George Williams is lead mechanic and stands ready to repair all machinery, old and new. Courtesy Edward H. Best Co.

George Williams is lead mechanic and stands ready to repair all machinery, old and new. Courtesy Edward H. Best Co.

The casual summer visitor to present-day Camden might be surprised to learn that, in addition to being a fashionable tourist destination, historically it was also a bustling, industrial, very blue-collar town where manufacturing was king. In addition to sawmills and gristmills, Camden had carriage, sash, and blind factories, and blacksmith shops. Shipyards covered the waterfront, and built vessels ranging from launches and dories to commercial schooners to military craft in war time to elegant custom yachts. There were foundries that produced pumps, blocks, winches, windlasses, derricks, dead-eyes, anchors, and the famous Knox Gasoline Engine.

And, there were the woolen mills. The mills were here because the town is blessed with a renewable resource: the 3-mile-long Megunticook River, where dams produced ample waterpower to run mill machinery.

The Knox Woolen Mill in Camden, Maine, as it was in 1870. Courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

The Knox Woolen Mill in Camden, Maine, as it was in 1870. Courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Perhaps the best known of the mills was the huge Knox Woolen Mill, recognizable today by its tall smokestack in the middle of town. Running from the mid 1800s until 1988, the mill used wool from surrounding farms as well as fiber shipped from around the world to produce the woolen felts used in the manufacture of paper and other goods. The mill was an economic powerhouse and a major employer in the region, and its machines produced woolen felts for the Edward H. Best Co., originally located in Massachusetts. At the time, the Best Co. was a broker that bought the mill’s output and resold it.

The late 20th century brought economic change, however, and the Knox Mill, like many other contemporary textile operations in Maine, was faced with either sale or closure. In the end, it experienced both; most of its assets were sold to the Mt. Vernon Co. of South Carolina in 1982, which, in turn, closed the Camden facility and moved its operation out of state in 1988.

While the mill building itself was sold for modern conversion, the historic 19th-century machinery, which created tubular woven woolen felt sleeves and produced industrial belts, remained in coastal Maine.

As with any business, the secret sauce is the people who have passion for the product. Seeing potential where others did not, the looms and equipment were purchased in 1987 by John Rosseel of Abington, Massachusetts, who at the time was owner of Edward H. Best. The machinery was moved to a nondescript commercial building in Thomaston under a new Rosseel-owned company named Best Felts around 2009. The classic machines—and many of the employees who operated them—once again began cranking out the mills’ traditional product line: endless woven tubular felt belts, and roller covers called jackets, used in manufacturing and polishing applications.

Company president David Erb at the roller top inspection table. Photo by Greg Rössel

Company president David Erb at the roller top inspection table. Photo by Greg Rössel

To help manage this new/old enterprise, Rosseel hired Shirley Hocking in 1987 to assist in the business as an administrative assistant. Nearly 40 years later, she progressed to become the company vice president and manager—all while raising two children. The small-scale business has done well serving specialty niche markets and large industrial manufacturers around the world.

But in the 21st century, a skeptic might ask, “Why use sheep, yarn, and felt—isn’t there something better?” It turns out that woolen belts have unique properties that are hard to replicate with other more modern materials. Commercial bakers use them in conveyor belts for bread baking (the loaves don’t stick to wool). Wool belts have been used for robotic polishing of cathode ray tubes (a very big business for Best in past years), guitars, and knee and hip joint devices. Wallpaper is printed with woolen rollers and wool is tops for applying adhesives in furniture manufacturing. But wait, there’s more: liquid filtration, air filtration, wicking, padding, roll coverings for glass and metal manufacturing. Wool, it turns out, is a sort of a natural wonder product.

When John Rosseel died in 2021—in his 90s and still involved—there were questions about the mill’s future. Running a 19th-century felt factory is not everyone’s cup of tea, after all. Enter entrepreneurs John Karp and David Erb. These quintessential “happy warriors” of small business are partners in a company called Windward Ventures.

Karp, who serves as CEO, is a serious company builder. He is a business coach with Maine Manufacturing Extension Partnership and an Entrepreneur in Residence at the Maine Technology Institute. He has expertise working with startups and turnarounds—businesses ranging from Bourgeois Guitars, with its high-performance acoustic instruments, to those that develop and market medical devices.

Retired from the Air Force with the rank of major, Erb is the tech guy. He was formerly director of research and development at Tex-Tech Industries in Monmouth, Maine, and senior research and development program manager at the University of Maine’s Advanced Structures and Composites Center. Erb has expertise in felt and composites as well as early training on vintage metal lathes. Equally important, he was also a long-term friend of Rosseel’s, so he was familiar with the operation. He took over as president.

Heidi Bishop, Karp’s wife, rounded out the team, serving as the company treasurer.

With the company’s skilled work force and the indomitable Hocking, who has been running the shop for 38 years, willing to stay on, they took the plunge and purchased Edward H. Best and Co.

The shuttle looms at Best Co. can make many widths of product, using up to 5,000 leads, or warps (the pieces of yarn shown). Photo by Greg RösselTouring the Mill

The shuttle looms at Best Co. can make many widths of product, using up to 5,000 leads, or warps (the pieces of yarn shown). Photo by Greg RösselTouring the Mill

From the other side of the window that looks onto the shop floor comes the once familiar cacophony of Maine textile mill machinery—a sound now mostly heard on industrial museum recordings. Erb smiles, as this is clearly music to his ears. This is no theme park though. These machines are about 21st-century business.

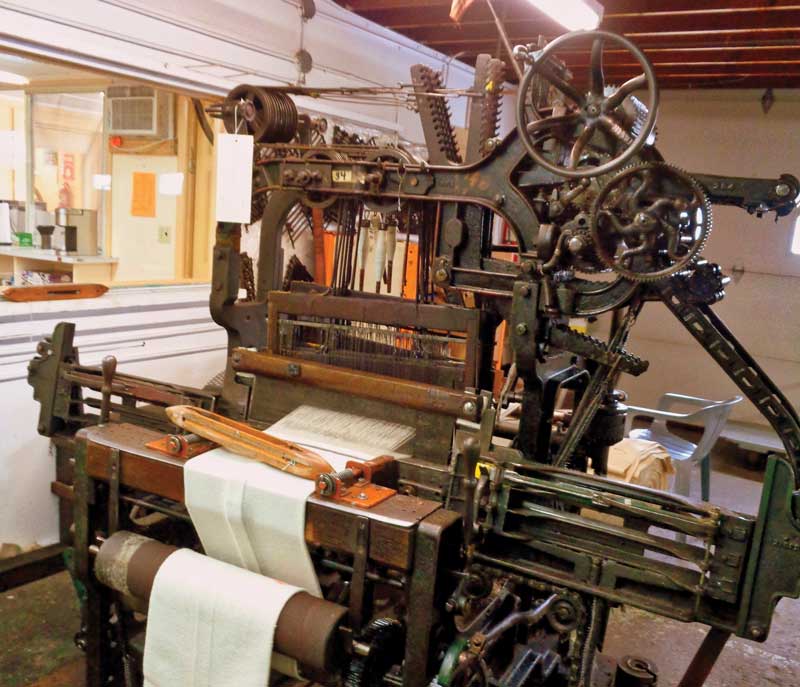

The Crompton & Knowles looms are remarkable devices, reminiscent of steam locomotives of the same era. Massive iron gears, pawls, and wheels, levers, wooden pitman arms, spools and bobbins are all intertwined. While they have been converted from water power to electricity, they remain the same effective machines, excelling in doing their job. In addition to their skilled operators, the devices are controlled by a repeating chain, which contains a regular series of rods with discs that together looks, remarkably, a bit like a floppy abacus. You could say that it is a 19th-century bit of computer programming. Like in a player piano or music box, the loom reads the placement of the discs and spacers as the repeating chain runs by and produces a particular pattern in the finished woven product. There is one of these chains for each pattern. The techniques of endless weaving and 3-D weaving, which adds significant depth or thickness, are promoted as cutting-edge today, but these machines have been doing it for over 100 years.

There is an art and a science to the working with the historic looms and equipment. Courtesy Edward H. Best Co.The operators and maintenance crew must be one with the temperament of these straightforward yet elaborate machines. The vintage instruction manual admonishes that “loom fixers should be properly trained in the art of maintenance…The age-old practice of eye-sighting, measuring with the fingers, and rule-of-thumb theory cannot be successfully applied to (these) modern high-speed looms.” Written in a somewhat less politically sensitive era, the manual brusquely opines that if employee instructions “are applied in an intelligent manner, then successful operation of your looms will be obtained.”

There is an art and a science to the working with the historic looms and equipment. Courtesy Edward H. Best Co.The operators and maintenance crew must be one with the temperament of these straightforward yet elaborate machines. The vintage instruction manual admonishes that “loom fixers should be properly trained in the art of maintenance…The age-old practice of eye-sighting, measuring with the fingers, and rule-of-thumb theory cannot be successfully applied to (these) modern high-speed looms.” Written in a somewhat less politically sensitive era, the manual brusquely opines that if employee instructions “are applied in an intelligent manner, then successful operation of your looms will be obtained.”

Erb notes that the machine upkeep is indeed constant. “The big parts don’t break but the small ones do,” he said, adding that the mechanics must understand the whole machine. The factory maintains a stock of parts and the shop, where other replacement pieces are fabricated out of iron, wood (mostly maple), or leather.

Learning all the machines and devices presented a sharp curve but Erb has taken to it like a duck to water. Looms aren’t the only mechanisms in the shop. The wooden hammer mill still retains some of the personality of its former operators—the wooden frame has carved into it the World War II slogan, “Keep Em Flying.”

George Williams loads the massive felt dryer. Photo by Greg RösselThen there is the industrial-strength, riveted-construction centrifuge, whose purpose is analogous to the “spin cycle” of a washing machine. It’s used to extract water from the soaked woven product.

George Williams loads the massive felt dryer. Photo by Greg RösselThen there is the industrial-strength, riveted-construction centrifuge, whose purpose is analogous to the “spin cycle” of a washing machine. It’s used to extract water from the soaked woven product.

To assure flawless product quality, there is a large wooden roller-topped fabric inspection table behind which Bob Cratchit, from Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, would have been right at home toiling.

In order for the finished felt jackets to shrink tightly around machine components like rollers and cylinders, they must be stretched or expanded from the inside. To accomplish this, the mill employs a technique as old as Archimedes: use of the inclined plane, or in this case, planes. The process involves a series of wooden devices used to stretch and dry the product, a technique which has yet to be effectively duplicated with modern equipment. The wood and wool are synchronous in the way they dry, and this creates a stable and consistent product that shrinks extremely tightly circumferentially to the mating machine components.

Some of the company's looms date back 100 years. Note size of the hardwood shuttle shown. This loom slides back and forth several inches as it runs. Photo by Greg RösselWhich brings us from ancient history to an anomaly in the factory: the lone textile machine on the floor that could be considered the great grandchild of the venerable Crompton & Knowles machines. It’s a thoroughly modern, state-of-the-art loom that can produce felted tubes made of Kevlar, Nomex, and other advanced materials. These are used to insulate parts of jet engines, including high-tech composites, along with serving as protective products for cut resistance and many other applications.

Some of the company's looms date back 100 years. Note size of the hardwood shuttle shown. This loom slides back and forth several inches as it runs. Photo by Greg RösselWhich brings us from ancient history to an anomaly in the factory: the lone textile machine on the floor that could be considered the great grandchild of the venerable Crompton & Knowles machines. It’s a thoroughly modern, state-of-the-art loom that can produce felted tubes made of Kevlar, Nomex, and other advanced materials. These are used to insulate parts of jet engines, including high-tech composites, along with serving as protective products for cut resistance and many other applications.

Best’s plans are to expand into numerous types of technical materials and expand its products through the new marketing and sales efforts of EHB Engineered Textiles.

But perhaps the fact that the Nomex/Kevlar loom exists side-by-side with the wooden wedges and the venerable Crompton & Knowles looms is a metaphor for the approach Edward H. Best Co. takes toward the utilization of technology. It’s really about wise and practical use of machinery that works no matter what year it was invented—another variation of the old saying, “anything old can be new again.”

✮

Greg Rössel lives in Troy. He is a boatbuilder, an instructor at the WoodenBoat School and its “Mastering Skill” video series, an author, and the host of “A World of Music” radio show on WERU FM.