Today, visitors get view of Flagstaff Lake from the Cathedral Pines Campground, with the Bigelows beyond. Photo by Mimi Bigelow Steadman

Today, visitors get view of Flagstaff Lake from the Cathedral Pines Campground, with the Bigelows beyond. Photo by Mimi Bigelow Steadman

With Kingfield and Carrabassett in the rearview mirror, we continued on Route 27 another 15 or so miles to the village of Stratton. Part of the town of Eustis, it lies in a valley in Maine’s northwestern mountains. Just beyond the commercial center, we pulled into a scenic turnout beside Flagstaff Lake—at more than 27 miles long, Maine’s fourth-largest lake. We’d come to learn the unsettling backstory of this expanse of water, which spreads out below the towering peaks of the Bigelow Mountain Range.

I’d heard bits of the heart-tugging tale years ago, and then again more recently when I joined a wintry snowshoe trek beside the lake to spend a night at Flagstaff Hut, part of the Maine Huts & Trails system. When the frozen lake lured us onto the ice, I was captivated by thoughts of what once happened beneath us.

This photo of Flagstaff’s Main Street, now in the Penobscot Marine Museum’s collection, appears on an information sign by the lake. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

This photo of Flagstaff’s Main Street, now in the Penobscot Marine Museum’s collection, appears on an information sign by the lake. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum Prior to being flooded, Flagstaff village was a waterside community. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Prior to being flooded, Flagstaff village was a waterside community. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

On our more recent visit, on a sunny day last October, we rendezvoused at the turnout with Master Maine Guide Jeff Hinman, who operates summertime nature and history pontoon-boat tours here. He’d brought along a map showing how differently the view in front of us had looked before 1950. That’s when Central Maine Power flooded the Dead River Valley to create Flagstaff Lake as a reservoir to hold spring runoff from the Upper Dead River watershed; the water is later drawn down to power hydro dams on the Kennebec River.

“Flagstaff village was here,” Hinman said, pointing to the old, hand-drawn map. “Dead River village was over here.” The hamlets of Bigelow and Carrying Place were also flooded. Residents were notified of the plan years in advance, though many thought it would never happen. Over the course of several decades, CMP bought up numerous houses and farms. Other owners moved their structures out of harm’s way. Some were still awaiting settlements from CMP when their homes were inundated.

“The roofs stuck up out of the water afterwards,” Hinman said. “The next winter when the lake froze, crews went out and burned them. When the water is low, you can still see old stone foundations below the surface.”

This street view of Flagstaff Village shows a well-kept neighborhood. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

This street view of Flagstaff Village shows a well-kept neighborhood. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

On a couple of informational signs beside the lake, I found an early 1900s photo of Flagstaff Village’s Main Street showing E. J. Leavitt’s General Store and Post Office before the flooding. There was also an “after” picture of the building standing in water up to its second story. Other photos captured Evelyn Leavitt assisting a customer in the general store, and a class of youngsters posing on the elementary-school steps. It was difficult to imagine how hard it was for all the families of the Dead River Valley to face the obliteration of their homes, their land, and their livelihoods, and to have to start over somewhere else.

The name Flagstaff hints at another historic event: In 1775, Colonel Benedict Arnold and 1,100 soldiers embarked on an arduous expedition up through the Maine wilderness in a failed attempt to capture British-held Quebec City. (This occurred several years before he became a traitor.) Legend has it that Arnold planted a flagstaff here before moving on, and the village’s name commemorates his gesture.

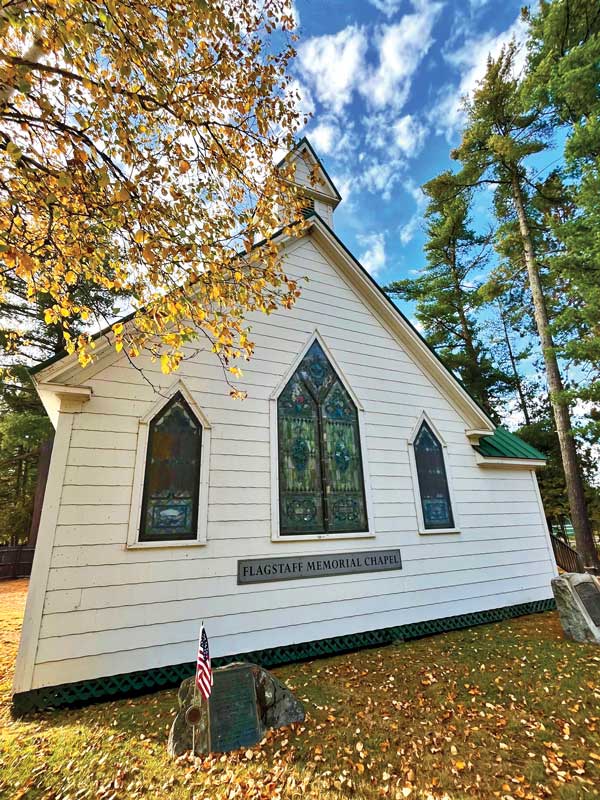

The Flagstaff Memorial Chapel was built from parts of a church that stood in Flagstaff Village before the flooding. Photo by Mimi Bigelow SteadmanThe Arnold Expedition visit also inspired the name of the Bigelow Range. According to a contemporaneous account, Major Timothy Bigelow summited one of the peaks in the long mountain ridge “for the purpose of observation.” He’d reportedly hoped to see the spires of Quebec City from the top. Obviously, his geographical knowledge was flawed.

The Flagstaff Memorial Chapel was built from parts of a church that stood in Flagstaff Village before the flooding. Photo by Mimi Bigelow SteadmanThe Arnold Expedition visit also inspired the name of the Bigelow Range. According to a contemporaneous account, Major Timothy Bigelow summited one of the peaks in the long mountain ridge “for the purpose of observation.” He’d reportedly hoped to see the spires of Quebec City from the top. Obviously, his geographical knowledge was flawed.

A much more serious miscalculation led to a fatal midair collision over the lake in 1959. During a radar training mission conducted by the U.S. Air Force’s 37th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron (out of Burlington, Vermont), one of the Convair F-102 Delta Dagger fighters accidentally struck the wing of a Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star that was posing as an enemy aircraft. Both planes crashed. The crew of the T-33 ejected successfully, though one man died when his parachute malfunctioned. The pilot of the F-102 was never found.

In the winter of 1979, a local man snowmobiling on the lake came upon part of the F-102 protruding from the ice. Hinman knew him and related the story to us: “He removed one of the bombs from under the wings, took it home, and set it on his kitchen table. When he called authorities to alert them of his discovery, they stressed that the bombs on the plane were still live. So when officials came to his house to be directed to the crash site, he hid the bomb in the trunk of his wife’s car! In the end, he did turn the bomb in.” The hazardous wreckage was safely destroyed by authorities.

After leaving Hinman, we drove a few miles farther to the Cathedral Pines Campground. Walking on its sandy beach beside Flagstaff Lake, we spied fresh moose hoofprints. We weren’t treated to a sighting of the animal, but it was exciting to think it could be in the piney woods nearby. As we took in a panorama of the lake and the Bigelow peaks just beyond, we watched a family paddle by in two kayaks. I wondered if they knew about the dramatic events that unfolded here.

Before leaving the area, we made one more stop on Route 27. The Flagstaff Memorial Chapel was built using the pulpit, pews, bell, and other parts from a church where Flagstaff villagers once worshipped. The simple, white structure, and the relocated graves beside it, are a poignant reminder of a sorrowful chapter in Maine’s history.

✮

Contributing editor Mimi Bigelow Steadman lives on the Damariscotta River in Edgecomb.

If you go to Flagstaff Lake

On the Water

For those trailering their own boats to Flagstaff Lake, a launching ramp can be found diagonally across Route 27 from the scenic turnout just north of the village of Stratton, and at Cathedral Pines Campground. The private marina at Flagstaff Landing has slips available both seasonally and nightly. Master Maine Guide Jeff Hinman cautions that the lake is shallow, and old tree stumps left from clearcutting done prior to the flooding can pose a hazard. Boaters who are unfamiliar with the lake should exercise caution.

Do

From late May through September, Jeff Hinman operates Flagstaff Scenic Boat Tours aboard his 22-foot pontoon boat. Two-and-a-half-hour trips highlight the area’s history and wildlife. Other tours include full-moon cruises and wildlife-photography outings. In a former church built in 1878 at the center of Stratton village, the Dead River Area Historical Society houses collections pertaining to native people, logging, guides and sportsmen, and the lost villages. It’s open on weekends in July and August.

Eat

Expect a warm welcome at the White Wolf Inn & Restaurant from owner Sandy Isgro, who bakes bread every morning. It stars in such sandwiches as grilled cheese and a turkey club with roasted-in-house turkey. Across the road, order from the large menu of comfort food at Backstrap Bar and Grill. There’s a meat market in the back room; the packaged game sausages (venison, duck, boar, and more) are excellent. Open for breakfast, brunch, and lunch, the Looney Moose Café serves such perennial favorites as chili in a bread bowl, meatloaf, and burgers. Get there early to score some of the freshly made donuts. One of 11 locations throughout Maine, Brickyard Hollow Brewing Company can be found in a renovated barn at Flagstaff Landing. The menu includes lots of popular pub food, plus the company’s own craft beers. Accommodations and a marina are also on site.

Paddle and Hike

Accessible year-round, the nonprofit Maine Huts & Trails system offers more than 50 miles of non-motorized, multiuse wilderness trails that lead to several off-grid eco lodges. The trails are free to the public; most are considered easy. Some are groomed for winter skiing. Bordering much of Flagstaff Lake, the Bigelow Preserve provides exceptional opportunities for backwoods hiking and climbing. Covering more than 36,000 acres of public land, it encompasses all seven summits of the Bigelow Mountain Range, including one of Maine’s 10 4,000-foot-plus peaks. A segment of the Appalachian Mountain Trail runs through the preserve. The 740-mile-long Northern Forest Canoe Trail passes across Flagstaff Lake. Kayaks and canoes may be rented at Cathedral Pines Campground. Lodgers staying at Flagstaff Landing have complimentary use of kayaks and canoes. Remember that this is a reservoir—check the dam release schedule in advance of your outing. Also bear in mind that winds can pick up quickly over this large expanse of water. Set on 300 acres, the town-owned Cathedral Pines Campground includes a sandy beach on Flagstaff Lake that is also open to daytime visitors at no cost. It also maintains 115 tent and trailer sites in a quiet, wooded setting.