Any story about the bridge between Southport Island and Boothbay Harbor wouldn’t be complete without also telling the story about the Lewis family.

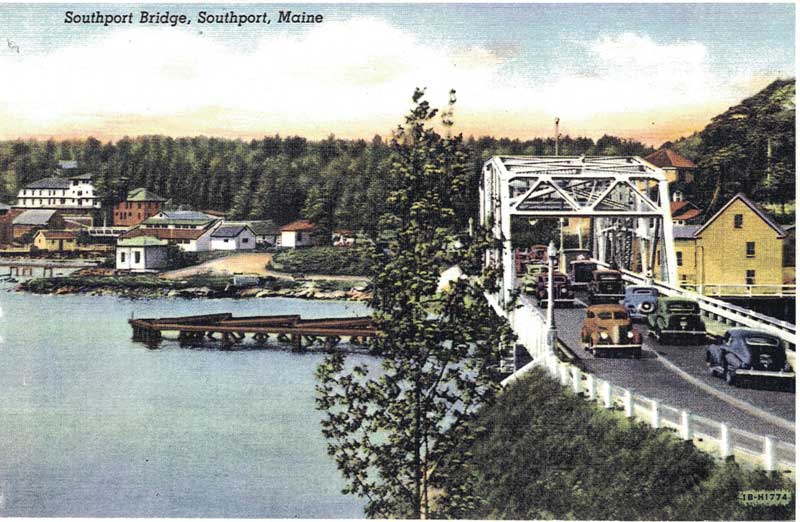

Townsend Gut is a narrow, deep passage separating Boothbay from Southport Island. The waterway has long been crucial to navigation between the Sheepscot River and Boothbay Harbor by shaving 10 miles off the long run around Southport Island and Cape Newagen. Spanning the fabled gut, the Southport Island Swing Bridge carries Route 27 road traffic to and from the island while allowing vessels to transit through.

The classic swing bridge was completed in 1939 and today sees as many as 3,000 bridge openings a month in the busy summer season. The span opens on the half hour when hailed by boaters on VHF marine radio channel 09.

For 85 years, across several generations, it was the Lewis family that was responsible for the daily operation of the Southport Island Bridge. The patriarch of the Lewis family, Norman, along with his wife, Mildred, began working for the bridge in 1940 and dedicated 43 years managing its operations.

Twins Dwight and Duane Lewis followed in their parent’s footsteps, each working as bridge tenders for 43 and 45 years, respectively. Their sister, Ruthie, and older brother, Donald, also devoted five years of bridge service.

On a hot summer morning in 2025, Dwight and Duane reminisced about their family’s time on the Gut. Dwight started off the conversation. “I remember just before he passed, Dad looking at you, Duane, and looking at me and saying, ‘You guys just finished working 40 years—what the Hell do you two want to keep it up for?’ Well, there’s no getting around it; we didn’t have nothing else to do, so I ended up working 43 years, and Duane worked 45 years.”

Typically, the Lewis brothers would work 48-hour weeks, keeping the bridge staffed to handle traffic 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. “Duane, you just wouldn’t give up, no matter what,” Dwight said to his brother. “You thought you had to be there for the people. Dad enjoyed it and Duane enjoyed it,” Dwight explained. But with 43 years under his belt, Dwight was ready to get done. “Myself, I couldn’t care less whether someone went through that bridge or not,” Dwight said. “I wanted to retire. But I loved it—I loved what I did, no getting around it.”

Norman Lewis passed in 2001, and the Lewis Family went on to dedicate a total of 147 years of continuous service to the Southport Island community and its beloved bridge. “Oh my God,” Dwight exclaimed, “our Dad was a very good man, but the age got to him. There’s no getting around it; he was a very bad diabetic, but he lived a good life, and he worked hard for 43 years,” he added.

Dwight recalls that his mother, as bookkeeper for bridge operations, was a real stickler for details and record-keeping. “She insisted that the name of the vessel, the vessel’s owner and the time and date the boat went through the bridge were properly recorded. After years as bookkeeper, she finally said to me, ‘Dwight, I’m done. I’ve done the bookkeeping all my life, and now my time is up. Here are the books—now you’ve gotta start doing it until you retire’—which I did, recording every vessel name, owner’s name and time and date of passage, until I retired.”

The Lewis family lived rent-free for years in a tiny state-owned frame house at the foot of the bridge on the Southport side. The old house had neither running water nor a septic system for the family of six. In the 1960s, the State declared the house uninhabitable and had it torn down. “We lived in that small house for years,” Dwight marveled. “That’s where we all grew up, in and around the water. My father and mother brought up six of us kids, five boys and one girl. And believe me, the girl got everything.

“I remember asking my father one time, ‘Why are you giving my sister money when I ask you for $5 and you won’t give me $5? ‘Because,’ he says, ‘you boys can go out and work and make $5. Now get the Hell out of the house and go to work!’

“But anyway, it was not easy living in this house because we did not have running water at all. We had to walk up a hill to my neighbor’s, go into her well and get our water. And that would be our drinking water, our cooking water, and everything. We had an outhouse for plumbing. And that wasn’t too good. The women could bathe in the bathtub if they wanted. That was up to them. But the boys always had to go to the Y, or go somewhere else to get our showers.”

According to Dwight, Duane had a reputation for crazy antics. “As a young kid, Duane had a tricycle. One day, he rode right over the bank and into the water, tricycle and all. He came out of the water all right, but no bike!”

“And then there was that hot day,” Dwight said to Duane, “and you looked at me and said, ‘I’m going to jump off the bridge’ and I said, you’re crazy. Next thing I knew, Duane, he had jumped right off the damn bridge and had to swim to shore. Duane always did the craziest things when he was younger; he did a lot crazier things than I ever did!”

The brothers love telling the stories that make up the Southport Bridge lore. “A car once drove off the bridge while it was open for a boat to pass,” Dwight chuckled. On June 21,1989, a Ford Escort, driven by 19-year-old Boothbay Harbor resident, Shani Orne, didn’t stop for the open bridge when the car’s brakes failed. Orne was able to steer around a car in front of her, before crashing through the signal gates sending the car off the bridge approach and into the chilly waters of Townsend Gut. “Yup, that car went right off the bridge and right into the water. And when Shani Orne’s car went overboard, why she went with the car! Well, she swam out of that car and was able to make her way to pilings underneath the bridge. My brothers Duane and Donald, and myself, went underneath and helped get her back on the bridge. She lived, but it was quite unbelievable that she survived!”

“Over the years, we had a very good time with the people,” Dwight recalled. “There’s no getting around it. Everybody liked us, and we liked them. Sometimes, well sometimes it didn’t work out that way. Sometimes, people would get frustrated and try to take it out on us.”

“I can remember one time, Duane, you had a sailboat coming up, and the lady on the sailboat was giving you holy Hell,” Dwight said.

“Yeah, we had a call that an ambulance was on the way to Southport on an emergency run,” Duane recalled. “About the same time, I received a VHF radio call from that woman on a 42-foot sailboat demanding a bridge opening so she could clear through. I said ‘no, we have an ambulance coming from Southport and I cannot open the bridge until he comes off!’ Well, this lady, she kept arguing and screaming right at me and I just kept saying nope, I’m just gonna make you wait.

“Finally, the ambulance crossed, and I opened the bridge,” Duane recalled. “Well, passing through, the woman looked up at me and she yelled, ‘I’m going to have you fired!’”

Sure enough, the woman complained to Duane’s boss. “So, my boss comes down with the Coast Guard, and they said ‘Duane, what happened?’

“I said, we had an ambulance coming and I made the sailboat wait and I’m proud of what I did.

“Well, the Coast Guard chief says to my boss, ‘Duane did the right thing, and I think we should fine the lady in the sailboat. And my boss says, ‘well, if the Coast Guard is going to fine her, then the State of Maine should fine her, too.’ So, they called her with news of her fines. Well, she was some mad and swore she would never come back to Maine again.”

An ambulance has right-of-way over any vessel, according to Duane. “If they have an emergency, even if the gates have been closed, we would have to open them back up—a big job especially in the old days when they had to be opened by hand,” Duane explained.

The State eventually automated the gates, making things much easier. But even then, right-of-way could be a challenge. Dwight recalls the time he had a vessel radio ahead on the VHF that they had a medical emergency on board the vessel and required an immediate opening. At the same time, an ambulance was making an emergency run and needed to cross the bridge. “So, who has a right of way?” Dwight asked. “Well, we don’t know, even today. So, in this case, whoever got to the bridge first, whether the boat or the ambulance, had the right-of-way.”

The brothers can remember only twice through the years that a vessel and an ambulance had simultaneous emergencies; in each of those cases, the boats beat the ambulances to the bridge and therefore were let through.

In 1987, the bridge was finally automated, but only after years of lobbying by locals. In June, 1976, the Boothbay Register’s Mary Brewer wrote about the region’s frustration with the condition and operation of the Southport Island bridge. “Southport’s bridge is the second busiest bridge in Maine, with thousands of openings a year. When a boat signals that it wished to pass through, the bridge tender must walk to the Boothbay Harbor end of the bridge, turn on the signal light to warn approaching traffic, close the gate, walk to the Southport end of the bridge, about 200 feet away, and close the gate to traffic, then return to the center of the bridge, climb the 20 steps up to the control room, and open the bridge for the boat to pass through.” After the vessel had cleared the bridge, the process was reversed to close the bridge for automobile traffic.

The automation upgrades greatly simplified the bridge operation. Warning lights, traffic gates, and bridge deck rotation could all be controlled from the operator’s shack. Attendants no longer had to brave the elements to manually open the bridge.

It was so simple, a child could operate the bridge, Dwight reported. “I’ll never forget one day a 7-year-old kid came up the stairs and asked, ‘Can I operate the bridge?’ He was a relative of mine, so I let him. I’m standing there, and I said, hit that switch up there and turn it to the right and you’ll see the gates going down. Then I says, here, you turn this switch and see the bridge move. ‘Hey,’ the kid says, ‘I could do this job!’”

And then there was one July day when Dwight had the gates going down when a car drove around the gate, stopping in the middle center span of the bridge. “So, I just left her right there in the middle of the bridge as it rotated open and I let the boat go through. Finally, I opened the gates up, closed the bridge and let her go—she was some happy to get off that bridge!”

But in spite of the accidents and near-misses, the bridge under the brothers’ watchful eyes saw its share of exciting events, too. Take, for example, the time a couple was married on the bridge.

The happy couple were friends of Dwight’s. Before he could close the bridge for the wedding, Dwight had to get permission from his supervisor. “I had to be careful,” Dwight recalls. “I didn’t dare do anything without permission in case my supervisor didn’t agree. After I gave my supervisor the details, he said “Don’t tell me about it. Just do it and get it over with.”

So, on October 26, 1989, at 1 p.m., Dwight lowered the gates, stopping traffic in both directions and a small entourage gathered in the center of the bridge to witness the marriage of Christopher Colpin and Caroline Streeble. According to Dwight, everyone in Southport knew about the wedding, and the drivers waiting on both sides were honking their horns in celebration!

The largest boat to ever go through the Southport Bridge was the 128-foot, three-masted Chesapeake ram schooner, Victory Chimes. Built in 1900, the Victory Chimes carried a beam of 23 feet, 8 inches, and a draft of 8-foot-6-inches. Engineless, a wooden yawl-boat with a 135-hp Ford diesel was used as a push-boat to maneuver the ship in close quarters.

“The Victory Chimes, she only came through once,” Dwight recalled. “Getting through that channel was something; she had very little space on either side, so it had to be a very calm day. All I can say is thank God it wasn’t windy! I remember a lot of people came down to both ends of the bridge to watch that big Victory Chimes go through and up the Gut. I remember telling my boss about it and he couldn’t believe it. They got through the bridge with the tender pushing the schooner with just inches to spare. Wow! That was unbelievable, no doubt about it!”

And then there was the biggest boat that never got through the Southport Bridge. “I remember years ago looking up to the North and there was a destroyer” Duane recalled. “The destroyer wanted to come down the Gut, but he had to turn and go around the island and then back up the river. It was a big ship and that ship was drawing too much water to pass!”

Weather has always played a role in bridge operations, often leaving the Lewis brothers to use their judgement, balancing the need to keep land traffic flowing to and from the island, the safety of passing vessels, and the well-being of the bridge and its mechanical systems.

Duane recalls one instance when the wind was gusting through the Gut at 80 to 85 mph. A vessel requested an opening. “Wow, I got the bridge open alright,” Duane recalls. But getting it closed was another matter. Duane called the Coast Guard in Boothbay Harbor. They sent two Coast Guard boats over and helped close the bridge and hold it in position so Duane could lock it down. “I called my boss up and told him what I’d done, that I’d taken a chance of opening the bridge in those winds. And he said, ‘Duane, you did a good job, but if you’d lost the bridge, you would be fired! But since you done a good job, you still have a job on the bridge.”

While the bridge was under regular assault by the weather, sometimes, the bridge saw abuse by boats. On August 18, 1989, Duane was on night bridge duty. Capt. David Winslow, at the helm of a Winslow tugboat, smashed against the heavy wooden fender system beams on the northeast side of the bridge. Daune was in the bridge operator’s office when a mighty crash sent him hurrying out to survey the damage in the darkness. “I remember I yelled ‘stop!’ to Capt. Winslow. And Winslow, from his tug, just yelled back ‘I don’t have time to stop, send me the bill!’”

“I called the Coast Guard and told them about it, but they didn’t do a thing, just let him go which I was surprised about. But David was a very good man,” Duane explained. On several occasions, the bridge mechanism failed, and the operators couldn’t close the bridge. “When it broke down, I couldn’t close the bridge. David had the tugboat, and he would pull the bridge closed for me—no kidding—and I never forgot that! I could always call him, ‘David, I need your help now’ and he’d come over and pull the bridge closed.” But we had a good time, so there’s no getting around it and he always helped me if I ever had a problem. The Coast Guard did it quite a few times, as well.”

Duane Lewis retired in 2013 after 45 years as a bridge tender. Dwight Lewis retired in 2012 after 43 years with the Southport Bridge. But they’re still sort of on the job. Today, the Bridge Brothers often give informal talks in Boothbay Harbor, regaling attendees with tales of the famous bridge and the family who dedicated their lives to it.

✮

Ted Hugger is a freelance writer living in Damariscotta. He cruises out of Southport Island with his wife and a very spirited Cardigan Welsh Corgi aboard their Grand Banks 42.