Hollow bows, rare in a catboat, are common to designers Hallett and Herreshoff.

Hollow bows, rare in a catboat, are common to designers Hallett and Herreshoff.

We are in the midst of an affordability crisis that conspires to limit the joys of sailing, so for this month’s column, I set out to review a small boat, one that is remarkably high in sailing satisfaction and affordable at the same time.

I am 80, but I still work, putting in hours at Elk Spar and Boat Shop on Mount Desert Island. My days of rassling with hot heavy steamed timbers are done, so most of my jobs involve rigging systems and inventive ways of making racing boats faster and easier to manage.

A used, affordable Handy Cat, looking like new, speeds across Bass Harbor.Last winter a fellow named Alan McDuffie came along with a fiberglass catboat on a trailer. I am assuredly not a cat person, but I am definitely a catboat lover. My twin brother, Chuck, my best friend, Bobby McNaught, and I sailed the first race of my life aboard a Beetle Cat a very long time ago. I shall never forget that. Three boys inside a curvaceous wooden cocoon, just 12 feet long and 6 feet wide, with what seemed at the time to be a towering gaff-rig sail. I believe we came in last. But from that day on, I’ve always loved a catboat.

A used, affordable Handy Cat, looking like new, speeds across Bass Harbor.Last winter a fellow named Alan McDuffie came along with a fiberglass catboat on a trailer. I am assuredly not a cat person, but I am definitely a catboat lover. My twin brother, Chuck, my best friend, Bobby McNaught, and I sailed the first race of my life aboard a Beetle Cat a very long time ago. I shall never forget that. Three boys inside a curvaceous wooden cocoon, just 12 feet long and 6 feet wide, with what seemed at the time to be a towering gaff-rig sail. I believe we came in last. But from that day on, I’ve always loved a catboat.

I was still in the Navy when I heard that Bobby was killed in action in Vietnam. I can still see him now, though, his arm crooked over the tiller, with the Beetle’s mast hoops clicking away each time we tacked…

Sorry, I was caught aback. As I said, I always loved a catboat, and when McDuffie backed his fiberglass cat into our shop, I employed my critical eye on that hull, the curved coaming that went right around, and the three varnished spars of a nice gaff rig. All catboats large or small, with the possible exception of Gil Smith designs (see “A Faster Breed of Cat,” January/February 2019, MBH&H Issue 156), are remarkably similar—beamy vessels, half as wide as they are long—the only significant variation usually being freeboard. But this one was different. A touch of pretty wineglass in the transom, but most conspicuous to my eye was the bow. I would describe the fore portion of this hull as normal catboat blended with Herreshoff-style hollow sections extending well aft.

“It’s a Handy Cat,” McDuffie said. “Designed by Merle Hallett.”

The original rig had a free standing mast; the new treatment, which includes the fabricated mast tabernacle, required side and head-stays.

The original rig had a free standing mast; the new treatment, which includes the fabricated mast tabernacle, required side and head-stays.

Although I was very familiar with Hallett and always greatly admired the man, until that moment I never realized he was a yacht designer. I did know he was the fellow who grew Handy Boat in Falmouth into a company focused on repairs, storage, boatbuilding, and sailmaking, with 300 reliable moorings, and the best restaurant a short sail north of Portland.

Although I was very familiar with Hallett and always greatly admired the man, until that moment I never realized he was a yacht designer. I did know he was the fellow who grew Handy Boat in Falmouth into a company focused on repairs, storage, boatbuilding, and sailmaking, with 300 reliable moorings, and the best restaurant a short sail north of Portland.

Hallett died just two years ago, after having enjoyed a larger-than-life time steeped in the world of sailing, mostly racing. I had won the Maine State Sailing Championship twice, and I know Hallett won it a few more times than that. I often ran into him in the boating world, though not in races—we never competed for the championship in the same year.

One time I was in the U.S. Virgin Islands working at Dick Avery’s Boathouse and in walked Hallett. He and Avery were both Pearson Yachts salesmen, and the builder’s East Coast sales meeting was convened under the palm trees at the Quarterdeck Restaurant. It was impossible to meet Hallett and not instantly like him. When I talked to him I felt a certain affinity, probably a mixture of love of sailboat racing and love of Maine. And when we spoke about yacht design, I noticed that he talked with his hands, in the secret language of an artist. That was in the winter of 1980, and I later learned that at that time he had never yet actually designed a boat.

One of his sons, Jay Hallett, told me that the Handy Cat was originally sold by Cape Dory Yachts, and was an instant success. Over 100 were built before the molds were sold to Nauset Marine, on Cape Cod, which built 172 more. Next the molds came to Maine—to Handy Boat. This was where McDuffie’s boat came from. A couple dozen hulls were launched, and many stayed on our coast. Then around the year 2000, Stroudwater Boatworks, in Portland, Maine, continued production after making some small improvements to joinery work and fittings.

But back to McDuffie and his Handy Cat. I learned he also owns a Marshall Sanderling catboat, which is a “big” 22-footer with a commodious non-standup cabin with bunks and a rudimentary galley (see “Prowling the Coast in a Catboat,” July/August, 2020, MBH&H issue 165). His Sanderling could be launched by two people from the trailer and rigged, because it has an above-decks mast hinge called a tabernacle. This is a beautifully engineered device that allows mast, boom, and gaff to all fold down and stack, sail still attached, for trailering.

Hallett’s painting is quintessential Maine Coast.

Hallett’s painting is quintessential Maine Coast.

McDuffie plans to only use his little 14-foot Handy Cat for inshore day sailing, so his mandate to Elk Spar was for us to design and build an affordable way to fold the spars similarly, requiring only the exertions of just a single-hander. (The unstayed spar of most Handy Cats is stepped with its butt-end lowered down into a hollow pipe glassed into the bow of the boat.)

Jim Elk, founder of Elk Spar, and I love this sort of challenge. We did consider doing a miniature of the optional spar-hinge used on the Sanderling, but it didn’t take long for us to realize that the “affordable” mandate was impossible to achieve. So, I did a mechanical drawing of a stainless-steel tabernacle, then built a quick hot-glued-plywood mockup, and farmed it out to a few local welders.

I always try to get three or four bids on a job, but due to time constraints, this time I only elicited two. The low-ball price came in from Nautilus Marine in Trenton, and the waterjet-cut, precisely perfect fabrication cost us well under $300. (The other bid was five times that, and I don’t wish to say what the bigger and glorious Sanderling hinge costs.) Our work on McDuffie’s Handy Cat also included putting three stays on the mast, installing a hefty bronze folding motor mount for an electric outboard, and a lot of fun-to-accomplish minor details.

I live in a place overlooking Bass Harbor, where this catboat sails on many evenings. It’s always singlehanded. I think I know what magic Merle Hallett was privy to. He understood that catboats work best when they’re hefty. Maybe the heavier the better. (Handy Cats tip the scales at about 800 pounds fully outfitted and rigged.) And he put a huge centerboard in the boat. When you can’t have an ideal airfoil, the bigger the plate the better. No matter how big the board, when it’s retracted the Handy Cat can sail in a foot of water and bash right up onto a rocky beach. It is an ideal Maine boat, in fact. You won’t need reef points very often, but you’d be a fool not to have them.

Nobody expects it but catboats are fast! I recall one named Silent Maid that was all of 33 feet long that sailed against me in an early Eggemoggin Reach Regatta. It won the whole event by 38 minutes on corrected time. Granted there was a football team on the rail and there was prodigious weather helm, but don’t for a minute think that beamy equates to slow in the catboat world.

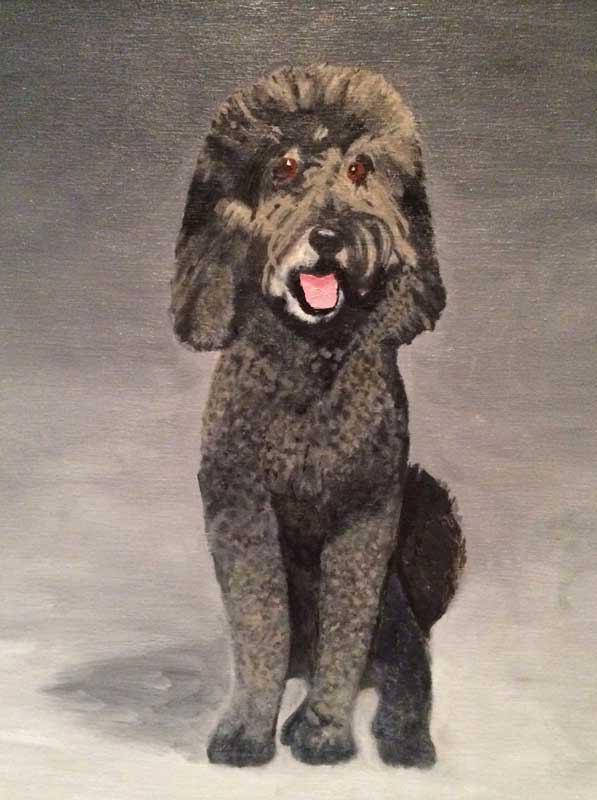

Merle Hallett had an eye for dogs...and cats.Late this past summer I watched McDuffie, and his sister from France, on a different evening, sailing that Handy Cat to windward through the lobsterboat fleet. She stood up straight and didn’t make a bit of leeway. I’ve always maintained that a pretty boat is usually a great performing boat, so thinking backward, and recalling the sculpture of the hull, I gave thought to my speculation that maybe Merle Hallett the yacht designer might have had the heart and soul of an artist.

Merle Hallett had an eye for dogs...and cats.Late this past summer I watched McDuffie, and his sister from France, on a different evening, sailing that Handy Cat to windward through the lobsterboat fleet. She stood up straight and didn’t make a bit of leeway. I’ve always maintained that a pretty boat is usually a great performing boat, so thinking backward, and recalling the sculpture of the hull, I gave thought to my speculation that maybe Merle Hallett the yacht designer might have had the heart and soul of an artist.

You can buy a Handy Cat at an affordable price on the used market, if you’re lucky, and store it affordably on a trailer. On that account, “Handy Cat” made sense.

As for the boat’s designer, I don’t know if it was son Richard or son Jay who informed me that late in his life—after having been a musician, top skier, Bermuda race winner, singer, entrepreneur, inventor, yacht sailor and broker, beloved father, and dog (rather than cat) appreciator—Merle Hallett, not to my surprise, took up painting. Picture painting, that is.

I’ve always said yacht design is a blend of art and science, and the best yacht designers in history were nearly always artists. If you have any questions about my contention that you can judge a designer’s competence based upon his art, consider the two Hallett paintings that appear with this story. Like the Handy Cat, they look good.

✮

Contributing editor Art Paine is a boat designer, artist, and writer who lives in Bernard, Maine.

Handy Cat Specifications

Beam: 6' 8"

Draft board up: 1' 2"

Displ. empty: 750 lbs.

Draft board down: 4'

Sail Area: 160 sq. ft.

Designed by: Merle Hallett