All photos courtesy the artist except as noted

“No Mi’kmaq person I know, or Wabanaki person for that matter, does just one thing. We are busy, industrious people.”

So stated J. Rae Pictou in an interview last summer with The Bar Harbor Story, an online alternative community publication. As an artist, activist, storyteller, and business owner, Pictou, a Mi’kmaq tribal member, epitomizes this dynamic individual. Add martial artist to the list—plus a distinguished career in the museum world—and you begin to get the picture: She’s on the go.

Let’s start with beads. Pictou discovered beadwork at a summer camp for Indigenous kids on Sinclair Lake in northern Aroostook County when she was 8. Later, in the early aughts while working at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center in Connecticut, she and a fellow educator, Nevada Swan, would bead together. She also sat in on workshops with visiting instructors.

Pictou has returned to beads off and on throughout her life but has been more active in the past dozen years or so. The need to pay the bills has often gotten in the way, but, as she noted, when it becomes more about feeding her soul and less about “feeding the meter,” the work begins to blossom.

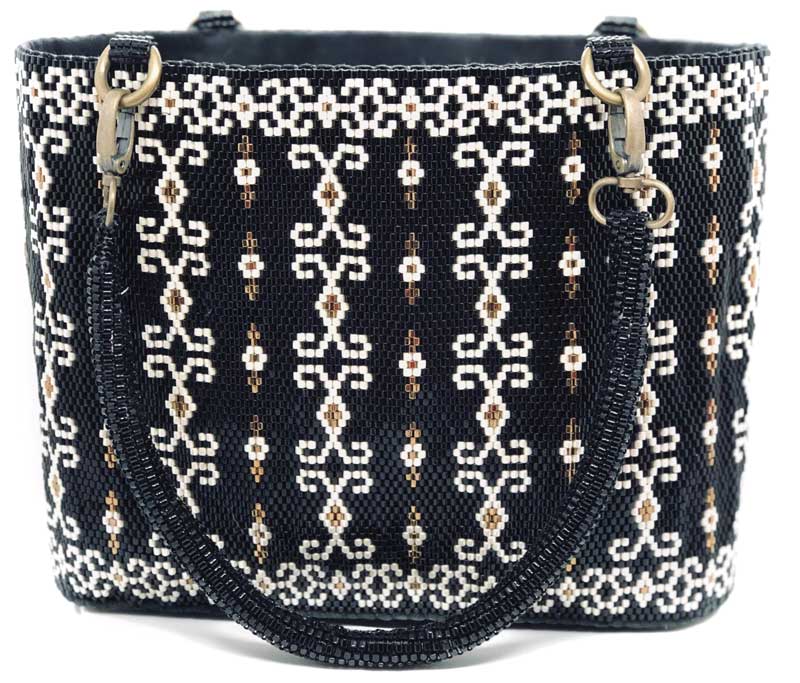

While she loves to learn the rules, Pictou also likes to test them. For a tote bag, she used large beads to create the structure. “It wasn’t beaded onto leather—the beads were the bag and then I sewed the leather onto them,” she explained.

Stained glass, Pictou noted, keeps her “in check.” During the pandemic, unable to practice martial arts, she needed a hobby that, she joked, “was just as dangerous” as karate. She chose stained glass where at any point in time, “there was the risk of cutting myself wide open.”

In the transition from beads to glass, Pictou began combining the two. One stained glass piece, Remember Who You Are, features a central beadwork square with a traditional double-curve Mi’kmaq motif. The four corners are Mi’kmaq petroglyphs from Nova Scotia where her family heritage begins.

Pictou also incorporated small mirror pieces, which let her catch a glimpse of herself, “in pieces, but never as a whole,” she writes, “because people tend to see Indigenous people that way and like to ask what percent Native blood we have.” The panel, which won the People’s Choice Award at the Abbe Museum’s Indian Market in 2021, hangs in her studio as a reminder “to keep pushing the boundaries.”

For inspiration, Pictou visits museum collections to study Indigenous designs, in particular those of Mi’kmaq artist-ancestors. She has been to Harvard’s Peabody Museum and the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor and looks forward to visiting the Museum of Natural History in Halifax, Nova Scotia, which boasts the largest Mi’kmaq quillwork collection in the world.

Pictou was the tribal historic preservation officer for the Aroostook Band of Mi’kmaqs for eight years. In that role, she spearheaded a revival of porcupine quillwork. With support from the National Park Service’s Tribal Historic Preservation grant program, she gathered a group of Mi’kmaq women to revitalize quill embroidery.

Calling themselves Quillers of the Dawn, in 2021 the group mounted Stitching Ourselves Together: Mi’kmaq Porcupine Quillwork at the Abbe Museum, with Pictou serving as the “citizen curator.” The museum drew on indigenous people’s knowledge and perspective as part of its mission to decolonialize the institution. “When we, as Mi’kmaq people, are involved in the curation and narration of our own history,” Pictou observed, “we are able to correct the incomplete and often erroneous narratives assigned to our existence.”

While serving as tribal historic preservation officer, Pictou and fellow tribal member Donna Sanipass created the Mi’kmaq Veterans Honor Wall in the tribe’s Cultural Community Education Center in Presque Isle. Among those honored are Pictou’s parents, Francis and Margaret Pictou.

At the time of the honor wall’s unveiling, Pictou said, “When we speak about our culture and heritage, we can never forget our veterans.” Near the top of the wall is the Mi’kmaq phrase Kepmite’manej: “Let us honor our soldiers.”

Bold Art, Strong Statements

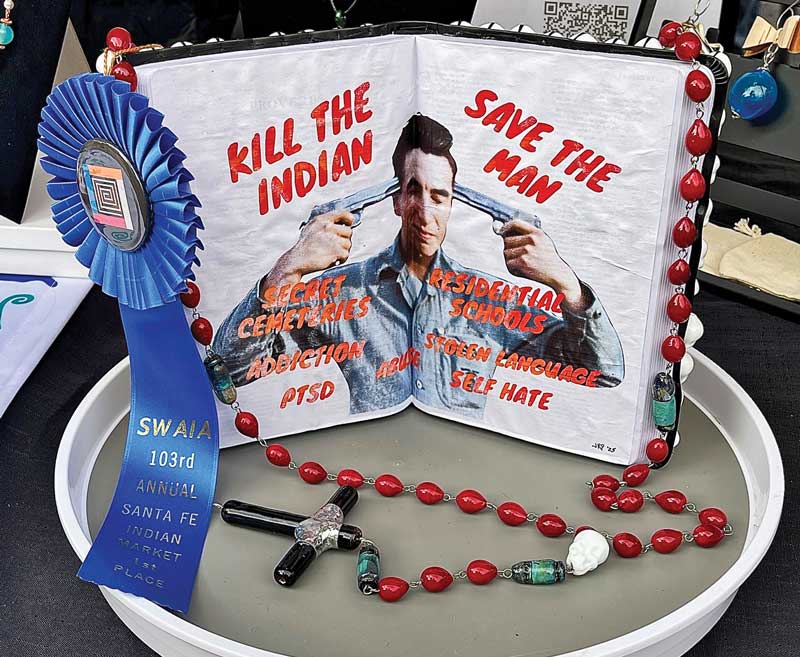

Pictou’s art often takes a confrontational turn. For the 103rd annual Santa Fe Indian Market last August, she showed Residential School Legacy: Blood, Bullets, and Lies, a mixed-media sculpture that represents her “Indigenous feminist rage” at what happened to her father—and, by extension, to her. Placed in the notorious Shubenacadie Indian Residential School in Nova Scotia, he experienced psychological and physical punishment at the hands of Bible-wielding staff and administrators, which led to life-long trauma. “They stole my father and my childhood,” she said.

The infamous motto of the residential schools, “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” accompanies a photograph of Pictou’s father taken when he was stationed with the Marines in Korea. In her statement for the Santa Fe show, she explained the significance of its various elements, from the beer bottle crucifix to the skull beads affixed to the front and back covers of a Bible. “I set out to ruffle feathers with this one,” she averred.

The piece took first place in sculpture at the Santa Fe fair, which featured work by 1,000-plus artists from more than 200 tribal nations. Pictou, who was attending her first market along with Kateri Aubin Dubois, a Maliseet bead artist, was stunned and pleased at this recognition.

Pictou’s rage against injustice also marks her contribution to Mawte: Bound Together, an exhibition in the Schupf Art Center, the Colby College Museum of Art’s downtown Waterville space (the show runs through April 13, 2026). Initiated and curated by Penobscot basketmaker Sarah Sockbeson, the show features 12 contemporary Wabanaki artists who employ Indigenized methodologies in their work.

Pictou’s piece, The Price of Existing, is a traditional Mi’kmaq headdress made from glass and stone that rests on a pool of blood-red glass flecked with gold-colored coins. “It is a statement of unceded Mi’kmaq territory in a modern world and the price we had (and have) to pay for survival,” writes the artist, adding, “We are still bleeding, still being treated as non-human, and yet still surviving at a terrible cost.”

Pictou began life in Patchogue, New York, on the south shore of Long Island. Her mother’s family was from the area. She was only a few months old when her parents relocated to Maine, to Mars Hill in Aroostook County. For her father, who was from Nova Scotia, it was like coming home.

Pictou earned a BFA at the University of Maine at Presque Isle. While she took fine arts classes—she loved the studio work—she best remembers Rena Ferneyhough, her art history professor. Ferneyhough taught her how to ask questions when studying an artwork, a lesson she has applied to her own work, as artist and as storyteller.

When she wasn’t pursuing art studies, Pictou focused on martial arts, taking karate instruction off campus. She has been a martial artist for over 30 years.

After graduating, Pictou decided to pursue another bachelor’s degree, this time in anthropology at the University of Southern Maine in Gorham. She had watched a television show on ancient tilework and felt a need to know more about it.

Ever the student, Pictou enrolled in a master’s degree program in American and New England Studies at USM in Portland. In 2001, she became museum educator for the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center in Connecticut. She later joined the staff at the Mystic Seaport Museum as education programs supervisor.

Returning to Maine in 2011, Pictou took a turn as executive director at the Bangor Museum and History Center before becoming curator of education at the Abbe Museum in 2014. Now a board member, she continues to champion this museum devoted to understanding the culture of Maine’s Indigenous peoples. As she said in a recent interview, she is proud of what the Abbe is doing “in terms of continuous refinement of Wabanaki history and truth-telling.”

In 2014, Pictou founded Dawnland Tours in Bangor and began her immersion into storytelling, a love she traces back to that childhood camp in northern Aroostook. Named for the tribal homelands of the Wabanaki People, the company, she has noted, “filled in the voids of history and culture that museums often don’t have the ability to publicly present.”

Pictou later changed the name to Bar Harbor Ghost Tours. On walks around the seaside town, she and her life-partner, D. Michael Fleming, a voice-over artist, share supernatural stories drawn from New England lore and Wabanaki spirit tales. For the past seven years, USA Today has ranked them among the top 10 ghost tours in the country (it came in seventh in 2025).

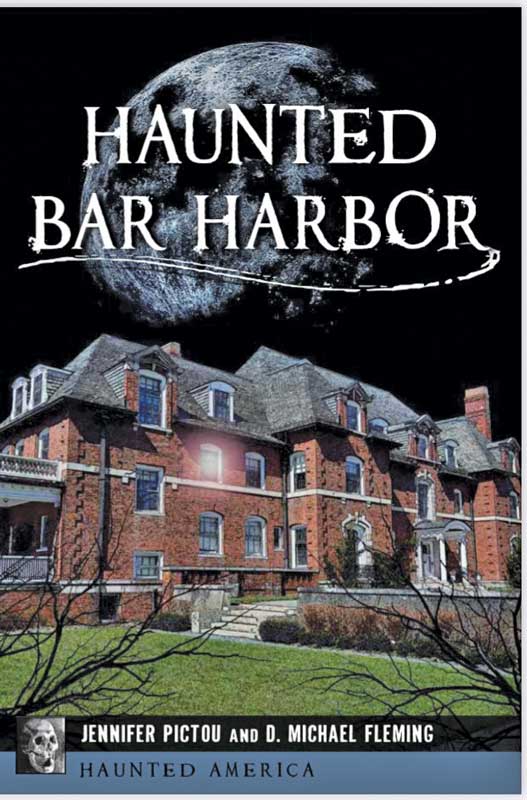

This past May, expanding on their “dark tourism” enterprise, Pictou and Fleming published Haunted Bar Harbor, part of Arcadia Publishing’s Haunted America series. Dedicated to “the spirits, without whom we would have no stories to tell,” the book features 11 tales with titles like “The Carpenter of Kennebec Street,” “Piano at the Brothel,” and “Criterion’s Veteran Ghost.”

In 2021, in the middle of the COVID pandemic, Pictou and Fleming moved to Freedom to help take care of his mother, Hilary Fleming, who was getting older and seemed to need more help. They became her regular caregivers when she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer; she passed in 2024.

The pair remained in what was Fleming’s childhood home. A 12-by-20-foot shed tucked among the trees serves as Pictou’s primary studio; she also has workspaces in the house. The shed studio provides a quiet and peaceful place where she can hear the crickets and the owls and witness the changing of the seasons. The space brings her back to the Mi’kmaq teachings of her Nova Scotian ancestors and the understanding that all life is connected.

✮

Carl Little is curating a show of Francis Hamabe (1917-2002) for the Castine Historical Society in summer 2026. Recent publications include a profile of poet Gary Lawless in the Island Journal and a study of the farm-to-table movement on Mount Desert Island in Chebacco, the journal of the MDI Historical Society.

See more of Pictou’s work at jraepictou.com. Visit museum.colby.edu for details about the exhibition “Mawte: Bound Together.”