All photos by Lynette L. Walther

Ken Cleaves and partner Evelyn Bell welcome visitors to Shleppinghurst.

Ken Cleaves and partner Evelyn Bell welcome visitors to Shleppinghurst.

Ken Cleaves is a man on a mission. Slowly and painstakingly, over more than four decades, he has moved earth, if not heaven, to carve out a place of wonder, a year-round garden of delights, from the remnants of a long-abandoned Maine granite quarry. Through his work he has sought harmony with nature, and he’s done it one stone at a time—and all by hand—with a manual come-along, levers, a wheelbarrow, and the like.

Over the years, his garden hermitage in Lincolnville, called Shleppinghurst, has evolved and grown, and continues to do so. The quarry, and the ledges that surround it, are the dominant features of his garden. Though it is smaller in scope than many of the quarries that dot the state, some of the elements are huge, and all qualify as heavy.

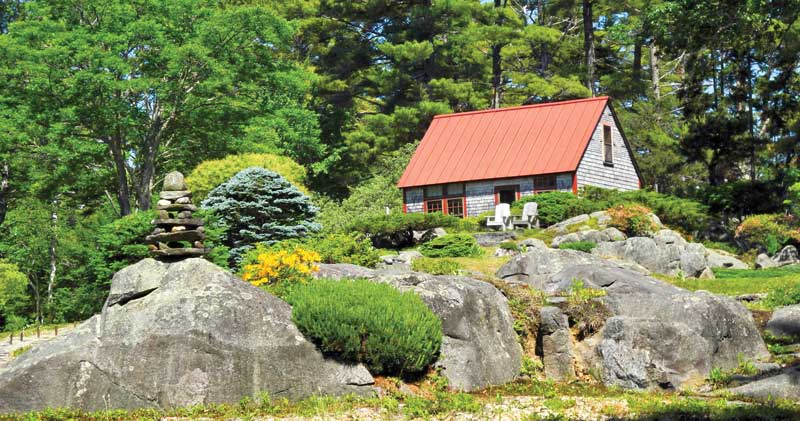

The house that Cleaves built at Shleppinghurst blends seamlessly into the landscape that surrounds it. Stone, moss, and lichen are at home here with artfully pruned trees and shrubs.

The house that Cleaves built at Shleppinghurst blends seamlessly into the landscape that surrounds it. Stone, moss, and lichen are at home here with artfully pruned trees and shrubs.

The gardens that make up Shleppinghurst were accomplished on what many would call a shoestring. Cleaves himself divided, rooted by layering branches, grew from seed, and otherwise propagated most of the growing stock that makes the setting so special. His years of tending, pruning, and training have resulted in stunningly beautiful specimen trees and shrubs that blend with and enhance the stone structures and ledges.

It is those ledges and evergreens that make the garden a sublime visitor destination any time of the year, even in the winter. “Winter is stunning here, the bones of evergreens and ledge are especially striking then, [but] the warmer seasons do give us the most pleasure,” said Cleaves’s partner, Evelyn Bell. “We love being here and sharing it.”

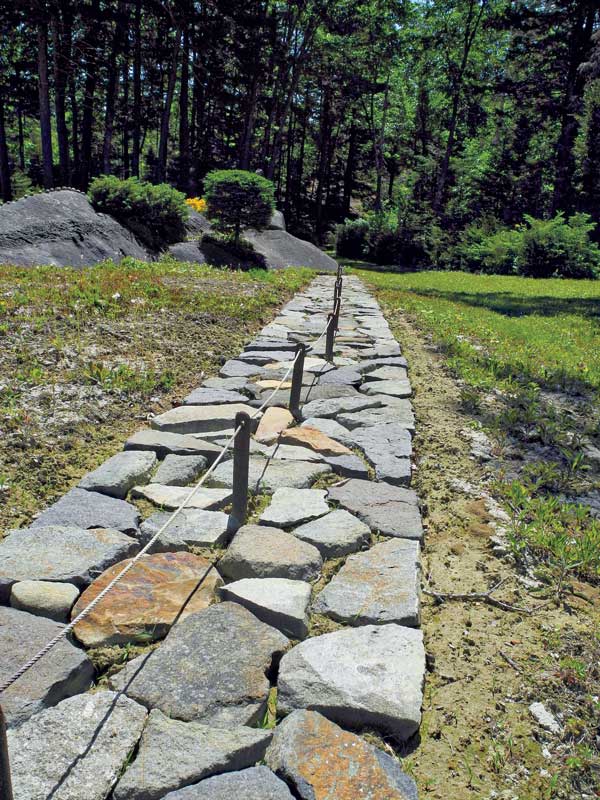

A work in progress: Cleaves uses hand tools, levers, and muscle to create a new pathway, just as he has done throughout the landscape that once was a granite quarry.

A work in progress: Cleaves uses hand tools, levers, and muscle to create a new pathway, just as he has done throughout the landscape that once was a granite quarry.

“It started out as a flower garden,” Cleaves said. That flower garden has morphed into a well-tended display that includes hundreds, if not thousands, of trees, shrubs, and perennials—many of them native—that this gardener has pruned into a calm and serene Japanese-style garden tucked into a bit of rural Maine, down a dirt road in Lincolnville.

To call Cleaves a dedicated gardener would be a trivialization. He worked as the caretaker of an extensive estate near Camden for some 30 years. He has also put his hands to a number of other trades: weaving, running a warehouse, working as a longshoreman in California, shearing Maine island sheep, and carpentry.

Subtle touches in a landscape that is rich in granite have united over time at Shleppinghurst.

Subtle touches in a landscape that is rich in granite have united over time at Shleppinghurst.

“I found out I enjoy the process of pruning,” he said, noting his childhood penchant for such work. That attraction foretold his interest in Japanese gardens, wherein 85 percent of the live components are usually evergreens that have been trimmed and trained. A native of Cape Cod, Cleaves estimated he’s spent most of his life gardening. His childhood included summer visits to Maine; he moved here full time in 1975 when he started searching for that special piece of property to fulfill his goal of creating a garden of harmony. As it turned out, that 60 acres of land he chose contained a defunct black-granite quarry.

Cleaves, who considers himself retired, now spends about 20 hours a week designing, building, tending, pruning, maintaining, and mowing more than two acres of cultivated land.

The quarry once hummed with activity and produced a high grade of black granite that could be polished to a mirror finish.

The quarry once hummed with activity and produced a high grade of black granite that could be polished to a mirror finish.

Using the granite tailings (leftovers from years of quarrying granite) and working alone, Cleaves has paved more than a mile of pathways.

They lead from ledge to ledge, from wooded glade to rocky vignette, and from open field to the quarry itself, with its shallow pool of water. The water is no longer needed to shape slabs of stone destined for headstones, but instead serves as a private pond for a host of bullfrogs.

Along the way and over the years his garden has evolved as elements have been added or existing ones enhanced.

“It’s a long wait for the stone to ‘age,’ and it is a lengthy process,” Cleaves said of a recent addition of what he calls the Sky Rock Ledge. Once unearthed by removing load after load of buckets filled with soil, the “new” ledge and boulders have been allowed time to soften as lichen or moss grows on them. To that newer section he has also added a small reflecting pool that fills with rainwater.

Several unique buildings built by Cleaves have been added to the garden, along with the home he built and that he and Bell enjoy. Among the small outbuildings is one he has dubbed a “chapel,” which includes fancy shingling that features fish, birds, and other designs.

A school of shingled cod fish swims on an outbuilding, displaying Cleaves’s creative whimsey.

A school of shingled cod fish swims on an outbuilding, displaying Cleaves’s creative whimsey.

More than a mile of stone pathways has been installed and carved into the 60-acre site.The state of Maine is rich in many things—miles and miles of incredibly scenic coastlines, prosperous forests of spruce, pine, fir, and hardwood, wild-running rivers, magnificent mountains and ranges, priceless clear blue skies that in the summertime are dotted with puffy white clouds, exuberant sunrises and sunsets, and lavish banks of fog that envelop all in a hushed magical splendor. But as unique and marvelous as all those things are, Maine is richest in rocks. Rock ledges, rocky islands, and cobble beaches are as much a signature of this state as are all the rest.

More than a mile of stone pathways has been installed and carved into the 60-acre site.The state of Maine is rich in many things—miles and miles of incredibly scenic coastlines, prosperous forests of spruce, pine, fir, and hardwood, wild-running rivers, magnificent mountains and ranges, priceless clear blue skies that in the summertime are dotted with puffy white clouds, exuberant sunrises and sunsets, and lavish banks of fog that envelop all in a hushed magical splendor. But as unique and marvelous as all those things are, Maine is richest in rocks. Rock ledges, rocky islands, and cobble beaches are as much a signature of this state as are all the rest.

If rocks themselves were a sign of affluence, then Cleaves might be considered the richest man in the state. In a conversation, he cited a strength that he imagined he has brought to light in the unearthed ledges and boulders on that rolling piece of land. Always working with the contours of the rock and ledge, he believed the land had spoken to him: “I’m the right piece of land, are you the right guy!”

Go see for yourself if he has lived up to that challenge of finding balance and accord.

✮

Contributing Garden Editor Lynette L. Walther is the recipient of the GardenComm Gold Award, Maine Press Association’s Community Columnist Award, and National Garden Bureau’s Exemplary Journalism Award, among others. She gardens in Camden.

To Get There from Here

Shleppinghurst is truly off the beaten path. To experience this sublime destination, the visitor must travel away from the coast along Route 52 past Lincolnville Center. Visitors receive detailed directions once a reservation to tour the garden has been made. The quarry is located at the end of a winding dirt road. A sign on a sawhorse as you approach informs visitors that they are entering a different plane of existence: a place of calm, a place of wonder, a place where the loudest sounds are the rustlings of leaves in the breeze, the calls and chirping of birds, and maybe the croaking of a frog.

Advance reservations are required, as mentioned. There is a two-person minimum for a visit, which includes a personal tour by the garden’s creator. During the hour-plus tour, Cleaves will point out special elements and describe and identify plants and trees. Forested areas contain understory trees such as mountain and moose maple, and native perennials and many seasonally-flowering plants as well. Walkways are stone, brick, or wood, and visitors should wear sturdy walking shoes; insect repellent is recommended because, depending on the time of year, there may be black flies or mosquitos. A fee of $15 per person is required. For reservations, call 207-763-4019.