This installation view of Alex Katz: Gathering at the Guggenheim Museum includes one of the painter’s many portraits of his wife, Ada, at right, and a self-portrait in hat, Passing, 1962-1963, at center, the latter on loan from the Museum of Modern Art. Ariel Ione Williams and Midge Wattles © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

This installation view of Alex Katz: Gathering at the Guggenheim Museum includes one of the painter’s many portraits of his wife, Ada, at right, and a self-portrait in hat, Passing, 1962-1963, at center, the latter on loan from the Museum of Modern Art. Ariel Ione Williams and Midge Wattles © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

In his 95th year, the painter Alex Katz is going full steam ahead. The American art legend is painting like mad, working on a range of new projects, and generally ignoring his age. He is also getting an extra special dose of exhibition heraldry: a retrospective, “Alex Katz: Gathering,” at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City and “Alex Katz: Theater and Dance,” at the Colby College Museum of Art.

Believe it or not, the Guggenheim show is only the second such survey afforded the acclaimed Katz; the other was mounted at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1986. That said, with the artist’s gift of more than 400 of his works to the Colby College Museum of Art in 1992 and the subsequent construction of the Paul J. Schupf wing to house that collection (which now numbers around 900 pieces), you might say Katz enjoys a permanent retrospective, a rare honor for a living artist.

The title of the Guggenheim show is a perfect fit: this “gathering” includes many portraits of family and friends. In addition to paintings of Katz’s wife—and muse—of nearly 65 years, Ada, there are likenesses of a number of writer and painter friends, including John Ashbery, Edwin Denby, Yvonne Jacquette, and Frank O’Hara. The last-named, represented as a free-standing cut-out figure, Katz once called “my hero,” adding “his optimism about being alive is stronger than any poet’s I can think of.”

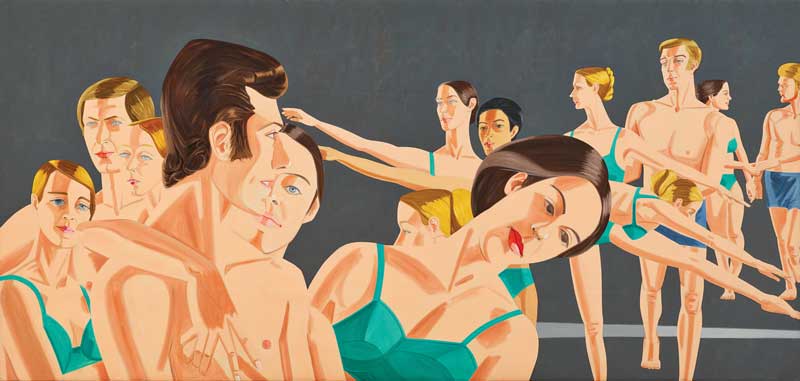

Katz said of his painting Private Domain, 1969, “It’s the first time I really didn’t paint what was in front of me.” Oil on aluminum, 16 x 34 in. © Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY Courtesy Colby College Museum of Art

Katz said of his painting Private Domain, 1969, “It’s the first time I really didn’t paint what was in front of me.” Oil on aluminum, 16 x 34 in. © Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY Courtesy Colby College Museum of Art

Here and there a vision of Maine appears. An early landscape, Lake Time, 1955, conjures a summer day in Lakewood near Skowhegan while Eli at Ducktrap, 1958, offers a portrait of Lois Dodd and Bill King’s young son standing diminutive before a broad coastal prospect.

A more recent work, Crosslight, 2019, relates to Katz’s mission to capture the “initial blast” created by a scene. “I have painted crosslight more than several times,” the artist noted via email. “It is a reaction to what one sees on a summer day when it is really bright out, and the sun’s light crosses the trees, and the tress are dark.” The painting is immersive and nearly entirely abstract.

Meanwhile, to the north in Waterville, “Alex Katz: Theater and Dance” at Colby highlights the painter’s connections to the performing arts. Once again, the museum plays its Katz card to the max, drawing on its expansive holdings plus a number of key loans to mount an exhibition that testifies to the significant role the painter has played in set and costume design for more than half a century.

The idea for the sets and costumes for Sunset started in Madrid, Spain, where Katz encountered a group of young soldiers sitting in a public park, some of them holding hands with girls. Johan Elbers, production photo of Sunset, Paul Taylor Dance Company, 1983. Collection of Paul Taylor. Courtesy Colby College Museum of Art

The idea for the sets and costumes for Sunset started in Madrid, Spain, where Katz encountered a group of young soldiers sitting in a public park, some of them holding hands with girls. Johan Elbers, production photo of Sunset, Paul Taylor Dance Company, 1983. Collection of Paul Taylor. Courtesy Colby College Museum of Art

Asked if there were one performance project that especially pleased him, Katz singled out Sunset, 1983, one of many collaborations with choreographer Paul Taylor (1930-2018). The idea for the sets and costumes, the artist related, started in Madrid, Spain, where he encountered a group of young soldiers sitting in a public park, some of them holding hands with girls. “When we are 18, we have the world in front of us. That was the central idea,” Katz said. In addition to coming up with loon calls for part of the soundtrack, Katz cut off a third of the stage on a diagonal, forcing the dancers to occupy other areas of the proscenium.

In tandem with the fine exhibition catalogue, one should read “The Dance” section of Katz’s autobiography Invented Symbols (1997) where he provides accounts of some of his memorable collaborations with choreographers. Writing about how he wanted to be “offensive, taste-wise,” in his designs for Taylor’s Scuderama (1963), he notes, “It was the first time a set was made to look like a Ramada Inn.”

Katz once stated that Maine light “is richer and darker than the light in Impressionist paintings.” Lake Light, 1992, oil on linen, 66¼ x 78¼ in. Courtesy Sammlung Stiftung Kunst und Natur, Bad Heilbrunn, Germany © 2022 Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Katz once stated that Maine light “is richer and darker than the light in Impressionist paintings.” Lake Light, 1992, oil on linen, 66¼ x 78¼ in. Courtesy Sammlung Stiftung Kunst und Natur, Bad Heilbrunn, Germany © 2022 Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Katz’s autobiography also confirms that he is among the most openly opinionated artists on the planet. He offers thoughts on 30 or so artists, from the ancient Egyptian sculptor Thutmose to Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning. He is fearless and often funny in his appraisals. “I find Rembrandt’s tendency to want to tell stories uninteresting,” he states, while he calls Renoir “one of the premier peach painters.”

When he helped design the layout for the blockbuster “Edward Hopper’s Maine” at the Bowdoin College Museum in 2011, Katz shared some illuminating observations. About Hopper’s light in the painting Road in Maine, 1914, he said, “It’s what it feels like, not what it looks like.” And there was this bon mot: “[Hopper’s] vision is controlling your vision as you look at the painting. It’s a real powerhouse.”

Such commentary helps us understand Katz’s own mission in his art. As someone who once stated, “I love the scale of billboards, the romance of billboards, and the bluntness of them,” he finds strength in scale; some of his canvases fill a good-size wall.

What is this painter advertising? A world, where, in his words, everything is “compressed into a single burst of energy.”

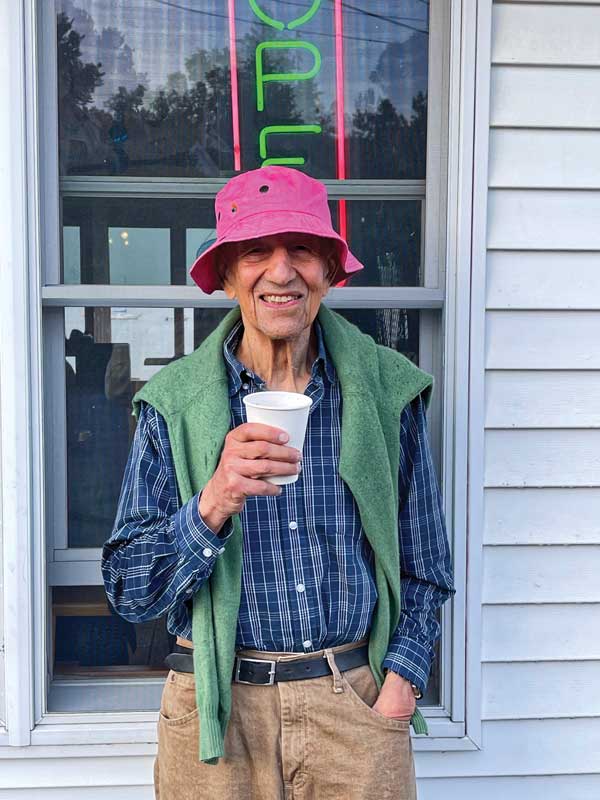

Alex Katz, 2021. © Isaac Katz Courtesy Colby College Museum of ArtIn most biographical accounts of Katz’s life, Maine plays a key role in his development as an artist, starting with his residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in the summers of 1949 and 1950. While he appreciated the training at Cooper Union in New York City, at Skowhegan, he recently recalled, “one had a lot of freedom.”

Alex Katz, 2021. © Isaac Katz Courtesy Colby College Museum of ArtIn most biographical accounts of Katz’s life, Maine plays a key role in his development as an artist, starting with his residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in the summers of 1949 and 1950. While he appreciated the training at Cooper Union in New York City, at Skowhegan, he recently recalled, “one had a lot of freedom.”

Working outdoors enabled him to paint from his unconscious, and this connection, he said, led him to devote his life “to fine art.” It was also the first time he did direct painting “and it was a real kick. It was a blast. It was like feeling lust for the first time.”

In the recent exhibition “At First Light” at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, one of Katz’s Skowhegan paintings was paired with Ashley Bryan’s Skowhegan Pines—an inspired match-up of two New York City-born painters who discovered landscape at the school (Bryan was in the inaugural class of 1946).

Katz’s Skowhegan summers marked his introduction to Maine light, “which is richer and darker than the light in Impressionist paintings,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Being able to see the Maine light helped me separate myself from European painting and find my own eyes.”

After buying a house in Lincolnville in 1954 with Lois Dodd and his first wife Jean Cohen, Katz began his double life: Maine in the summer, New York City the rest of the year. He became part of a lively cohort of artist escapees that found their muse in the midcoast (see “Slab City Rendezvous,” MBH&H, Issue 159).

Today, as he moves from place to place, Katz’s approach shifts. “Maine is almost completely plein air painting,” he noted, “while in New York City I work more with people indoors.” He also brings studies from Maine to Manhattan to work on over the winter: “I can spend six months finishing my summer work.” Both places he finds “visually stimulating.”

Reviewing the Colby College Museum’s Katz holdings, many Maine subjects appear. A partial list includes clam diggers at Ducktrap, various trees and flowers, Lake Wesserunsett, seagulls, canoes, boats, the beach, moose, Lincolnville landscapes, and a cow. Few of these images are wholly representational; “Realism is a variable,” the painter has said.

Longtime Colby Museum director Hugh Gourley (1931-2012) played a key role in bringing the Katz collection to the college. The painter first met him through Willard Cummings, the director of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. “Hugh was an excellent museum director,” the painter recalled: “He listened and paid attention to people and artists.” He credits Gourley with building the college’s museum into a “nationally recognized institution.”

In 2005 Katz launched the Alex Katz Foundation, which is dedicated to supporting up-and-coming and established but underrecognized artists by purchasing and placing their art in public collections. The Colby Museum’s “All in One: Selections from the Alex Katz Foundation Collection” (through June 11, 2023) includes 26 works ranging from three photographs of New York City street scenes by the artist’s close friend Rudy Burckhardt (1914-1999) to a pair of monotypes by contemporary figurative painter Nicole Wittenberg. Katz, who is involved in selecting the work, considers the foundation to be “a way of giving back.”

In considering the “easiness” of Katz’s art, the New York Times critic John Russell once compared the painter to Fred Astaire and Cole Porter. “When it comes to the art that conceals art, Katz is right in there with those two great exemplars,” Russell wrote in his review of Katz’s 1986 retrospective. Some 36 years later, Katz continues to manifest a deceptive effortlessness in his work.

In an interview in The Brooklyn Rail in 2013, artist David Salle asked Katz how he thought a Martian might react to one of his big head paintings. “Ah, I don’t know,” the painter replied. “A Martian might think it’s the greatest thing since toast!” In the same conversation Katz averred that he thought that “intelligence, will, and ambition” were “much more important than talent.” That attitude has served him well.

Carl Little received a lifetime achievement award for art writing from the Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation in 2021.

“Alex Katz: Theater and Dance” at the Colby College Museum of Art runs through February 19, 2023. The museum is also showing “All in One: Selections from the Alex Katz Foundation” through June 11, 2023. “Alex Katz: Gathering” is at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City through February 20, 2023.