growth fir sheathing on the inside, store-bought plate-glass windows, and an outboard engine fitted with a long tiller complete the setup.

Haslett and Hylton are planning river cruises, perhaps up the Penobscot to the folk festival in Bangor or meanders to gunkholes downeast.

“It’s our little sanctuary, a space on the water we can rest and get away from the everyday bustle,” said Haslett. —LS

Is it a house or a boat?

In Maine, different towns have different restrictions on houseboats, and some have none at all.

“Most town ordinances restrict houseboats to marinas because they’re basically something that someone is living on,” said Rockland Harbormaster Ed Glaser, who is an officer with the Maine Harbormasters Association. “They have to have a means to pump out the holding tank; they have to have water. So they’re not encouraged in many harbors, although they are allowed in some. They’re also considered to be floats, and there are rules in some towns about having floats on moorings. They have to be registered with U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.”

The question is how to draw the line between a boat that someone is living on for the summer, and a houseboat, he said. If it can be moved, is it a boat? There’s also a difference of opinion on whether houseboats are good or bad. So sometimes the lack of regulation isn’t an oversight. —LS