Photos by Benjamin Mendlowitz

The 28-foot ketch Swallow was featured in the L. Francis Herreshoff series, The Compleat Cruiser, published in The Rudder magazine in the mid-1950s.

The 28-foot ketch Swallow was featured in the L. Francis Herreshoff series, The Compleat Cruiser, published in The Rudder magazine in the mid-1950s.

When a number of us classic boat types in Brooklin, Maine, decided to launch the video website, offcenterharbor.com, we took as our mission statement a quote from iconic yacht designer and writer,

L. Francis Herreshoff: “Simplicity afloat is the surest guarantee of happiness.”

To say that the quotation has served us well over the years would be an understatement. At offcenterharbor.com we want to show how the design, construction, and use of boats can be fun and interesting; a lifelong and multi-generational pursuit with the power to anchor families on the natural world of the sea and, on a weekly basis, instruct them on the virtues of minimalism.

So, who is this patron saint of ours who spoke out against encrusting boats with nautical claptrap and complex machinery of dubious reliability and thought a cedar bucket could be pretty much sufficient as far as maritime plumbing was concerned? And even more to the point, who is this man whose yacht designs and writings reach out so vividly more than three-quarters of a century after they were put down on paper?

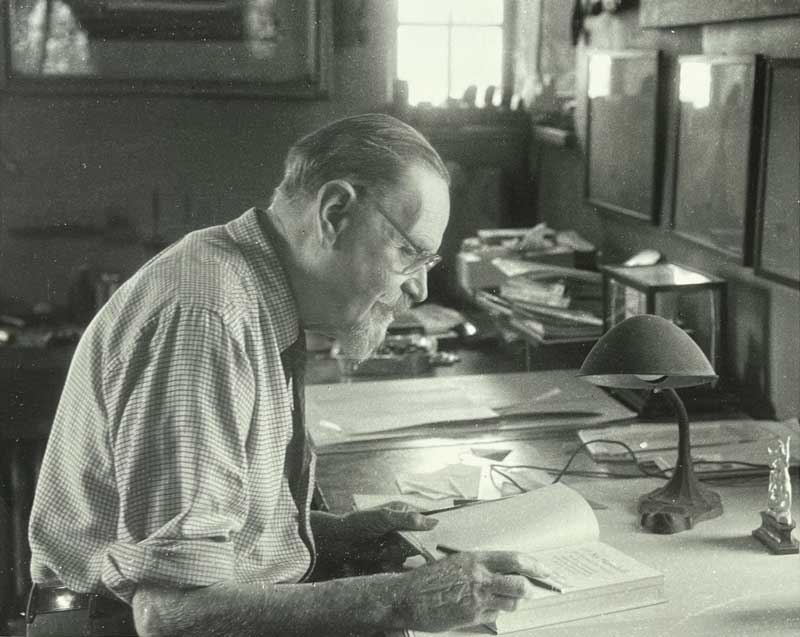

L. Francis Herreshoff worked for many years from his castle overlooking the harbor in Marblehead, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy Marblehead Historical Commission

L. Francis Herreshoff worked for many years from his castle overlooking the harbor in Marblehead, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy Marblehead Historical Commission

Virginia is an Araminta replica and 43 feet long. Like many of Herreshoff’s favorite designs, she’s ketch rigged.In my mind, the story of L. Francis Herreshoff began when he was a little boy, and his father, the great Nathanael Greene Herreshoff, sent him over to observe the goings on at the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. in Bristol, Rhode Island, after telling the men at the yard to look out for the kid. From that day forward, L. Francis, a keen observer of all things mechanical and structural, absorbed the day-to-day work of one of the great shipyards in American history as it went about building vessels both large and small out of wood, steel, and even bronze.

Virginia is an Araminta replica and 43 feet long. Like many of Herreshoff’s favorite designs, she’s ketch rigged.In my mind, the story of L. Francis Herreshoff began when he was a little boy, and his father, the great Nathanael Greene Herreshoff, sent him over to observe the goings on at the Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. in Bristol, Rhode Island, after telling the men at the yard to look out for the kid. From that day forward, L. Francis, a keen observer of all things mechanical and structural, absorbed the day-to-day work of one of the great shipyards in American history as it went about building vessels both large and small out of wood, steel, and even bronze.

Although he was a whiz at understanding machinery and had a keen eye for line and form, L. Francis was what educators would now describe as a dyslexic and consequently had such trouble in the classroom that he was forced to repeat several grades before he could get out of grammar school. Instead of attending the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, like his older siblings, he was sent to the state agricultural college and then assigned by his father the task of running the family’s dairy farm on the other side of town. Luckily, a successful tour as a naval officer followed by an apprenticeship with the yacht designer Starling Burgess led him back into the world of yachts in his mid-20s; a fortuitous moment at which his native talent as a designer came to the front. Hardened by school troubles and a stint shoveling cow manure at the farm, L. Francis strode into adulthood, a man determined to make his way his own way.

Brigadoon, ex Joann, was built by Britt Brothers of West Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1924, and was the first of Herreshoff's clipper-bow yachts. Bought by Sterling Hayden, she was shipped to California, where she has been an icon on San Francisco Bay ever since.

Brigadoon, ex Joann, was built by Britt Brothers of West Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1924, and was the first of Herreshoff's clipper-bow yachts. Bought by Sterling Hayden, she was shipped to California, where she has been an icon on San Francisco Bay ever since.

Those of us in awe of his genius begin by appreciating his artistic abilities and inclinations. Or as he put it, “Drawing these curves of endless variation calls for special skills, and it is these curves that to a great extent put naval architecture and yacht design more in the realm of art than cold science.”

In another respect, where his father had to churn out sufficient work to keep several hundred Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. boatbuilders profitably engaged, L. Francis had the luxury of following his dreams, first at Burgess, Swasey, and Paine, and then in Marblehead where he spent the second half of his life living and working in a picturesque and commodious stone castle overlooking the harbor.

Thanks to a group of loyal and well-heeled admirers who sought out his designs and were willing to put up with a personal style that could only be described as eccentric, Herreshoff was free to design one beautiful boat after the other. And when there was no specific patron, as a Yankee bachelor living close to the bone economically, he could draw boats springing directly out of his own abundant imaginings. For the lover of classic boats, these drawings are magical.

The 28-foot Ben My Chree was built in 1933 for Willoughby Stuart, and spent much of her life on the Maine Coast. She was restored in 2013 at Ballentine’s Boat Shop in Cataumet, Massachusetts.

The 28-foot Ben My Chree was built in 1933 for Willoughby Stuart, and spent much of her life on the Maine Coast. She was restored in 2013 at Ballentine’s Boat Shop in Cataumet, Massachusetts.

They are also especially detailed. Writing in his book, Sensible Cruising Designs, Herreshoff said, “The cost of modern yachts seems to be 15 times greater than those built before World War I, while the cost of real estate, clothes and food is only about three times greater. Much of the increase in modern yacht costs come from complications and changes in design where details are not properly drawn out for workmen.”

Without “Skipper” Herreshoff’s notable experience as a sailor, it is doubtful that either his boat designs or

later his writings in the magazine, The Rudder, could remain as authoritative and beguiling as they remain today. As a boy he had often cruised with his older brothers on the waters of Narragansett Bay as well as in the small boats carried on the deck of his father’s steam yacht during family sojourns along the New England Coast.

In 1942, already established as a preeminent American designer, Herreshoff was approached by the editor of The Rudder, Boris Lauren-Leonardi, to write about the sailing and building of small boats. It was the height of World War II and one can only imagine the impact his writings had on G.I.s as he spun out tales of small voyages around Boston’s North Shore and Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard in The Compleat Cruiser.

Sprite is a fine example of L. Francis Herreshoff’s “Rozinante,” which he described as a canoe yawl design.

Sprite is a fine example of L. Francis Herreshoff’s “Rozinante,” which he described as a canoe yawl design.

Imagine how eagerly they awaited his designs and instructions about how they could build one snug little craft or another in the garage or out in the backyard when they were finally discharged back into civilian life. Enmeshed in the terrors of the war, an imaginary voyage spun out in the pages of The Rudder in 1943, with Goddard and Weldon in command of the ketch Viator and the Rozinante. It brought not only a sense of calm and certitude, it pointed to a future in which men of experience and good sense would have total control.

Although in his lifetime he had designed especially beautiful large yachts such as the 12 meter Whirlwind, the 71-foot Landfall, Tioga, Bounty, the 73-footer Ticonderoga, and many others, it was smaller boats like the Rozinante, Ben-My-Chree (“My Darling Girl” in Gaelic), Quiet Tune, and Araminta that won the hearts of The Rudder readers so long ago and keep winning our hearts today.

✮

Bill Mayher lives in Brooklin, Maine, and is one of the founders of offcenterharbor.com.