With changing weather patterns and warming temperatures catalyzing the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to update the growing zones for the first time in nearly half the country, Maine farmers are facing changing times head on. That includes shifting winter maintenance and spring preparation to optimize the success of their growing season.

A recent survey of three midcoast area operations revealed ways in which Maine farmers there are adapting.

Dooryard Dahlias, the newest addition to the crops grown at Camden’s Dooryard Farm. Photo courtesy Dooryard Farm

Dooryard Dahlias, the newest addition to the crops grown at Camden’s Dooryard Farm. Photo courtesy Dooryard Farm

Digging for Dahlias

Marina Sideris with the bounty of her labor. Photo courtesy Dooryard Farm At Camden’s Dooryard Farm, Cooper Funk and Marina Sideris have been producing a diverse bounty of organic produce since 2012. In 2023, the farm expanded to include a robust dahlia program inherited from a nearby farm, and Dooryard Dahlias was born.

Marina Sideris with the bounty of her labor. Photo courtesy Dooryard Farm At Camden’s Dooryard Farm, Cooper Funk and Marina Sideris have been producing a diverse bounty of organic produce since 2012. In 2023, the farm expanded to include a robust dahlia program inherited from a nearby farm, and Dooryard Dahlias was born.

The couple explained that in the fall, the dahlia tubers are dug up and saved to sell and to replant the following spring; in 2023 they dug approximately 20,000 plants.

“There’s a little bit of bed prep to be done in the spring, but it’s mostly about getting [the dahlias] in the ground and maintaining conditions until they are mature enough to fend for themselves. It takes two to three weeks to get them all planted,” Funk said.

Dahlias are not frost tolerant, Sideris added, so the timing of their planting is crucial.

Funk and Sideris are no strangers to challenging weather, having farmed in California’s Sierra foothills, with the risk of wildfires looming large at times. Funk said at Dooryard Farm an increasing shift to no-till beds has been a sound goal for the Maine Organic Farmers Association (MOFGA)-certified farm.

“We’re noticing ‘seasonal slippage,’” Sideris explained. The seasons have been longer and warmer.

“Our biggest challenge in the spring is extreme weather events, erosion being the biggest issue. Unprotected soil is at significant risk during 5-inch rain events,” Funk said, adding that the rainy spring and early summer in 2023 were difficult. “There are so many aspects of the climate that are impactful, largely wind.”

At Dooryard, the couple utilizes 3 of their 40-plus acres to grow. They have two high tunnels and a greenhouse as well as a half-acre of dahlias.

Marina Sideris waters seedlings in a greenhouse at Dooryard Farm in Camden. Photo courtesy Dooryard Farm Funk explained that no-till beds are hand-planted and do not require the use of a tractor for preparation. With muddy spring terrain creating an increasing challenge for machinery, the no-till method allows planting to begin when the ground and farm are ready—a timeframe that lends itself to earlier planting and listening to the environment, not working at the mercy of Maine’s infamous mud season.

Marina Sideris waters seedlings in a greenhouse at Dooryard Farm in Camden. Photo courtesy Dooryard Farm Funk explained that no-till beds are hand-planted and do not require the use of a tractor for preparation. With muddy spring terrain creating an increasing challenge for machinery, the no-till method allows planting to begin when the ground and farm are ready—a timeframe that lends itself to earlier planting and listening to the environment, not working at the mercy of Maine’s infamous mud season.

Speaking of 2023, Funk explained that some of their crops could not be planted until July due to persistent June rains and the resulting mud.

However, ultimately the season turned out well.

The work horses at Horsepower Farm do chores usually reserved for machines on most farms these days. Photo courtesy Horsepower FarmBlue Hill’s for Horses

The work horses at Horsepower Farm do chores usually reserved for machines on most farms these days. Photo courtesy Horsepower FarmBlue Hill’s for Horses

At the fourth-generation Horsepower Farm in Penobscot in the Blue Hill region, Andrew and Meghan Birdsall are continuing the tradition of using Suffolk Punch draft horses to perform many of the tasks that modern farms rely on machinery to do. The Suffolk Punch is a unique breed—and a rare one. With a scarce number hovering around 1,000 remaining worldwide, they are listed as “Critical” by The Livestock Conservancy.

“Horsepower Farm is unique because of our use of the Suffolk Punch draft horse which is a critically endangered breed. Farm work using draft-horse power is unique on its own but rare-breed preservation is even more so,” Andrew Birdsall said. “I also think the generational aspect of our farm adds a unique quality to the place. My close relationship with my grandfather, Paul, was special. I feel connected to him by carrying on his work here.” At Horsepower Farm in Penobscot, the Birdsall family works with Suffolk Punch draft horses. Photo courtesy Horsepower FarmMy grandparents, Paul and Mollie, moved [to the Blue Hill Farm] in the 1970s during the “back to the land” movement. My grandfather was especially concerned with land conservation. My parents took over after them, and now my wife and I are running the farm. Our children make the fourth generation here,” Andrew Birdsall said.

At Horsepower Farm in Penobscot, the Birdsall family works with Suffolk Punch draft horses. Photo courtesy Horsepower FarmMy grandparents, Paul and Mollie, moved [to the Blue Hill Farm] in the 1970s during the “back to the land” movement. My grandfather was especially concerned with land conservation. My parents took over after them, and now my wife and I are running the farm. Our children make the fourth generation here,” Andrew Birdsall said.

“Putting the farm to bed” for the winter involves harvesting storage crops, including potatoes, carrots, beets, onions, and garlic. Other winter chores involve submitting soil samples for testing and field planning to determine which crops will thrive in various areas of the farm; repairing fences and structures; moving sheep back to their “home” barn to over-winter; and perhaps the biggest task: ordering seeds.

The Birdsall’s children are the fourth generation to work the land in Penobscot. Photo courtesy Horsepower Farm

The Birdsall’s children are the fourth generation to work the land in Penobscot. Photo courtesy Horsepower Farm

“It’s quite a big undertaking! There are many questions to think about when we put together a seed order: What do we want to grow next season? How much? Who are we selling these crops to?” Andrew Birdsall explained.

Abundant healthy lavender is a feast for the senses at Glendarragh Farm. Photo courtesy Glendarragh FarmLaboring for Lavender

Abundant healthy lavender is a feast for the senses at Glendarragh Farm. Photo courtesy Glendarragh FarmLaboring for Lavender

At Glendarragh Farm in Appleton, Lorie Costigan and her family have been growing numerous varieties of lavender since 2007. Costigan said that while spring preparation is important when the time arrives, winters are largely about maintenance, planning, and the production of their line of value-added lavender products, sold both online and at their brick-and-mortar shop, open year-round on Camden’s main street.

Costigan prepares for winter by meticulously covering the thousands of plants at Glendarragh with gauzy white fabric to protect them from the elements. She said a significant portion of the winter is spent curing and sifting lavender and producing the salves, soaps, creams, sachets, and more that Glendarragh customers return for year after year. She works with local makers to create many of her signature items, and said the winter is a time to connect with that side of her business. She also spends days outdoors scouting areas of the farm for new beds and planning for the season.

“Although lavender is a perennial that blooms and is harvested in July, August, and again in October, we store it through the winter and continue sifting through it. It’s a great project to be able to do during the winter,” Costigan said, explaining that they get two harvests of the flowers each season. “Lavender season is summer, but lavender farmers are busy year-round.”

Lorie Costigan plants a variety of lavenders, which get harvested and turned into products. Photo courtesy Glendarragh FarmFor sachets, Costigan said that Glendarragh uses the Dutch varieties of lavender grown on the farm. For culinary lavender, the English varieties are preferred. Lavender plants can thrive in production for at least two decades, Costigan explained.

Lorie Costigan plants a variety of lavenders, which get harvested and turned into products. Photo courtesy Glendarragh FarmFor sachets, Costigan said that Glendarragh uses the Dutch varieties of lavender grown on the farm. For culinary lavender, the English varieties are preferred. Lavender plants can thrive in production for at least two decades, Costigan explained.

After the protective fabric was torn from the beds in a pre-Christmas windstorm, Costigan vowed to replace it, but speculated that such measures may not be necessary during future winters.

“It’s increasingly been earlier and earlier that we can remove the protection fabric. In recent winters it has been as early as March,” she said.

She explained that she walks the rolling rows of meticulously covered plants religiously, peeking beneath the covers to inspect the plants for health and the first signs that they are ready to greet the spring.

Costigan said lavender typically breaks its dormancy, “when the humidity returns to the air.” She looks for signs that the foliage is growing and greening, all signs that the growing season is beginning.

“As soon as the ground is ready to be worked, we will add more beds,” Costigan said.

Lavender cures in the barn at Glendarragh Farm. Photo courtesy Glendarragh FarmAdditionally, Costigan does landscape consulting for clients with gardens of various sizes wishing to grow their own lavender.

Lavender cures in the barn at Glendarragh Farm. Photo courtesy Glendarragh FarmAdditionally, Costigan does landscape consulting for clients with gardens of various sizes wishing to grow their own lavender.

“Lavender doesn’t require a great deal of maintenance—it’s green by Memorial Day and we cut it back in October,” she said.

Sure Signs of Spring

At Horsepower Farm, spring priorities include starting seedlings, preparing greenhouses for planting, delivering lambs, and hiring summer workers.

“We start a lot of our seeds in our house. Watching the young plants grow and the smell of the soil are among our favorite parts of spring. Lambing season, too, is an exciting part of spring. It usually lasts about one month and keeps us quite busy—checking on ewes and making sure newborn lambs are getting a healthy start. Planting the rest of the crops—root vegetables and everything that is started directly in the ground, rather than as seedlings—is the other big goal each spring. Making rows in the market garden, spreading compost, planting, and setting up irrigation are all things that have to be done,” Andrew Birdsall said.

Birdsall added that he looks forward to continuing to build the draft-power program in 2024.

Dooryard Farm, too, has big plans for the upcoming year: they are in the process of building a larger farm stand and market that will provide both convenient parking and easy access to the dahlia fields, which are a popular attraction.

Costigan opens Glendarragh Farm to the public seasonally on a limited schedule, and the sprawling fields of purple lavender have become an iconic photo location and an agricultural tourism destination as well.

“It’s purposeful work, seven days a week, and it keeps me grounded and connected to the land and the seasons,” Costigan said.”

✮

Jenna Lookner is a writer and the Communications Director at Seal Cove Auto Museum. She grew up on a farm in Camden and lives in Little Deer Isle with her husband, their four dogs, heritage breed chickens, and geese.

Tracking a Shifting Climate

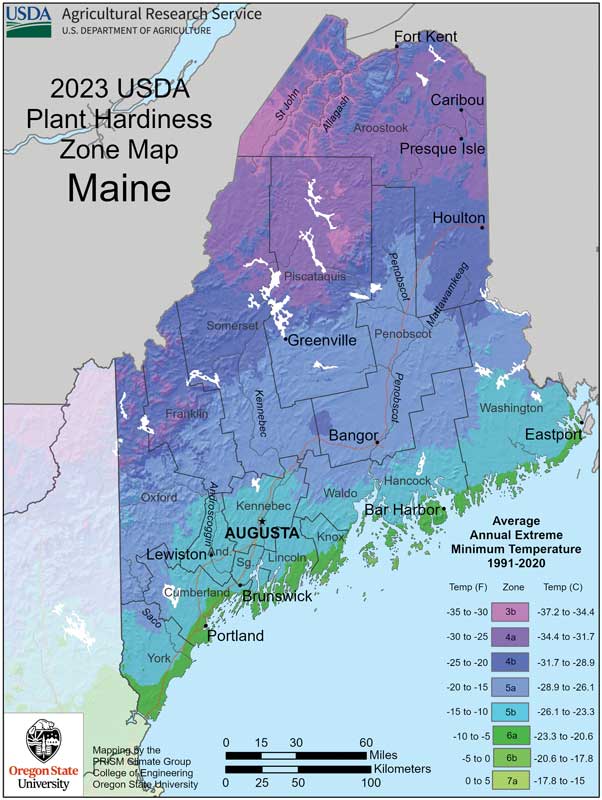

Courtesy U.S. Department of Agriculture

Courtesy U.S. Department of Agriculture

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Plant Hardiness Zone Map is a standard tool used by farmers and gardeners. This resource is designed as a guide to which plants are likely to thrive successfully in respective growing zones. The map is based on the average annual extreme minimum winter temperature, depicted on the map by colors assigned to 10-degree Fahrenheit zones and 5-degree Fahrenheit half zones, from minus 60 to 70 degrees F.

In the most recent map, 2023, coastal Maine was reassigned from Zone 5b to Zone 6a, a change of about 5 degrees to the warmer.

A link to the Plant Hardiness Map and additional resources is available at planthardiness.ars.usda.gov.

According to the Maine Climate Council, climate change is impacting Maine dramatically and at a swifter pace than in many other parts of the country. Sea level rise, erosion, increasing severe weather events, as well as warming water and air temperatures are but a few of the factors that will continue to impact Maine.

In 2020, Maine’s four-year climate action plan “Maine Won’t Wait” was unveiled. Progress reports and details about the “Maine Won’t Wait” plan are available at maine.gov/climateplan.

The USDA, too, has taken a broad interest in the impacts of a changing climate on farming and the economics of agribusiness.

“Annual precipitation since the beginning of the last century has increased across most of the northern and eastern United States and decreased across much of the southern and western United States. Changes in the seasonal distribution of precipitation are also projected; over the coming century, significant increases are projected in winter and spring over the Northern Great Plains, the Upper Midwest, and the Northeast,” states the USDA’s Economic Research Service, which is studying numerous climate-related factors impacting agriculture nationwide.

More information from the USDA Economic Research Center can be found at ers.usda.gov.