Lauren Beveridge of Scout + Bean with one of the impressive rope baskets she designs and makes. Courtesy Lauren Beveridge

Lauren Beveridge of Scout + Bean with one of the impressive rope baskets she designs and makes. Courtesy Lauren Beveridge

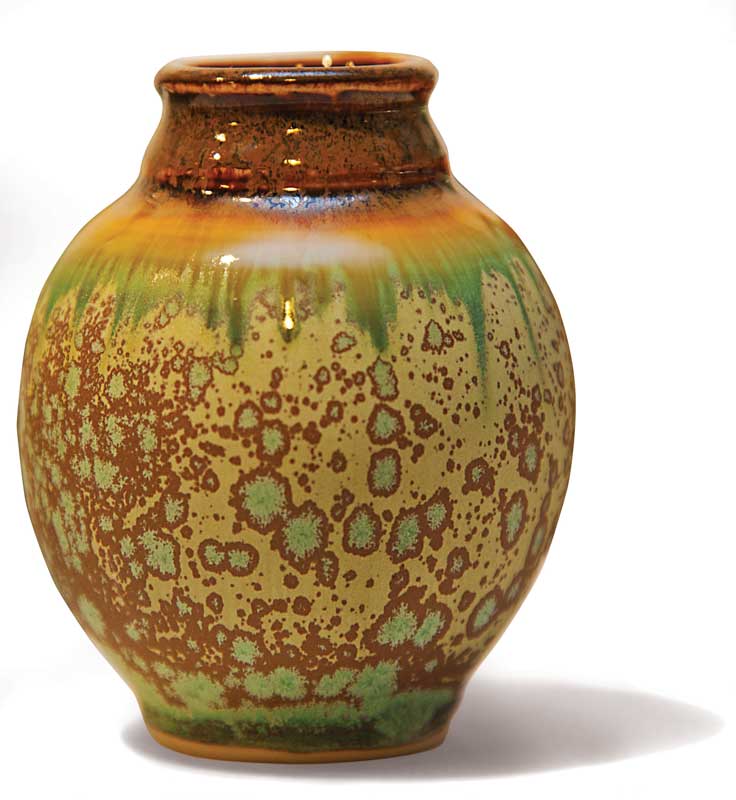

A vessel made by Mary and Joe Devenney. Courtesy Mary and Joe DevenneySome say it was the COVID pandemic that drove them to it. Others say it was a random course or a chance meeting at one of Vacationland’s many fairs or shows that inspired them to turn their passion into a profitable business. But no matter how they got their start, Maine’s maker community is a busy bunch. They work year-round to produce the arts, the crafts, and even the wind-blown whirligigs that sell like hotcakes these days online, in galleries, at holiday events, and at gatherings like September’s Common Ground Country Fair in Unity, Maine.

A vessel made by Mary and Joe Devenney. Courtesy Mary and Joe DevenneySome say it was the COVID pandemic that drove them to it. Others say it was a random course or a chance meeting at one of Vacationland’s many fairs or shows that inspired them to turn their passion into a profitable business. But no matter how they got their start, Maine’s maker community is a busy bunch. They work year-round to produce the arts, the crafts, and even the wind-blown whirligigs that sell like hotcakes these days online, in galleries, at holiday events, and at gatherings like September’s Common Ground Country Fair in Unity, Maine.

The fair, just two years shy of 50 and run by the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, is a showcase for a vast cast of vendors selling wares from food to furniture to farm products and livestock. But it’s just one in a seemingly endless array of outlets for creativity when it comes to things made in Maine. Collectively, the state is a vibrant creative marketplace offering makers endless ways to sell their wares.

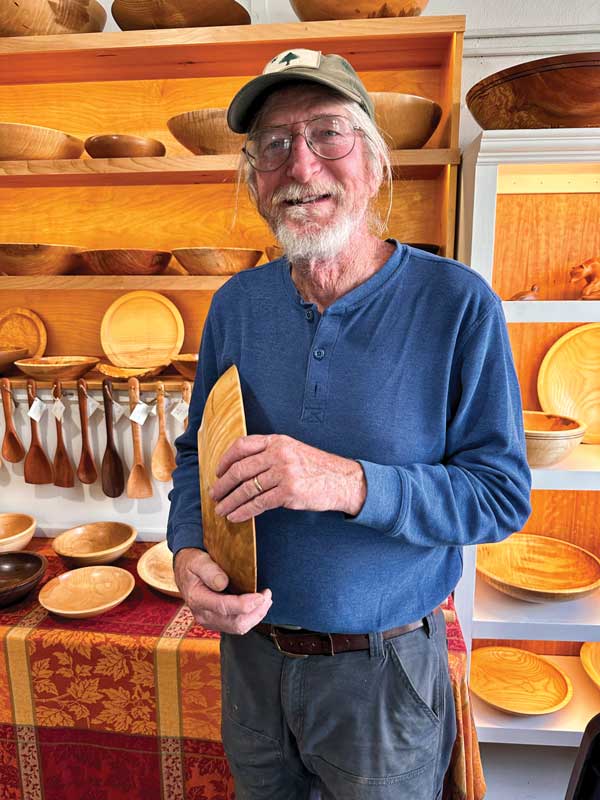

Woodcarver Ken Wise with some of his wares. Courtesy Ken WiseNow a seasoned woodcarver in the Brunswick area, Ken Wise recalls that as a carpenter in 1990, “I began taking adult-ed classes in woodcarving from Wayne Robbins, a very talented wildlife carving artist, and learned that woodworking isn’t all boxes, straight lines, and square corners. This opened up a world of possibilities and my work became more creative and inspired by the natural world. Over time I became more confident and the part-time side hustle became a more important part of my life. I started taking woodturning classes, including the Woodturning Intensive at the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship in Rockport, which enabled me to make wooden bowls and turned kitchenware to expand my product line. In 2014 I began doing this work full time in my shop and stopped doing carpentry jobs. With a great deal of support and encouragement from my wife, Julie, we found a way to allow me to focus on this work and contribute to the family household income.”

Woodcarver Ken Wise with some of his wares. Courtesy Ken WiseNow a seasoned woodcarver in the Brunswick area, Ken Wise recalls that as a carpenter in 1990, “I began taking adult-ed classes in woodcarving from Wayne Robbins, a very talented wildlife carving artist, and learned that woodworking isn’t all boxes, straight lines, and square corners. This opened up a world of possibilities and my work became more creative and inspired by the natural world. Over time I became more confident and the part-time side hustle became a more important part of my life. I started taking woodturning classes, including the Woodturning Intensive at the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship in Rockport, which enabled me to make wooden bowls and turned kitchenware to expand my product line. In 2014 I began doing this work full time in my shop and stopped doing carpentry jobs. With a great deal of support and encouragement from my wife, Julie, we found a way to allow me to focus on this work and contribute to the family household income.”

Kate Tallberg of the Linnea Company displays three of her handmade dolls. Courtesy Kate TallbergKate Tallberg, 39, is the owner and sole maker for The Linnea Co., where she creates heirloom-style diverse dolls by hand in Warren, Maine. Tallberg began making dolls in 2021 and participating in shows in 2022. Having been featured on “Good Morning America,” Tallberg’s dolls offer a unique and traditional alternative to the many mass-produced ones on the market. She said 2024 will be her second showing at the Common Ground Fair, and she adds that she’s also launched a company that creates bags and accessories from would-be refuse including lumber tarps and malt bags as another sustainable revenue source.

Kate Tallberg of the Linnea Company displays three of her handmade dolls. Courtesy Kate TallbergKate Tallberg, 39, is the owner and sole maker for The Linnea Co., where she creates heirloom-style diverse dolls by hand in Warren, Maine. Tallberg began making dolls in 2021 and participating in shows in 2022. Having been featured on “Good Morning America,” Tallberg’s dolls offer a unique and traditional alternative to the many mass-produced ones on the market. She said 2024 will be her second showing at the Common Ground Fair, and she adds that she’s also launched a company that creates bags and accessories from would-be refuse including lumber tarps and malt bags as another sustainable revenue source.

Tallberg said she largely does shows solo, and even brings her sewing machine (when her booth has electricity available) so that she can continue to work while selling her wares.

“I am never truly on my own. I have met so many wonderful people doing the different fairs in Maine. Someone always lends a hand to help me open up my tent,” she said, or offers to pick up a snack for her if they’re doing a lunch run.

“When I can set up next to a dear friend that I met through past fairs or Instagram, that’s the best,” Tallberg said. “So many of us are parents of little ones, and I love seeing the kids grow up together, in a sense, when their parents work the markets together. Or because I sell dolls, I often see the families that have bought dolls for their loved ones in the past, and the markets are a great way to meet in person.”

Nina Devenney of Wild Rosie. Courtesy Nina DevenneyWith an education in art and a creatively passionate family, Nina Devenney said she had always seen herself having a career in the arts. But she hadn’t envisioned a path that would lead to a family screen-printing business, Wild Rosie Designs, that now employs her husband as well.

Nina Devenney of Wild Rosie. Courtesy Nina DevenneyWith an education in art and a creatively passionate family, Nina Devenney said she had always seen herself having a career in the arts. But she hadn’t envisioned a path that would lead to a family screen-printing business, Wild Rosie Designs, that now employs her husband as well.

“While I had worked towards building a life as a full-time artist for about a decade after graduating from art school, the final change came swiftly and suddenly in the midst of the pandemic,” Devenney said. She was 10 weeks pregnant when the world locked down. “It was a vastly tender time, being pregnant for the very first time in a world that had gone silent with isolation,” she recalled.

“I realized I was going full-time about three months before my kiddo was born, and I leaned all the way in. My art became a haven; a safe place for a new mother in a world turned upside down. After my son was born, I literally could not control the ideas—they were like river rapids—one after the other and sometimes relentless in the most beautiful way. It was like I was being given this saving grace. My art held my hand through the hardest time of my life, and I held on back,” she added.

A selection of Wild Rosie's richly-colored, naturally dyed, hand-printed towels. This page: Courtesy Nina Devenney “I knew I needed to find a way to contribute financially to my family while trying to protect my vulnerable newborn in a threatening time. If I stayed home, protected him, and kept on making, I could keep him safe and fed,” she said. “That’s what I did. Patrick left his full-time job in 2021 to join me and here we are; a family of three with a thriving business that just expanded to include a traveling craft school that offers art workshops around the state of Maine, with hopes to expand beyond. It’s been one wild ride and we’re all in. Let’s see where this thing goes.”

A selection of Wild Rosie's richly-colored, naturally dyed, hand-printed towels. This page: Courtesy Nina Devenney “I knew I needed to find a way to contribute financially to my family while trying to protect my vulnerable newborn in a threatening time. If I stayed home, protected him, and kept on making, I could keep him safe and fed,” she said. “That’s what I did. Patrick left his full-time job in 2021 to join me and here we are; a family of three with a thriving business that just expanded to include a traveling craft school that offers art workshops around the state of Maine, with hopes to expand beyond. It’s been one wild ride and we’re all in. Let’s see where this thing goes.”

For Lauren Beveridge, 37, owner of Scout + Bean, the maker life and shows fall somewhere between a lifelong dream and and inevitable die that had been cast from the moment she was born. Scout + Bean is a one-woman show, where Beveridge creates a myriad of striking home goods from Maine-made rope—from baskets and trays to gathering mats and small goods—from her home studio in Lincolnville, Maine.

“My college degree is in psychology which has very little to do with sewing, but I’ve always known that I am happiest when I am making things. It wasn’t a surprise to me, or anyone in my life, that I chose to make a living as a creative,” Beveridge said.

Like Devenney, she said the pandemic played a role in her decision to make the proverbial leap into making her company her occupation and way of life.

“Scout + Bean is my full-time pursuit. When COVID hit, my husband and I decided that it made the most sense for him to take a break with work to become a full-time caretaker for our young daughter. That allowed me the freedom and time to really push my boundaries and see how many baskets and bowls I could sew, and how big I could grow this business,” she said.

For many of the artisans I spoke with for this story, making the commitment to full-time maker life coincided with an increase in shows and events, including the Common Ground Country Fair.

Mary and Joe Devenney. Courtesy Mary & Joe DevenneyNina Devenney’s parents, Joe and Mary Devenney, have a home pottery studio in Jefferson. While they have not exhibited at the Common Ground Fair since 2019, it’s where things got started for them after they moved to Maine in 1976.

Mary and Joe Devenney. Courtesy Mary & Joe DevenneyNina Devenney’s parents, Joe and Mary Devenney, have a home pottery studio in Jefferson. While they have not exhibited at the Common Ground Fair since 2019, it’s where things got started for them after they moved to Maine in 1976.

The senior Devenneys said they made the decision to hang up their so-called traveling show and move their focus in the direction of consignment sales. Yet like many others, the Devenneys were quick to explain the significant role of the fair in the evolution of their business.

“We picked up a lot of wholesale accounts over the years at the fair,” the couple said, adding, “That’s a real privilege: To be able to say ‘we’ll make [the pots] and you can pick them up.’”

But making it year-round is not always easy as a maker, and despite the common and deeply evident joy and passion woven through each story, there is also an element present of perpetual uncertainty.

The Devenneys said that they began to work on finding a financial balance as full-time makers decades ago.

The Devenneys said that they began to work on finding a financial balance as full-time makers decades ago.

“You learn early on to be frugal and do as much work as you can. January, April, May are pretty weak. Consignment shops are open but go into hibernation,” Joe said. When Maine shows were out of season, the couple traveled to other states, including Pennsylvania and Virginia. They learned that to make it as craftspeople, it is imperative to create diverse revenue streams.

Daughter Nina said she and Patrick rough out their creative and revenue plans annually—a process that is constantly evolving as their 5-year-old business grows.

“Thankfully the larger shows respond in the winter months whether we have been accepted or not,” Nina said of the juried entry requirements for some events. “We then look at our calendar and try to space out fairs around bigger shows like Common Ground so that we have time to create the inventory to fill our booth. We then look at what we need for our daily inventory as well as all the Maine and New Hampshire-based stores that carry our work. We just adore the shops, galleries, and general stores who’ve supported us. It always gets done, and just means that sometimes we have longer days and get less sleep than others.”

Scout + Bean’s Beveridge reported similar challenges. “It never feels like I can sew enough for the fair, but I always try my best to fill a UHaul!”

For some makers like the senior Devenneys, having a reliable and consistent demand for consignment fits the bill. While for Nina and Patrick, incorporating workshops and teaching opportunities for the public has been a recent and highly popular offering.

“There are definitely times of plenty as well as lean times throughout the year,” Nina said. “The longer we do this work the easier it is to weather the challenging times, even if it’s as simple as remembering, say, that we made it through May last year, there is a light at the end. This year we added teaching workshops to the Wild Rosie umbrella and have been blown away by the positive response. It has been a great way to boost our sustainability both financially and socially.”

For Beveridge, web sales and retailers that stock her craft products are consistent sources of year-round revenue. In fact, her list of hopeful retailers clamoring to line their shelves with her diverse, creative wares has grown to an impressive five pages. And no one in this crowd sees the demand for Maine-made artisan goods slowing down anytime soon.

The Linnea Co.’s Tallberg said, “I see the maker-made goods market growing 100 percent. Sustainability, eco-friendly and eco-conscious, environmentally conscious, recycling, repurposing, made in Maine, made in the U.S., artisan-made, practicing a craft, parent-entrepreneurs, supporting local business, maker-owned small businesses—that’s the future that I believe in.”

✮

Jenna Lookner is a reporter and special sections editor at Penobscot Bay Press. She grew up on a farm in Camden, and now lives in Little Deer Isle with her husband, their four dogs, heritage breed chickens, and geese.

About the Common Ground Country Fair

The Common Ground Country Fair has offered a well-curated and remarkably popular annual event each September for nearly 50 years. It is run by the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association.

The 2024 Common Ground Country Fair takes place September 20, 21 and 22, 2024, at the Common Ground Education Center in Unity, Maine. The fairgrounds are open Friday and Saturday 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. and Sunday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Fair tickets go on sale August 1, 2024 and can be purchased through mofga.org; additional programs and opportunities can also be viewed on the MOFGA website.