Being a pilot without a plane, I don’t get to fly often. So, one October day in 2023, Certified Flight Instrument Instructor Chris Carroll and I had scheduled a date for a knock-the-rust-off dual flight around the Midcoast.

Knowing that I was a member of a local volunteer search and rescue group, he suggested checking out a wrecked boat he’d found off Louds Island in Muscongus Bay while flying a route for Penobscot Island Air from Vinalhaven to Portland. He said, we could “set up a mock search, as though we were looking for survivors aboard,” which sounded good to me. That day’s flight was fun and it was a useful exercise, but the boat we circled held no particular meaning for me. It was just some forsaken old wooden fishing vessel, I supposed, presumably damaged in a storm.

But then later that day, I met up with my daughter, Emily, at an event in Freeport, and I happened to mention the mock search flight over the wreck.

“Oh, that’s the boat uncle Ben worked on, isn’t it?” she asked. “I’ve been to that wreck. I have photos that David took from his kayak.”

Wait—what?

My daughter and her husband, David Mackeown, are Registered Maine Guides, and she teaches sea kayaking with L.L. Bean’s Outdoor Discovery Programs. The two have gunkholed all over the Midcoast in their kayaks. Earlier that day, as I flew over it, I’d had no idea the wreck off Louds Island had any connection to me.

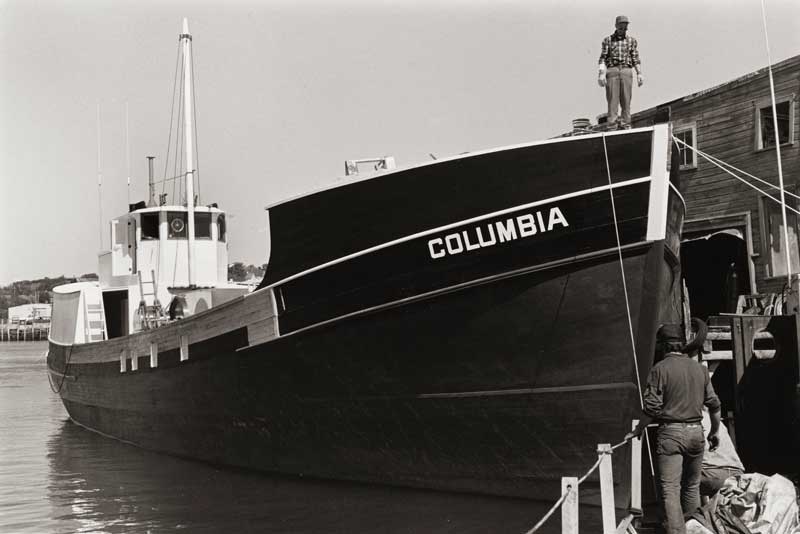

My brother, Ben, died in 2021. At his memorial gathering in 2022, somebody had a two-page centerfold spread from the Rockland Courier-Gazette dated May 9, 1985, about the launching of the scallop dragger Columbia that week at the Newbert & Wallace yard in Thomaston. The story introduced the men who had built her, my then 19-year-old brother included.

Emily and David then told me about discovering the wreck.

“We were planning this kayak trip in July, 2020, as something we could do together with some friends during Covid because it was all outdoors,” my daughter said. “We put in at Round Pond, spent the night camping on Thief Island, and we were paddling around and just stumbled across this thing. It was low tide, but you could still paddle up to the boat and all around it. The superstructure was kind of collapsing on one side. I took pictures of it to try and figure out more about it later. I did some research and found out the specs, and that it was considered a bit of a hazard now, and all of that, but the name didn’t mean anything to me.”

David mentioned how, “We just came upon it, like ‘Oh, hey, look at that!’ We had actually been at a beach just a little way around the island, for a picnic and swim, not knowing the wreck was nearby. We had no idea there was a family connection.”

Emily added, “I think I figured that out at Ben’s memorial. When I saw the newspaper clippings about the launching, I thought, “I’ve seen that boat!”

This triggered recollections of my brother as a teenager, talking about his boatyard jobs. Ben first worked at Erik Lie-Nielsen’s yard in Thomaston, beginning (I think) in 1981, before moving to the nearby Newbert & Wallace yard. He often spoke about the people he worked with, some of whom had skills that seemed right out of the history books. The specialized lexicon of wooden boats and hand-tool carpentry became my brother’s language, and his admiration for the skills of the older fellows was evident.

He talked about the older boatbuilders like Raymond Wallace, the yard’s owner, and Richard Dennison of South Thomaston, who clearly made an impression. They were his mentors. In later years, Ben became a finish carpenter, working on high-end construction, and he credited these men with teaching him to strive for quality as a carpenter, how to care for tools, and importantly, how to learn from those more experienced.

Connecting my short flight over the wreck with my daughter’s kayak trip and then finding out that my brother worked on construction of the boat would have been coincidence enough, but it seemed that the Columbia was still hankering for my attention.

Early in 2024 I was picking up something at E.L. Spear Lumber and Hardware in Rockland when Charlie Bagnall, across the contractor’s desk, told me that he thought he used to work with my brother. Sure enough, it turned out Bagnall was another of the guys from the boatyard who was mentioned in the 1985 Courier-Gazette story about the Columbia. Later that year, in December, Bagnall shared some boatyard memories with me.

“When I started (at the yard) the Columbia’s keel was laid, and about six or eight of the ribs had been put up,” Bagnall recalled. “There was no upper decking or anything else, so I worked on the Columbia almost from the beginning. I was about 24 or 25 years old and had just gotten married.”

I asked whether he was an experienced carpenter or boatbuilder before that. “Not at all,” he said. “The older guys, if they liked you, they took you under their wing and they taught you everything. Raymond Wallace—he owned the boatyard, Bentley Watts, Richard Dennison…”

I mentioned how my brother used to walk a mile or so many mornings to catch a ride to work with Dennison. Bagnall recalled that the craftsman had a farm to take care of in addition to his full-time job in the boatyard. “On top of working his eight hours of ‘bull work,’ Richard would go home and take care of the cows and everything else. These were tough old timers!”

“There were three or four of us young guys—Bentley Watts’s son Tim was there, too—and as the older guys saw that we were progressing, learning, they’d give us our own projects to work on,” Bagnall told me. “We started cutting out all of the planking. All of the lumber for those boats was cut at the sawmill that was right there. From what I remember, the truck brought those logs in, Raymond and the guys would run them through the sawmill that we had right there, we’d “stick” them, but for bending we didn’t need the lumber totally dried.

“Those planks were 2 inches thick, 18 or 20 feet long. We’d put them in a steam box for bending; there was a big wood boiler that was cooking all the time. Six or eight of us would carry one oak plank out and wedge it onto the side of the boat and bend it to shape. That oak was probably from Knox County. I know it was a local guy who used to come to the yard with his log truck.”

Bagnall said, “Ben and Tim and I got so we were able to do some things. They’d give us a pattern for a particular plank, we would cut it out and bevel the edges for the caulking that was done later on. I worked on the Columbia until we launched it, and then we were doing some final painting and tweaks.”

As Bagnall and I both had a history with hardware stores, I asked about specialty tools.

“An adze, for example—yes, that was hard to learn to use, you had to be pretty precise with it,” he said. “But that was one of those things that the old-timers had down in the yard. They taught us how to do that stuff. It was really fun.

“The tools that were used to caulk and put the cotton in the seams, those things get passed down now. I don’t know how else anybody would find that kind of tool.”

“I can remember heating pitch,” he added. “After they caulked the seams, they poured pitch and it would cool down in the seams, and then we’d chisel that off, smooth.”

“We were always using chisels that those older guys had. I remember one time Raymond bought some 12-inch by 2- or 3-inch-wide hand chisels, and he bought all of us young guys each one. It was a meaningful gift because we could show that we could use those tools.”

Bagnall continued, “The owner of the Columbia had two or three Newbert & Wallace wooden scallop draggers in New Bedford, and he was adamant that he wanted another wooden one, he didn’t want to go to the steel. He was having this one done, and it was out of the ordinary that a yard would still do it.”

“I think those old timers realized it was the last boat like that they were going to build,” Bagnall said.

Kevin Miller, in the Portland Press Herald in 2017, wrote that Columbia “was the last of a generation of wooden draggers that bridged the gap between the age of sail-powered fishing schooners and the rise of steel ships.”

If you look up the Columbia online now, you will find newspaper articles about various shipwrecks that are considered obstacles or potential hazards on the coast. A call to the Bristol Town Office to ask about the wreck’s current status or efforts to do something with this particular old boat confirmed a couple of things: First, Louds Island is not part of Bristol or any other municipality. Second, clearing a wreck is an expensive process, and plans are being made to remove the Columbia from the Louds Island shore, but nothing is likely to happen immediately. Nothing planned by humans, anyway; we’ll see what winter weather brings.

I am still hoping to fly over the Columbia again, and possibly kayak out to it with my daughter and son-in-law, this time remembering my brother, who had been one of Maine’s youngest old-school wooden boat builders.

I will ask my sister if she has seen a 12- by 3-inch chisel among Ben’s old tools, so I can bring it along next time I go to E.L. Spear’s and show Charlie Bagnall. It is indeed a small world.

✮

Eva Murray has contributed to Maine publications for 25 years. A year-round resident of Matinicus Island since her year-long stint as a one-room school teacher in 1987, she has promised her island neighbors she won’t write about them too much. Murray often seeks out freelance writing work that requires a hard hat.

The Columbia

According to an account from the Rockland Courier-Gazette in 1985: the Columbia was 88 feet long, had a 1,000-hp Caterpillar engine, a 6-foot propeller, and was built of an estimated 80,000 feet of oak. Construction took almost two years, beginning June 1983.