Barnacles like to be with other barnacles, and will fill every available space in the upper intertidal zone. Photo by Catherine Schmitt

Barnacles like to be with other barnacles, and will fill every available space in the upper intertidal zone. Photo by Catherine Schmitt

In the fall of 2021, bird-watchers across Maine rushed to see a rare bird, a barnacle goose that had fallen in with a skein of Canada geese. The vagrant goose had wandered from the rest of its kind, who nest above the Arctic circle and winter along the shores of Europe.

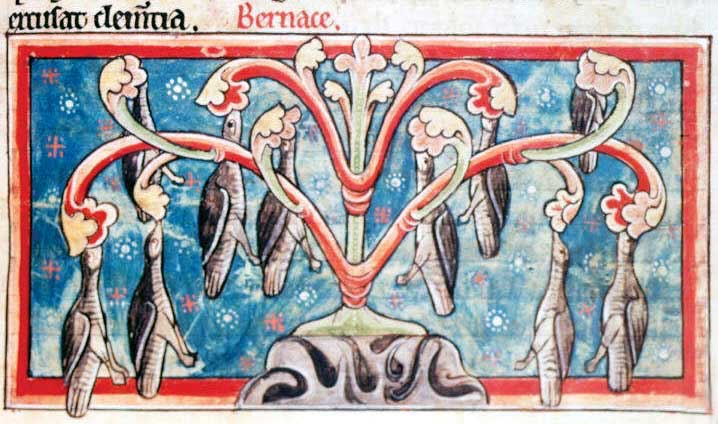

Illustration of a barnacle goose “tree” from a Medieval Bestiary in the British Library.Barnacle geese (Branta leucopsis) are known to be noisy and sociable, and usually stay together as a family through the winter. This one was alone. With its black collar and short white face, it stood out from the more gray and longer-necked Canada geese, who did not seem to mind the visitor. The geese spent a few weeks between the fields at Rockland’s South Elementary School and a particularly grassy neighborhood in Owls Head.

Illustration of a barnacle goose “tree” from a Medieval Bestiary in the British Library.Barnacle geese (Branta leucopsis) are known to be noisy and sociable, and usually stay together as a family through the winter. This one was alone. With its black collar and short white face, it stood out from the more gray and longer-necked Canada geese, who did not seem to mind the visitor. The geese spent a few weeks between the fields at Rockland’s South Elementary School and a particularly grassy neighborhood in Owls Head.

This goose had flown into Rockland, but back in the 16th century before anyone understood bird migration, it was believed that barnacle geese emerged from a crustacean called a goose barnacle, whose long neck and beak resembles a bird’s. Many a folk tale and medieval bestiary described and illustrated a paradoxical animal that was both bird and fish. What else would explain the sudden appearance of the avian geese on the water each fall? Or the beaked neck of a goose barnacle hanging from a piece of driftwood? This was a time when anything was considered to be fact once it was written down, and the association of goose and barnacle persisted for centuries.

In November 2021 in Rockland, Maine, no one who sought out the stray barnacle goose was rushing to find any other type of barnacles. But there they were, just below the yards where the geese fed, spattered across the rocks like stars.

At high tide, barnacles extend their feathery feet to feed. Photo by Alison McKellar

At high tide, barnacles extend their feathery feet to feed. Photo by Alison McKellar

Part of the background

Goose barnacles, Lepas anatifera, are creatures of the open ocean, attaching themselves to floating driftwood, buoys, flotsam, even the backs of turtles. Occasionally they wash ashore in Maine, just one of a thousand barnacle species found throughout the global ocean.

“Barnacles rank among the most biologically diverse, commonly encountered and ecologically important marine crustaceans in the world,” an international group of scientists wrote in the Zoological Journal of the Linnaean Society, in an article on barnacle evolution published around the same time the barnacle goose was becoming a minor celebrity in Rockland.

A common barnacle here in Maine is the acorn or rock barnacle, Semibalanus balanoides, which lives in the intertidal zone on rocks and other hard surfaces like pilings and ship hulls. Barnacles are not generally solitary; they live in clumps and clusters—like a gaggle of geese.

Strong-shelled and firmly cemented in place, barnacles shrug off even the strongest waves at high tide. Sharp-edged and closely clustered, they are a reminder that the sea is rough and therefore they tend to be avoided. Their ubiquity means they also tend to be ignored—except by naturalists.

Barnacles grow taller on crowded surfaces. Photo by Catherine Schmitt

Barnacles grow taller on crowded surfaces. Photo by Catherine Schmitt

One species does change into another

Before he wrote On the Origin of Species (but not before he had the idea for it), Charles Darwin nearly exhausted himself studying barnacles, which were at that time “imperfectly known,” a zoological riddle. He spent eight years at the microscope, analyzing fresh and fossilized specimens shipped to him from all over the world, publishing his results (“everything you ever wanted to know about barnacles but were afraid to ask”) in four thick volumes. Their diversity overwhelmed him—it was truly the “Age of Barnacles”—but it also motivated him.

As chronicled in Rebecca Stott’s book, Darwin and the Barnacle, Darwin used those barnacle studies to demonstrate his naturalist credibility, develop a network of supportive peers, and gather evidence for his idea explaining the incredible variation within and among species: that similar plants and animals did not appear on the Earth as-is, but transmuted—evolved—from a common ancestor.

With the latest and most powerful microscope available, Darwin could see that some barnacles were hermaphrodites, with both male and female parts, but since they couldn’t breed with themselves, they developed the longest penis, relative to body size, in the animal world. Other barnacles were mostly female, with males or male parts embedded inside of them.

By this time, people had concluded that barnacles did not grow on trees and hatch into geese. But barnacles did molt, Darwin found, which made them not mollusks as previously categorized, but crustaceans with multiple and diverse larval forms.

Unlike other crustaceans, however, in their final larval stage barnacles abandon their free-living youth for a sessile adulthood.

Constellations of barnacles on rocks help to illustrate the height of regular high tides. Photo by Catherine Schmitt

Constellations of barnacles on rocks help to illustrate the height of regular high tides. Photo by Catherine Schmitt

How to choose a home

After several months growing and swimming around the sea, the acorn barnacle selects a place to settle down.

Smaller than a millimeter, with compound eyes but no mouth, the late larval barnacle is highly specialized for sensing color, texture, water speed and temperature, and chemical signals. It wants to avoid predators and the turbulence of rockweed, but find abundant planktonic food sources. It wants to be with other barnacles, and seeks out patches of white amid the blue, green, and brown of shallow coastal waters.

With a pair of dextrous antennules, the barnacle “walks” around and explores potential home sites. Finding one, it releases a lipid-rich matrix to clear the area of any filmy bacteria or algae, and then begins to cement itself, head-down, to its chosen surface. The barnacle extracts minerals from the surrounding seawater to build its six-walled shell.

And there it stays.

Their persistent habit has led to “barnacle” becoming synonymous with people and things that are annoying, clingy, uselessly impeding. But their permanence is also a natural wonder.

The adhesive produced by barnacles stays stuck in both wet and dry conditions on all types of surfaces, accommodates the expanding girth of the animal growing above it, and resists scraping and pulling by claw, foot, and tooth. This strong adhesive is made of hundreds of proteins. Many are unique and some are involved with immunity and wound healing, similar to blood-clotting proteins in humans. Scientists at Massachusetts Institute of Technology recently developed a medical paste inspired by barnacle glue that can instantly stop severe bleeding.

In the clarity of waves

Its special cement helps the barnacle live the rest of its days, months, or even years inside its protective shell, which it opens only to reproduce, and to eat. Through a diamond-shaped opening, the barnacle extends its feathery feet, called cirri, into the current and captures algae and other particles. Sometimes, if there is no current, they can stir their feet to draw food towards them. In this way, barnacles help to keep coastal waters clean.

“Where the tides rise and fall over a wide expanse of intertidal rock,” wrote Rachel Carson of Maine’s seaweed-covered shore in The Edge of the Sea in 1955, “the barnacles stand out with sharp distinctness, and in the clear water that pours through the forest like liquid glass, their cirri flicker in and out—extending, grasping, withdrawing, taking from the inpouring tides those minute atoms of life that our eyes cannot see.”

The reference to glass and light echoes Marianne Moore in her 1918 poem, “The Fish,” inspired by a summer visit to Monhegan Island:

The barnacles which encrust the side

of the wave, cannot hide

there for the submerged shafts of the

sun,

split like spun

glass, move themselves with

spotlight swiftness

into the crevices—

in and out, illuminating

the

turquoise sea

of bodies.

There must be billions of barnacles encrusting the coast of Maine—billions of individual animals that have made a choice to be where they are. “Choice” may be too strong of a word. But barnacle settlement is deliberate.

How much of a choice did the barnacle goose make to join birds of a different feather on the opposite side of the ocean?

The goose’s white sides made it stand out, like the white crust that marks the barnacle zone along the shore. What is made clear by the decisions of barnacles and geese is that home can be found among others of the same kind—and among the kindness of others.

Catherine Schmitt is the author of A Coastal Companion: A Year in the Gulf of Maine from Cape Cod to Canada.