The author develops his casting from a perch at the water’s edge. Photo by Karin Tilberg.

The author develops his casting from a perch at the water’s edge. Photo by Karin Tilberg.

I had no idea the sport of casting flies for fish would so sharpen my appreciation of Maine’s history, cultures, and the natural systems that can be found between the North Woods and the sea. This discovery came following widowerhood, when I decided that this old dog could—indeed must—learn new tricks, especially since it involved sharing the passion for flyfishing my coach and now wife, Karin Tilberg, enjoys.

The learning curve for me was—and still is—long, challenging, and a window on an extraordinary obsession. Still to come is mastering tying flies to the clear, unbelievably skinny monofilament leaders that one can hardly see. Sure, I’ve tied knots in ropes of all sizes, but the leader on a fly rod is something totally different. And the variety of flies! Which type and size to use on what waters for what fish, at what season, and in what weather? Just the names of the flies are mind-boggling and perhaps ludicrous: Maple Syrup, Grizzly Wulff, Montreal Whore.

The essence of the North Woods enchants as the sun sets over a remote pond in the western Maine mountains. Photo by Ben EmoryOn a drive north into Aroostook County, my wife directed without warning that we turn into a nondescript driveway in Stacyville. It led to a small building housing what may be Maine’s most extraordinary fly shop. Owner and retired game warden Alvin Theriault greeted us warmly as we walked past vast tables of flies. I think Theriault said he ties about 13,000 flies a year, and he has helpers too.

The essence of the North Woods enchants as the sun sets over a remote pond in the western Maine mountains. Photo by Ben EmoryOn a drive north into Aroostook County, my wife directed without warning that we turn into a nondescript driveway in Stacyville. It led to a small building housing what may be Maine’s most extraordinary fly shop. Owner and retired game warden Alvin Theriault greeted us warmly as we walked past vast tables of flies. I think Theriault said he ties about 13,000 flies a year, and he has helpers too.

Karin’s knowledge of the places and people of the North Woods is deep, having had a long career in forest conservation; she recently retired as president and CEO of the Forest Society of Maine. She already knew Theriault and his work, but I was stupefied to discover the scale of this supply source for fly fishermen.

Discussions about fly choices have led me to a much greater understanding of the life cycles of many insects, enhanced by watching a mayfly hatch on Kennebago Lake. Mayflies in all stages from birth to death and from water bottom to above the surface are prime spring food for eastern brook trout and landlocked salmon. There are flies to mimic every stage, and the correct choice from the tackle box is crucial for successful fishing.

The author and his wife, Karin Tilberg, take a shore break during a day of fishing in a high-tech drift boat made of aircraft aluminum. Photo by Scott Snell

The author and his wife, Karin Tilberg, take a shore break during a day of fishing in a high-tech drift boat made of aircraft aluminum. Photo by Scott Snell

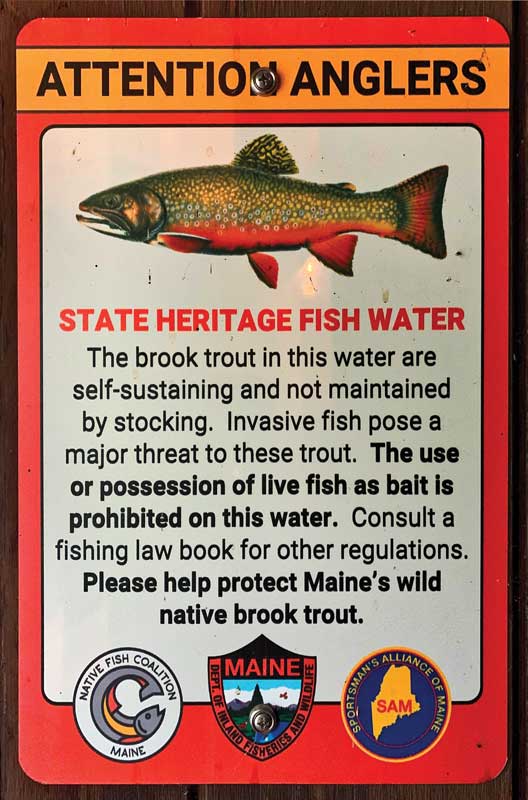

I would also learn that Maine’s North Woods are the primary refuge in the United States for eastern brook trout. These multi-hued fish of spectacular beauty are an iconic creature of Maine, as are moose, puffins, and lobsters. The state’s Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife labors hard to protect these fish, establishing State Heritage Fish Waters. These water bodies have not been stocked with eastern brook trout or Arctic char in at least 25 years. Stocking and live bait are prohibited to minimize the risk of devastation by invasive species. Maintaining the intact forested landscapes around brook trout waters is essential to their well-being too, because the forests provide nutrients and cooling shade, and they filter pollutants.

Landlocked salmon are of the same species as sea run Atlantic salmon but smaller. According to a 2014 Orvis News posting by Phil Monahan, it is now believed that landlocked salmon evolved from “certain Atlantic salmon that simply stopped going to the ocean” and are not descendants of fish trapped by the rebound of land following glacier retreat, as once believed. The thrill of hooking these high-energy fighters on a light flyrod entices many anglers to Maine’s fresh waters. I’ve landed a few up to about 12 inches, but on the East Outlet at Moosehead Lake, I found the drawbacks of inexperience. A strong strike was followed by the fish charging me. I failed to keep tension on the line, and the speeding salmon escaped.

Maine is the last stronghold for eastern brook trout, especially in areas designated as State Heritage Fish Water.Photo by Ben EmoryThough Karin has been my primary instructor, I have been privileged to spend a few days with Registered Maine Guides. When I lost that salmon, the guide was quick to point out my failure to keep the line taut. Each time we’ve gone with a professional guide I’ve made it clear at the outset I’m a beginner eager for advice. Last May I was with four different guides in two days in northwestern Maine. They rowed double-ended fiberglass Rangeley boats with an angler in the bow and stern. I received much great coaching in addition to engrossing conversation spiced with wonderful tales and laughter. And, as an avid rower, I asked to take the oars to test these excellent boats.

Maine is the last stronghold for eastern brook trout, especially in areas designated as State Heritage Fish Water.Photo by Ben EmoryThough Karin has been my primary instructor, I have been privileged to spend a few days with Registered Maine Guides. When I lost that salmon, the guide was quick to point out my failure to keep the line taut. Each time we’ve gone with a professional guide I’ve made it clear at the outset I’m a beginner eager for advice. Last May I was with four different guides in two days in northwestern Maine. They rowed double-ended fiberglass Rangeley boats with an angler in the bow and stern. I received much great coaching in addition to engrossing conversation spiced with wonderful tales and laughter. And, as an avid rower, I asked to take the oars to test these excellent boats.

The coaching I received from the guides was not completely consistent, but that is to be expected. Their knowledge, skill, and passion are remarkable and truly central to the long cultural history of “sports” coming to the Maine woods. Part of what they know is how to prepare lunch over a shoreside fire—bacon, burgers, fried potatoes, coffee. Yum!

All our fishing has been catch-and-release except during a September sojourn at delightful Nahmakanta Lake Wilderness Camps, owned by Don and Angel Hibbs. Fishing from a canoe on a remote pond, its shores kept wild and undeveloped by a conservation easement held by the Forest Society of Maine, we retained two trout to take back to the sporting camp’s kitchen. Using my mackerel-cleaning skills acquired on Eggemoggin Reach, I knelt at the edge of the pond and sliced open and scraped clean our dinner. Respectful of Wabanaki traditions of paying due homage to wildlife for the sustenance they give, we found catching and preparing these fish a reverential experience.

For me, underlying the enjoyment of flyfishing is the opportunity to be afloat, regardless of the craft, and explore new waters. We’ve cast our flies from western Maine to the Downeast Lakes and from Mount Desert Island to a remote pond north of Baxter State Park. And we’ve fished from canoes of aluminum and plastic; Rangeley boats of wood and fiberglass, powered by oars and outboards; and an aluminum Lund skiff. Even though made of modern materials, the canoes connect us to one of the Wabanaki’s greatest technological achievements, the birch bark canoe. Lightweight, able to be built and relatively easily repaired from widely available natural materials, the birch canoes were perfectly suited for Maine’s myriad waterways.

Dependent on skilled oarsmanship, a drift boat threads rapids in Moosehead Lake’s East Outlet. Photo by Scott Snell

Dependent on skilled oarsmanship, a drift boat threads rapids in Moosehead Lake’s East Outlet. Photo by Scott Snell

A totally new type of craft to me is the drift boat. Eager to give me the experience, my wife arranged for a weekend at Wilsons Camps on Moosehead Lake, next to the East Outlet. Scott Snell, owner of the camps with his wife Alison, is a noted drift-boat guide. On a gray October morning he had us afloat at first light. Drift boats are a very niche craft, designed and built for the specific purpose of fishing in fast flowing rivers and streams with navigable, although often challenging, rapids. Their origins on Oregon’s McKenzie River are beautifully documented in Roger L. Fletcher’s book Drift Boats and River Dories: Their History, Design, Construction, and Use. Today, they have become popular for fishing rivers with white water in Maine. Dory-like, they have flared sides, high freeboard, small transoms, and a lot of rocker to the bottom to facilitate sliding past rocks in rapids. Construction has evolved from boards to plywood to, in the case of Scott’s new boat from Oregon, aircraft aluminum.

The drift-boat guide rows facing the bow. How Snell used the oars to slow the boat as needed and to angle the boat to the current to control the direction of travel, especially through the boulders and foaming wildness of rapids, was fascinating. He’d anchor frequently in quieter spots, the anchor line controlled by a foot brake and the anchor dropping from an arm extending aft from the transom.

From my seat in the drift boat’s stern, I watched Karin in the bow have the most exciting, prolonged tussle with a leaping salmon that I have yet witnessed before she finally landed it into the net Snell held over the side. After a fast photo, it was released and swam off.

That energized salmon strengthened my sense of connection to the extraordinary ecosystem—to the creatures and plants of the waters and woods all around. While fishing close to forested shores, I have been as awed by the birds as the fish. Maine’s North Woods is the largest area in the United States designated by the National Audubon Society as globally significant for migratory song birds. During spring, the woods are alive with bird song.

The joy of being immersed in this natural world was encapsulated by a calm evening casting toward the circles of fish rises while standing in a Grant’s Camps’ Rangeley boat off the northeast shoreline of Kennebago Lake. Thrushes sang from the forest as the sun dropped in a sky turning from blue to purple and gold above the low pyramid of West Kennebago Mountain, which darkened with the evening’s onset. We watched other boats anchored in the same area with anglers patiently casting in the quiet, also savoring the privilege of being there. For me, flyfishing has brought a whole new connection to nature and enhanced appreciation of the imperative to sustain and properly manage Maine’s North Woods.

✮

Ben Emory splits his time between Salisbury Cove and Brooklin, Maine. He is the author of Sailor for the Wild—On Maine, Conservation and Boats, published by Seapoint Books.