Photos By Jerry Monkman

What characterizes the North Woods? It is rough, utilitarian, desolate, and vast. It is a place of powerful rivers that drain its lands—the Penobscot, Kennebec, Androscoggin, Allagash, St. John, Machias, and St. Croix. It is a place of mountains shaped by the glaciers of the past that emerge from the spruce and fir forests with granitic splendor. It is a place where you can feel wildness in the moss underfoot and in the lynx, moose, pine marten, and other animals that live here. There are thriving wild native brook trout—the healthiest populations in the eastern United States. Much of the North Woods has been designated as globally significant for migratory songbirds. It has inspired magnificent art, writings, and scientific discovery. In my humble view, the untamed qualities of Maine’s North Woods are a match for other regions in the western United States and Alaska.

One has to be intrepid when exploring the North Woods. There are few directional signs, and trailheads are often not well marked. A traveler needs to be brave and prepared on the interlaced network of dirt roads that extend for miles and miles, roads renowned for shale bits that puncture the strongest of tires. Extremely important is knowing how to read maps and follow a compass, for one can get lost easily—even in this age of GPS. Being self-sufficient is essential. The North Woods is not manicured or neat. The place is rough, chaotic, and not easily enjoyed. And there are insects—blackflies in the spring, mosquitoes in early summer, and later, the horse flies. It is not pretty in a quaint, tidy manner.

The Roach River headawaters will make their way to the sea. Photo by Karin Tilberg

The Roach River headawaters will make their way to the sea. Photo by Karin Tilberg

Still, is there a landscape within the heart that emerges when you know you have found home? I had a “home” I was unaware of until I first experienced it—Maine’s North Woods. I am not alone in loving the North Woods; its power, mystique, and undeveloped bigness enrich the soul for many individuals. I write because of historic conservation measures that have unfolded in this place that I love.

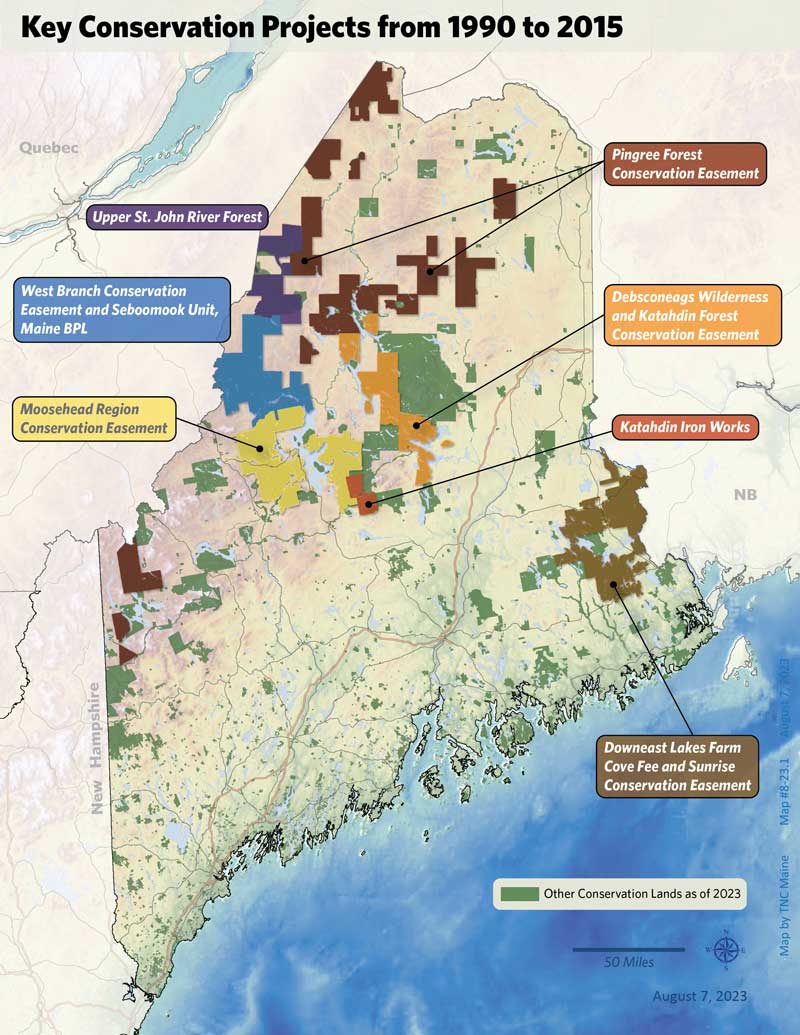

The magnitude of conservation in Maine’s North Woods from 1990 to 2015 resulted from a massive shift in land ownership from primarily paper companies to a diverse array of landowners. Conservation achievements in this era included players from major state, regional, and national conservation groups such as The Nature Conservancy, the New England Forestry Foundation, Trust for Public Land, the Forest Society of Maine, The Conservation Fund, and many others along with Maine state agencies and elected officials. Challenges and achievements captured imaginations. The willingness of forest landowners to work with conservation partners in pursuing conservation easements and acquisitions was essential. Thousands of individuals engaged in debates, funding, and conservation outcomes.

Other significant conservation in the North Woods has taken place since 2015, but the opportunities that led to these were second or third generation from the big paper company sales and family estate planning initiatives characterizing the late 1980s through the early 2000s.

Stunning lakes, mountains and forests create a vast landscape.

Stunning lakes, mountains and forests create a vast landscape.

Maine’s Great North Woods—12 million or so acres, three and a half times the size of Connecticut—reverberates as a vital part of American history. The North Woods is the home of the Wabanaki. Their ancestors were the first people to inhabit this region, doing so for 12,000 years. It forms the backdrop for European settlers who made their home here, for breathtaking logging lore, for an era of papermaking, and for famed outdoor recreation adventurers and feats. This hauntingly beautiful yet roughly powerful place has inspired legends from antiquity and artists and writers of all genres.

The North Woods contains a rich diversity of ecosystems, from alpine tundra and boreal forests to ribbed fens and floodplain hardwood forests. It is home to rare plants and animals. It has been designated a globally Important Bird Area, or IBA, by the National Audubon Society. It is the last stronghold for wild brook trout in the eastern United States. Unfragmented forests and diverse topography make it a highly resilient landscape in the face of climate change. The forests sequester and store carbon equivalent to approximately 91 percent of greenhouse gases emitted every year in Maine.

The inland waterways are a vital connector of forests to the marine world. Fish, wildlife, trees, and plants have evolved in an interconnected circulatory system of forests, rivers, and ocean environments. Atlantic salmon symbolize healthy, connected ocean and freshwater systems as they live and move between both; indeed, salmon are creatures of the forest.

The Nature Conservancy, Maine ChapterIn the late 1980s, approximately 5 percent of Maine’s statewide total of just over 20 million acres was either in public ownership or conserved in a permanent manner. (For this discussion, the term conservation refers to public ownership, ownership by non-governmental organizations with a conservation mission and in a permanent status, or with permanent conservation easements on the land.) In less than three decades, the amount of conservation lands rose to 21 percent of Maine, amounting to 4 million acres. Embedded in this dramatic increase lie stories of people who care about Maine’s forests, who depend on woodlands for livelihoods, and who demonstrated incredible generosity. There were residents in the few communities near the big woods, guides depending on the woods, mill workers and truckers not only depending on the forests for livelihood but hunting, fishing, and relaxing. There were members of Wabanaki nations who supported measures to sustain rivers and forests that have been their home since antiquity. There were conservation organizations, boards of directors, and individuals who took significant financial risks. And there were forest landowners willing to consider unusual conservation strategies, often waiting years to close on projects.

The Nature Conservancy, Maine ChapterIn the late 1980s, approximately 5 percent of Maine’s statewide total of just over 20 million acres was either in public ownership or conserved in a permanent manner. (For this discussion, the term conservation refers to public ownership, ownership by non-governmental organizations with a conservation mission and in a permanent status, or with permanent conservation easements on the land.) In less than three decades, the amount of conservation lands rose to 21 percent of Maine, amounting to 4 million acres. Embedded in this dramatic increase lie stories of people who care about Maine’s forests, who depend on woodlands for livelihoods, and who demonstrated incredible generosity. There were residents in the few communities near the big woods, guides depending on the woods, mill workers and truckers not only depending on the forests for livelihood but hunting, fishing, and relaxing. There were members of Wabanaki nations who supported measures to sustain rivers and forests that have been their home since antiquity. There were conservation organizations, boards of directors, and individuals who took significant financial risks. And there were forest landowners willing to consider unusual conservation strategies, often waiting years to close on projects.

Until the 1980s, land holdings in the Maine woods did change ownership, but only occasionally, usually resulting from corporate mergers. A defining feature was mills owning forestland that supplied them. However, by 2015 all the paper mills had disposed of their timberlands.

The contiguous unfragmented forests today look much as they have for centuries.

The contiguous unfragmented forests today look much as they have for centuries.

Why this sell-off? Drivers included peaking of paper demand in North America, high energy prices and intensified global competition, belief that mills could obtain needed fiber on the market and through supply contracts, and emergence of institutional and other investors interested in owning managed timberland. Also, the 1986 Tax Reform Act removed beneficial capital gains treatment for paper company ownerships.

Many new owners were timber investment management organizations, or TIMOs. Investor funds were pooled to acquire large tracts of forestland. Typically, the TIMO would acquire forestland, manage it for a period of time (for example, 15 years) and then sell the property. Another new form of forest owner was a real estate investment trust, or REIT, which owns, and in most cases operates, income-producing real estate.

The new TIMO and REIT owners sent ripples of anxiety through rural communities. Would they divide and sell the land? Would they post no-trespassing signs and prohibit hunting and fishing? How would these new owners manage the landscape-scale forests of Maine?

The story of Great Northern Paper illustrates the bewildering, intense quality of these sales. Founded in 1898, GNP began manufacturing paper in 1900 and carved the mill town of Millinocket out of the woods. Strategically located on the West Branch of the Penobscot River, Millinocket enjoyed an abundant supply of wood for the log drives that brought wood to the mill, and available hydropower.

GNP assembled its 2.3 million acres by the late 1950s. In the late 1980s, the Maine lands supported two large paper mills and a large sawmill, employing upwards of 4,000 workers. In 1991 the Maine operations with the land were sold to Bowater, Inc. In 1998, Bowater began selling the landholdings in pieces. By 2005, GNP’s forest empire of 2.3 million acres had fragmented: about 60 percent was owned by financial investors; about 28 percent by forest-related entities; 50,000 to 60,000 acres were designated ecological reserves owned by conservation organizations; and 500,000 acres were conserved with working forest conservation easements. GNP’s massive ownership had split into at least 15 ownerships.

Essential to North Woods conservation have been conservation easements. A conservation easement is a voluntary, legally binding agreement between a landowner and a land trust, governmental agency, or other qualified entity, through which certain rights inherent in ownership of the property are permanently transferred. The essential purpose of conservation easements is to protect in perpetuity the natural, scenic, agricultural, recreational, forest, or open space values of the property or maintain or enhance a parcel’s air or water quality.

At 12 million acres, the North Woods is larger than three times the size of Connecticut.

At 12 million acres, the North Woods is larger than three times the size of Connecticut.

Conservation easements are relatively inexpensive compared to fee acquisitions of land, which stretch scarce conservation dollars. The cost of purchasing an easement on forestland in the North Woods is usually less than half that of acquiring the property outright, depending on rights transferred in the easement and the land’s amenities.

One example of many extraordinary conservation successes during this era was the courageous purchase by Downeast Lakes Land Trust of 27,080 acres and the neighboring purchase by the New England Forestry Foundation of a conservation easement on over 311,648 acres. The seller was a TIMO that had bought its land from Georgia Pacific. At the time, as Maine director for the Northern Forest Alliance, I traveled frequently to Grand Lake Stream, a small village in eastern Maine surrounded by expansive lakes and waterways. I met wonderful people in Grand Lake Stream. Some owned small businesses, many were Maine Guides making their livelihoods by bringing so-called “sports” to fish and hunt, and some had retired there. Then, and perhaps still, Grand Lake Stream hosted more Registered Maine Guides than anywhere else in the state.

In 1999, Georgia Pacific had sold 446,000 acres surrounding this region to a TIMO in a dramatic, unexpected sale. It shook the community deeply. What would happen to the miles of undeveloped lakeshore that formed the backbone of the guiding economy? Would development harm fisheries and scenic resources they depended on for their livelihoods? Would the new owner’s forest practices threaten wildlife habitat? Would traditional uses and public access for fishing and hunting be closed off? Would buyers liquidate the forest resource that many depended on for logging work?

Casting on a stream brings peace and connection deep in the forest.

Casting on a stream brings peace and connection deep in the forest.

Residents were motivated to act. Forming Friends of the Downeast Lakes, later evolving into the Downeast Lakes Land Trust, they enlisted as an experienced partner the New England Forestry Foundation (NEFF), which had led the effort that resulted in a conservation easement on over 700,000 acres of Pingree family lands in the North Woods. I recall sitting in a living room on the shores of West Grand Lake as this humble group considered protecting over 300,000 acres of forestland with extremely valuable shorelines. “How much is this going to cost?” Keith Ross of NEFF was asked. “Well, perhaps $30 million and perhaps millions more,” he replied. There was complete silence in the room.

Such sums were fantastical to this group. After a long silence, heads slowly begin to nod in assent as they turned to one another seeking affirmation. To a person they agreed, “OK, let’s go for it.” I have seen other acts of citizen courage, but this moment was unforgettable. The place meant so much, and fate had put at risk their home and well-being. They were going to fight for it.

Those working on the project worried over years that they would not come up with the funding and suffered true angst. Steve Keith, first executive director of the Downeast Lakes Land Trust and one of the heroes of this story, credited board and committee members’ passionate support of the project for its success. Multiple collaborating organizations helped, and the easement and land purchases were completed in 2005.

Such gritty perseverance and unwavering dedication of many individuals from all walks of life form the backdrop behind the efforts leading to multi-year, complex, exhausting, and profoundly inspirational initiatives to conserve land in the North Woods. Conservation was accomplished in a fashion that honors Maine traditions and benefits and is accepted by the great majority of Maine people. In most other parts of the country, major conservation achievements have only accrued after pitched public battles. Usually, Maine’s conservation achievements are the result of collaboration.

Numerous initiatives continue to conserve the forested landscape of Maine’s North Woods by committed landowners, individuals, governmental agencies, donors, and organizations that value its unique, increasingly rare attributes. Efforts expand to acknowledge this region as the Wabanaki homeland and find ways to support their enduring relationships with the woods and to return to them culturally significant land that was wrongly taken. Maine’s North Woods may well become even more important as resilient habitat for plants and animals, for carbon storage, for new wood fiber commodities and long-lived wood products, and as a place to find personal strength and renewal. Let’s not dally in continuing to bring conservation to the great North Woods of Maine.

✮

Karin Tilberg recently retired as president of the Forest Society of Maine following decades working on Maine conservation in the private and government sectors. She holds a Wildlife Biology degree from the University of Vermont and a law degree from the University of Maine School of Law. She lives in Salsbury Cove. This article was adapted from her book, Loving the North Woods: 25 Years of Historic Conservation in Maine, published by Down East Books.