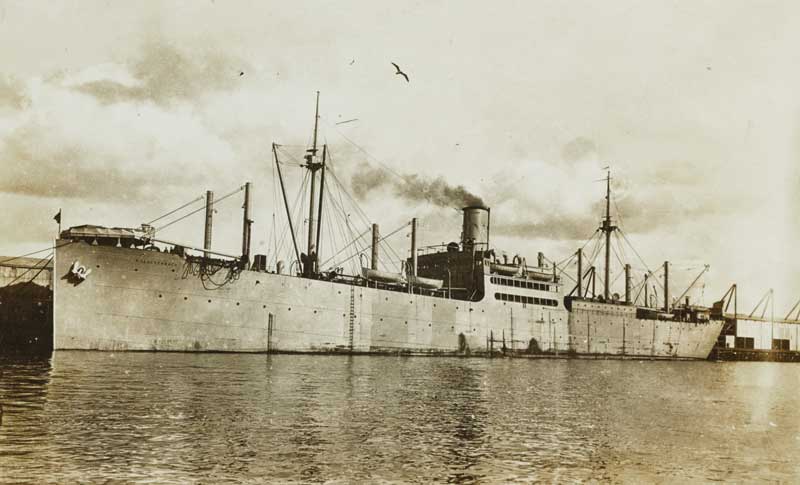

The K.I. Luckenbach is pictured in Brest, France, while serving as a troop transport in 1919. The original image is printed on postal card (AZO) stock. Photo courtesy U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command

The K.I. Luckenbach is pictured in Brest, France, while serving as a troop transport in 1919. The original image is printed on postal card (AZO) stock. Photo courtesy U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command

The morning of Monday, November 11, 1918, dawned like any other for third quartermaster Lyndhurst C. Mather on the steamer K.I. Luckenbach. According to his journal, he “went down for examination for second class quartermaster.”

However, on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month during World War I, he wrote: “When we came out of the wardroom, we saw all the ships with all kinds of ensigns flying and upon inquiry we found that a signal came which told about cessation of hostilities. We did not exactly [know] what this might mean as we had heard about a peace counsel so we waited for night to get full particulars. In the afternoon the French cruiser, which had been escorting us with two French destroyers, which had come out from Brest to escort us in to St. Nazaire suddenly got up full speed and disappeared over the horizon. We expected the convoy would break up and proceed independently to destination but I guess all the submarines had not been notified and there was still danger...If we had a couple of quarts apiece we would celebrate tonight but there seems to be no chance until we reach St. Nazaire. I’ll bet you folks are sure celebrating tonight (with bells).”

The K.I. Luckenbach originally launched in 1917 at the Fore River Shipbuilding Co. in Quincy, Massachusetts. The U.S. Navy acquired it on August 8, 1918, to serve as a cargo transport supplying the American Expeditionary Force in France. Mather, and the steamship, left New York on October 26, 1918 with “The decks...covered with aeroplanes and artillery trucks and we have a plank platform rigged over them to make it easier to get to the guns.” They traveled in convoy to France to avoid submarine attacks.

Troops crowd the K.I. Luckenbach’s foredeck, as seen from her bridge during a voyage from France to the United States in April, 1919. The original photograph is printed on postal card (AZO) stock. Photo courtesy U.S. Naval History and Heritage CommandAlthough Mather writes in his journal that he and the ship never felt threatened by submarines, submarines were a constant threat to convoys. When Mather entered the Straits of Gibraltar, he noted in his journal that the U-boat Spartel Jacke, named for Cape Spartel in Morocco, shot up several convoys. According to a January, 1919, article in Sea Power magazine, Spartel Jacke and its German compatriots focused their attacks on merchant shipping and on ships like the Luckenbach that were commissioned to carry military supplies. The U-boat relayed to its victims the position of the nearest patrol boat for rescue and even radioed the British admiral at Gibraltar to request motor launches be sent to pick up survivors.

Troops crowd the K.I. Luckenbach’s foredeck, as seen from her bridge during a voyage from France to the United States in April, 1919. The original photograph is printed on postal card (AZO) stock. Photo courtesy U.S. Naval History and Heritage CommandAlthough Mather writes in his journal that he and the ship never felt threatened by submarines, submarines were a constant threat to convoys. When Mather entered the Straits of Gibraltar, he noted in his journal that the U-boat Spartel Jacke, named for Cape Spartel in Morocco, shot up several convoys. According to a January, 1919, article in Sea Power magazine, Spartel Jacke and its German compatriots focused their attacks on merchant shipping and on ships like the Luckenbach that were commissioned to carry military supplies. The U-boat relayed to its victims the position of the nearest patrol boat for rescue and even radioed the British admiral at Gibraltar to request motor launches be sent to pick up survivors.

The U.S. Navy instituted a convoy system in response to the attacks on troopships, and ocean and coastal cargo ships, like the Luckenbach, headed to Brest and St. Nazaire, France. A battleship, armed cruiser, or protected cruiser, acted as an ocean escort to the convoy of one to 18 transports; at least two destroyers guided the convoy through the submarine zone along the coastlines. Due to fuel capacity limits of U-boats and the hit-or-miss nature of finding merchant ships at sea, the U-boats focused on shipping lanes within 300 miles of the European and American coastlines, known as the “submarine zone.”

Lyndhurst C. Mather wrote this journal entry for World War I Armistice Day, November 11, 1918. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum.The USS Drayton, a 1909 Bath Iron Works-built destroyer, met the Luckenbach off France and guided it into the Bay of Biscay.

Lyndhurst C. Mather wrote this journal entry for World War I Armistice Day, November 11, 1918. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum.The USS Drayton, a 1909 Bath Iron Works-built destroyer, met the Luckenbach off France and guided it into the Bay of Biscay.

The U.S. Navy grouped ships into convoys based on their similar cruising speeds; Mather notes in his journal that his captain grew impatient when fellow convoy members could not maintain the designated speed and slowed everyone down.

To frustrate the U-boats’ reliance on shipping lane choke points, the convoy zigzagged its way across the ocean, with the coastal destroyers making exaggerated zigzags, and no two convoys followed the same route.

Ship navigation lights were another hazard for detection, so the convoys traveled without lights, as mentioned in Mather’s journal. Communication was key to knowing the location of other convoys, as well as movements within one’s own convoy. The convoy system reduced the German strategy of attacking ships individually and at their leisure, deterred by the threat of counterattack by destroyers. It also ensured a faster rescue should a ship be torpedoed.

Track chart of the steamer K.I. Luckenbach in November 1918 superimposed on section of “North Atlantic Ocean, Sheet II” chart #22, published by the U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office in 1869. 118, Gift of Captain Wellington Barbour. Like with any war, it took time for word of the peace to reach all combatants. The threat of submarines continued to be an issue for the Luckenbach after the official Armistice, but Mather began seeing signs of the Allies celebrating.

Track chart of the steamer K.I. Luckenbach in November 1918 superimposed on section of “North Atlantic Ocean, Sheet II” chart #22, published by the U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office in 1869. 118, Gift of Captain Wellington Barbour. Like with any war, it took time for word of the peace to reach all combatants. The threat of submarines continued to be an issue for the Luckenbach after the official Armistice, but Mather began seeing signs of the Allies celebrating.

He wrote, “Tuesday, November 12, 1918...Two more destroyers came to meet us in the morning and in the pm 4 more came. We are now well protected. You see all the submarines have not been notified yet and there is still danger.

“Wednesday, November 13, 1918...We are getting close to land…It is not so dangerous to flash a light...We did not get any press news this watch as usual but I guess by the reports from the night before that the war is not over yet by any means...We got orders from the commodore saying the convoy was going to break up at three pm... All ships bound for St. Nazaire and Nantes were to go with the American destroyer into Quiberon Bay.

“Friday, November 15, 1918...We started up the bay for St. Nazaire...On the way up we could see the American soldiers where they were encamped on the banks along the shore line. Everything is decorated up to the million, I guess there is some rejoicing over on this side. We did not get shore liberty and will not until we tie up alongside the dock.”

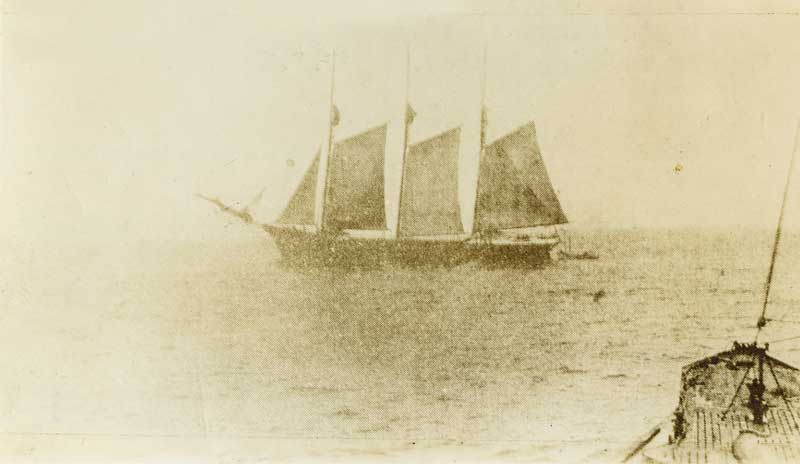

The schooner Hattie Dunn is about to be sunk by the German U-boat U-151 (bow visible in lower right corner of photo) in 1918. Foss Collection, LB1985.97.1.11Despite the end of the war, there was still more work for the Luckenbach in Marseilles on the Mediterranean. The threat of submarines may have been over, but now the threat of sea mines hampered free movement.

The schooner Hattie Dunn is about to be sunk by the German U-boat U-151 (bow visible in lower right corner of photo) in 1918. Foss Collection, LB1985.97.1.11Despite the end of the war, there was still more work for the Luckenbach in Marseilles on the Mediterranean. The threat of submarines may have been over, but now the threat of sea mines hampered free movement.

Mather wrote, “Saturday, November 16, 1918...We are now loaded for Marseilles which will take 6 or seven days yet until we are able to celebrate our victory...All the lights are to be lit on the whole trip so I guess all the submarines have been notified at last.

“Sunday, November 17, 1918...We go from Cape Finistaire [sic] to Cape Vincent and land is in sight...until this afternoon and then we change course and do not see land for quite a while again...The Captain told us tonight that just before the war ended the submarines had planted thousands of mines off the different coasts. Probably in a year’s more time if the war had lasted it would not have been safe to have gone in any port without mine sweepers.

“Friday, November 22, 1918...In the afternoon we passed the city of San Sebastian only three miles on our port side and also a British ship going in. This proves to all who doubted that the war is indeed over.”

Despite the delay to reach shore and celebrate, when he does so 13 days after the Armistice, Mather’s report is rather disappointing:

“Sunday, November 24, 1918...I went on land for the first time in 30 days exactly...I was up to the Army YMCA but is it very poorly represented in the line of comforts and supplies, maybe it is because they have planned to move this QM base to another port now that the war has ended.”

Oh, and that exam Mather took the day of the Armistice? He passed.

✮

Cipperly Good is the Richard Saltonstall Jr. Curator of Maritime History at Penobscot Marine Museum. This article first appeared in a 2023 museum newsletter.