All photos courtesy the artist

In Nathaniel Meyer’s painting Under a Swift Sunrise (Monad III), a small spruce-topped, rock-reinforced, slightly tilting island seems to rear up and back from a dark frothing sea. Rounded clouds form an echoing triangle behind the island while the sun sends perfect rays of light into the sky. The scene seems to lie somewhere between reality and legend—an island of the imagination anchored somewhere off the Maine coast.

Another painting, Buyan II refers to a mythical island in Slavic folklore from which, Meyer noted, “all weather emanates.” He happened to be reading about this center of the universe after completing the painting and felt the name was a perfect fit, with the clouds appearing to rise from the tree-clad, rock-bound islet. The Maxfield Parrish-esque palette shores up the magical quality of the image.

Islands are a recurring theme in Meyer’s work—and in his life. He recalled as a child spending the school year at Fort Myers Beach on Estero Island off the Southwest coast of Florida. He also remembered sunny childhood days at his family’s camp on a small island on a downeast Maine pond. The camp, which survived various financial upheavals, remains dear to his heart.

The memory that best illustrates Meyer’s island connections involves the “barely seaworthy” boat his father steered to the rocky archipelago of Frenchman Bay. To a 10-year-old, these trips felt “like dangerous seafaring adventures.” They never knew what mechanical crisis would arise, “nor,” the artist noted, “what treasure we were going to find” when they reached what he describes as magical, self-contained worlds. He likened the journey to painting.

Meyer’s titles are often prompted by such memories. Sunset House, for example, harks back to his early life in Gouldsboro, Maine, where there was a bed and breakfast of that name on Jones Pond. From most points on the water, he recalled, the sun appeared to set in a cleft made by two intersecting ridges. He always thought of that gap as a “sunset house.”

Meyer’s paintings sometimes reference specific places—Wolfe’s Neck, Newell’s Ledge, Schoodic, Monhegan—but they all come from his head even if some of them are “based on a true story.” He relies on memory, “trusting,” he said, “in the impression left behind rather than direct observation or photo references.” Certain places—and paintings—loom large in his mind’s eye and he returns to them often, using these recollections to start a work “and then go where it takes me.”

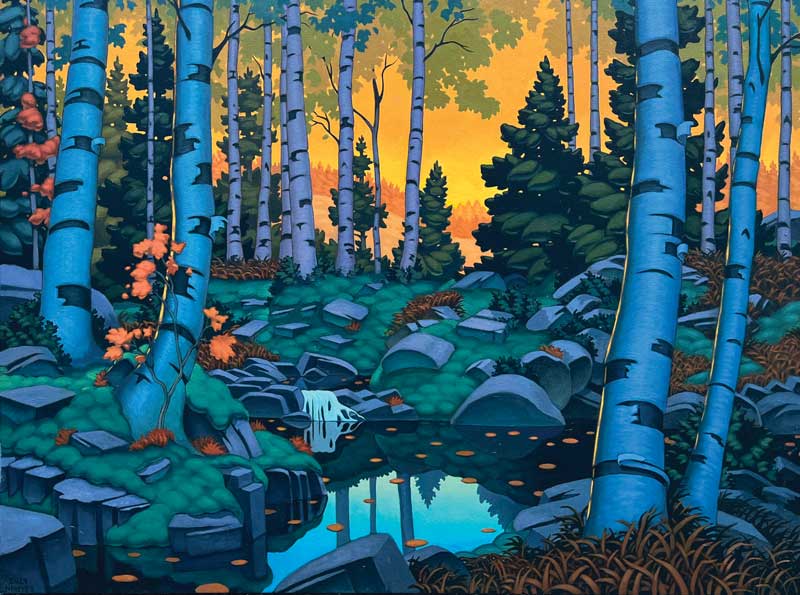

Little Sugarpear Island (after A. J. Casson) reflects Meyer’s love of the landscapes of Canada’s Group of Seven. He is especially drawn to Casson (1898-1992), the youngest member of this celebrated cohort that was active in the 1920s and ’30s. “I think it’s the way he combined precise depictions of the landscape with an exceptional sense of design,” Meyer explained.

Meyer also finds inspiration in the Golden Age illustrators, particularly N. C. Wyeth. He admires Wyeth’s sense of composition and color and the surface quality of his canvases: “He was firing on all cylinders.” He loves how his images “seem to be captured at a perfect frozen moment, on the perfect day, with perfect weather—such a satisfying tableau.” You can see the influence in a painting like Meyer’s Argent Moon, which might be an illustration for a sea-faring tale.

Meyer describes his painting practice as a twofold process: plein air and studio, often starting with the former and ending with the latter. He will head out to explore new ways of translating the landscape into paint, a way to keep his work from “falling into formula,” then return home to turn his discoveries into something fresh.

Meyer’s studio work melds the seen and the invented “to give it a sense of lived-in veracity,” he explained. Starting with a schematic drawing, either in mechanical pencil on Bristol board or on a tablet, he uses the sketches to create a general composition. A simple underpainting follows, with the rest figured out on the canvas.

Letting the specifics of a painting happen while applying the brush allows for “intuition and serendipitous little unanticipated moments” to play a greater role, the painter explained. “That’s why we work at an easel, right?” Meyer asked, then answered his own question: “to work and respond to what’s in front of us, then to step back, scratch our chins and think about what the work needs, as opposed to our initial conception of how we want it to turn out.”

Son of a Painter

Born in 1975 in Weymouth, Massachusetts, Meyer didn’t stay there long. His parents, back-to-landers, started a seasonal business and ended up dividing their time between an A-frame they built in Corea, Maine, and a houseboat in Florida.

While his father, Louis Meyer, a painter, tried to give his two sons instruction at an earlier age, they weren’t quite ready—or “didn’t yet feel the need to prove ourselves.” Meyer caught the bug in the large high school he attended in Florida, where the art room was an “oasis.” He recalled showing his sketchbooks full of copies of Conan the Barbarian comic strips and George Bridgman anatomy studies to the “most unattainable” girl in the school, who brushed him off but not unkindly.

Meyer counts himself lucky to have had many valuable teachers in his life, starting with his father, who gave early instruction to him and his brother Matthew “and was always there with a hilarious (and perfectly apt) burn.” The rambunctious way his family engages in painting surprises some people, but, he noted, “it definitely keeps it lively.”

Meyer attended Boston University as an undergraduate and earned his MFA at Lesley University. Richard Raiselis at B.U. and Tony Apesos at Leslie strongly influenced his development as a painter. Their “encyclopedic” knowledge of painting technique and the history of art proved invaluable to understanding the technical and conceptual sides of painting, he said.

That said, Meyer worried about his artistic future, exacerbated by the loans he and his parents took out to pay for school. He remembered a professor at the time saying, “There are 20 of you in this class—maybe five of you will still be making work five years out of art school.” Thankfully, Meyer had a built-in artistic community with his father and brother. “Every time they did an excellent painting,” he recalled, “I’d have to show them up with one of my own.”

Meyer maintains two studios, one at his family’s place in Corea, the other in Cumberland. The latter is in a shed that he insulated and drywalled; a wood stove keeps him warm in winter. He tries to do a painting session every day. Having taught drawing and painting for many years at Lewiston High School, he follows the schedule he had then: in the studio by 7:30 a.m. and wrap up around 3 p.m.

Contacted in July, Meyer was going full tilt on completing paintings for a show at Elizabeth Moss Galleries in Portland (November 7, 2025-January 17, 2026). The work is larger than what he usually paints. “It has been a lot of work,” he reported, “but I’m excited about how it’s turning out.” He finds there’s something very satisfying about painting large. “It just feels more natural to me.”

where there was a bed and breakfast called Sunset House on Jones Pond. Sunset House II, 2024, oil on canvas, 48 x 36 inches.

Meyer has been fortunate to have received several artist residencies over the years, including one on Monhegan Island in 2015. “It’s such a great resource for Maine artists,” he said; “I hope it lasts a hundred years.”

The residency took place in the summer when Monhegan is overflowing with visitors. Meyer soon realized he’d need to take special measures to avoid becoming a tourist attraction as he set up to paint plein air. “I like talking about my work,” he noted, “but once a critical mass of people is reached, not much painting gets done.” His solution? Wear huge 1970s-style headphones that can be seen from a distance and paint naked to the waist. “No one,” he asserted, “approaches the shirtless man.”

✮

Carl Little’s most recent books are the monograph John Moore: Portals and Blanket of the Night: Poems. He lives and writes on Mount Desert Island.

In addition to Moss Galleries, Meyer is represented by Page Gallery in Camden and One Center Gallery in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Visit nathaniel-meyer.com for more information.