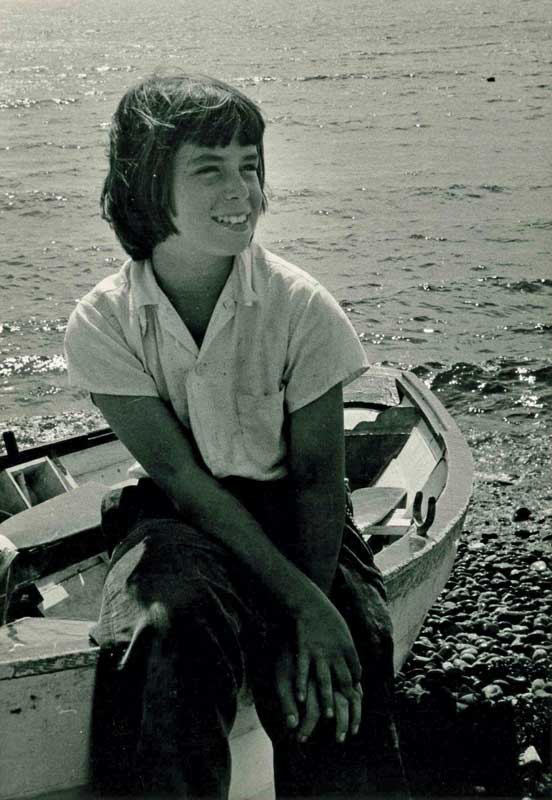

Abigail McEnroe, age 11, seated on her beloved dory. Image courtesy Abby McEnroe

Abigail McEnroe, age 11, seated on her beloved dory. Image courtesy Abby McEnroe

Rowing and dories are an important part of my life in Belfast, Maine, where I live and launched a business, DoryWoman Rowing. Having an on-the-water business, I have found that people reach out to me to share their own rowing stories, particularly women. One in particular, Abigail McEnroe, shared a tale that captivated me like no other.

During my first year in business, Abby, as I came to know her, emailed a black-and-white photo of the historic granite house she lived in on Mosquito Island, near Port Clyde. She said that she fished for lobster from her dory. I, of course, wanted to know more, so on a sunny mid-November afternoon I spoke with her by video conference, she in upstate New York and me from home.

When we connected, I was greeted by a friendly, rosy-cheeked woman in her late 70s. She was in her dining room, where an impressive antique glass bottle collection sat on a shelf behind her. The burnished afternoon sun shone through the glass, creating a warm, radiant glow in the room. Just like her smile.

Visits to the island during the Christmas season meant a snowy launch of the McEnroe dory. Image courtesy Abby McEnroeAbby grew up in Duchess County, in upstate New York. Her parents, Frank and Janet, were teachers at a private school there. In the summer, Frank worked for the Audubon Society, leading educational outings in midcoast Maine. On one summer expedition, as they motored by Mosquito Island, near Martinsville and Tenants Harbor, Frank was told that the island, a former granite quarry a mile or so off the mainland, was for sale for $2,000, and that he should buy it. He did. It was 1940.

Visits to the island during the Christmas season meant a snowy launch of the McEnroe dory. Image courtesy Abby McEnroeAbby grew up in Duchess County, in upstate New York. Her parents, Frank and Janet, were teachers at a private school there. In the summer, Frank worked for the Audubon Society, leading educational outings in midcoast Maine. On one summer expedition, as they motored by Mosquito Island, near Martinsville and Tenants Harbor, Frank was told that the island, a former granite quarry a mile or so off the mainland, was for sale for $2,000, and that he should buy it. He did. It was 1940.

Each May, after school got out, Abby and her family arrived in Martinsville to embark to their island, but they needed a way to get to there. A local fisherman, Clarence Dwyer, took them under his wing and lent them his dory for their immediate transportation needs. Then he connected them to a boatbuilder in Friendship, who built them their own dory: 17 feet long and “really graceful,” as she described it. “Really balanced and bowed out in the middle. We paid either $75 or $125 for it.” The family got another rowboat in the 1950s but in her opinion, “It was never as graceful as the first dory.”

The boat was used to transport the McEnroe family and everything they needed to live on the island for the summer. This included Abby, her parents, and her two older brothers, Dorn and Michael, as well as vast stores of canned food, building supplies, and animals. Frank had started a zoo at the school where he taught, and would bring home “pets” that would join the family on the island. The menagerie included raccoons, rabbits, sparrow hawks, dogs, and, on one occasion, a donkey! A donkey in a dory is an image you just can’t get out of your mind.

Abby sanding her dory on a hot island summer day. Image courtesy Abby McEnroeEach summer, when the family arrived in Maine, they would head to the Dwyer’s property, where they stored their boat upside down. They would flip it upright and roll it down the beach to the water’s edge on logs, a traditional way of launching a boat. Then they’d row a mile over to their island’s rock beach, unload the boat, and tie it to a small-but-sturdy fish house.

Abby sanding her dory on a hot island summer day. Image courtesy Abby McEnroeEach summer, when the family arrived in Maine, they would head to the Dwyer’s property, where they stored their boat upside down. They would flip it upright and roll it down the beach to the water’s edge on logs, a traditional way of launching a boat. Then they’d row a mile over to their island’s rock beach, unload the boat, and tie it to a small-but-sturdy fish house.

The family’s stone house likely dated back to the late 1700s. The Cape is built of granite from the island, using a technique not commonly in use after 1750. In a photo from the time of the family’s ownership, the house looks mythic, indestructible, a Maine-style fortress. Abby said the family repaired it for the next 50 years. There were several outbuildings on the property: a barn, a cabin for guests, and outhouses. There was a well for water that pumped indoors, a kerosene refrigerator, and a stove. Eventually, they brought a generator to the island to power appliances such as wool shears.

A herd of sheep inhabited the island, having been there since the 1800s. It was commonplace then to keep livestock on Maine islands—hence, the many with names such as Ram, Sheep, or Cow. No fences were needed and there were no predators. (A modern-day version of this practice is captured in an iconic image by photographer Peter Ralston of a large workboat towing a sheep-filled dory. The sheep were being transported to populate Allen Island, located not far from Mosquito Island.)

Abby spoke of what sounded like an idyllic childhood. A life characterized by deep communion with nature, intense freedom, synchronicity with weather and tides, and a lot of hard work.

Newlyweds Abby and Jim arrive on Mosquito Island, greeted by Abby’s mom, Janet. It was Jim’s first visit to the island. Image courtesy Abby McEnroeWhen they weren’t doing chores, she and her brothers had the entire 200 acres to range and rove over. And they had their dory, a boat that was central to her memories. She and her brothers used it for fishing, adventuring, and play. She would sometimes fish by herself, wearing tall wader/hip boots folded over with buckles that clanked. “The dangerous part,” she said, “was if you fell overboard, they would fill with water and sink you right to the bottom.” Abby had a close call once, never to happen again.

Newlyweds Abby and Jim arrive on Mosquito Island, greeted by Abby’s mom, Janet. It was Jim’s first visit to the island. Image courtesy Abby McEnroeWhen they weren’t doing chores, she and her brothers had the entire 200 acres to range and rove over. And they had their dory, a boat that was central to her memories. She and her brothers used it for fishing, adventuring, and play. She would sometimes fish by herself, wearing tall wader/hip boots folded over with buckles that clanked. “The dangerous part,” she said, “was if you fell overboard, they would fill with water and sink you right to the bottom.” Abby had a close call once, never to happen again.

With amusement, she described how she and her brothers once tried to sink the dory and were unsuccessful. The boat filled up to the “gunny rails” with water but remained afloat. They had to wait for the tide to go out so they could stand on the beach and bail it out. Abby said that this experience proved to her “that it was a good, sturdy boat.”

The family's granite house on Mosquito Island is thought to have been built in the 1700s. Image courtesy Abby McEnroe.

The family's granite house on Mosquito Island is thought to have been built in the 1700s. Image courtesy Abby McEnroe.

For at least some of their tenure on the island, the family powered the dory by oars. Later, they added a second dory to their fleet, cutting out a keyhole opening in the its stern and mounting a 5-hp engine. If they were hauling heavy goods or building materials, they would use both boats, side-by-side, one fitted with an outboard, like a kind of catamaran. Supplies were piled and balanced between the two boats. They even moved big barrels in the dories.

They used them to transport wool sheared from the sheep back to the mainland to sell to the Knox Woolen Mills in Camden, and also moved a surplus of lambs off the island, tying the animals to the gunny rails, so they didn’t go anywhere.

“They were workboats,” Abby said. “We weren’t nice to them.”

Once on the island, the family remained until it was time to head back to New York. They ate a lot of canned goods, augmented by fresh vegetables. Her mother, Janet, was a horticulturist and cultivated a garden that supplied the family with a bounty of produce.

The author, Nicolle Littrell, sharing her love of rowing with others on a summer evening. Photo by Elizabeth BeallIsland time wasn’t restricted just to the summer. In December, they would make the long drive to Maine from upstate New York for the holiday break, and celebrate Christmas on the island. They would follow the same protocol as in summer: unwrapping the dory like a present, flipping it over, and rolling her down the snowy beach to launch.

The author, Nicolle Littrell, sharing her love of rowing with others on a summer evening. Photo by Elizabeth BeallIsland time wasn’t restricted just to the summer. In December, they would make the long drive to Maine from upstate New York for the holiday break, and celebrate Christmas on the island. They would follow the same protocol as in summer: unwrapping the dory like a present, flipping it over, and rolling her down the snowy beach to launch.

One of my favorite photos that Abby shared was of her sitting on the side of her dory. She was 11 or 12, and radiated vitality and confidence. Another showed her as a young woman, sanding her dory in cut-offs and a bra. She explained, “We didn’t always wear a lot of clothes on the island … but it probably was a hot day, and I had a lot of sanding to do.”

There was also a picture of her and her husband, Jim, on his first visit to the island. He was a handsome man in a collegiate jersey flanking one side of a small boat, Abby on the other, both all smiles. There was a dory moored in the background. And there was a story there. It was their honeymoon, and Abby’s folks, Frank and Janet, didn’t know they were going to visit. It was a clear night, and Clarence Dwyer had lent them a rowboat. Jim started rowing, but Abby wasn’t impressed with her new husband’s skills. Like many novice rowers, he favored one side over the other, resulting in the boat going in a circle.

A present day portrait of Abigail “Abby” McEnroe. Photo by Nicolle LittrellGiven that Jim was a professional baseball player, Abby didn’t want to offend him by giving him pointers. Meanwhile, Frank, spying them from shore said, “Here’s the new couple” and went out in the dory with the outboard and towed them in. Abby and Jim have been married for almost 60 years.

A present day portrait of Abigail “Abby” McEnroe. Photo by Nicolle LittrellGiven that Jim was a professional baseball player, Abby didn’t want to offend him by giving him pointers. Meanwhile, Frank, spying them from shore said, “Here’s the new couple” and went out in the dory with the outboard and towed them in. Abby and Jim have been married for almost 60 years.

When her parents died, she and her brothers kept the homestead for a spell, however, the mounting cost of maintaining an island on the coast of Maine and a historic granite house took a toll. “Taxes finally got us,” she said, and they sold it in 1987, having owned it for 47 years. By then, Abby, Jim, and their two children were settled on a dairy farm, not far from Cooperstown, New York.

I’ve heard other moving dory stories from women who, like Abby, rowed when they were growing up, creating for me a lineage of dorywomen through the ages. I’d like to think I’m keeping a slice of that tradition alive whenever I go for a row in my dory.

✮

Nicolle Littrell (photo above) is a licensed Maine Guide, filmmaker, photographer, and founder of DoryWoman Rowing. Learn more at dorywomanrowing.com or on Instagram and Facebook @dorywomanrowing.