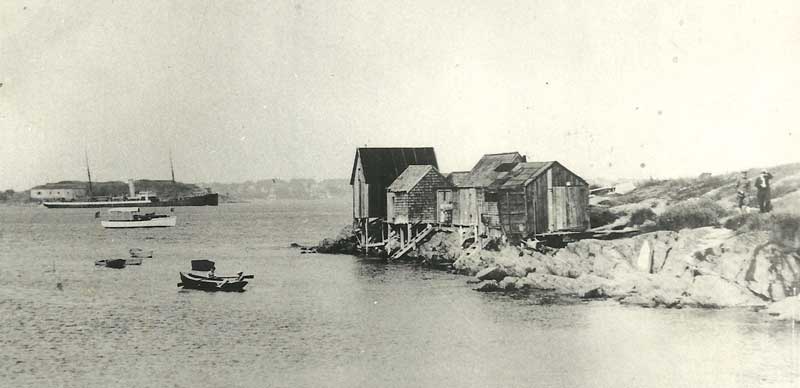

Fishing shacks in South Portland date back to the late 1800s, when fishing schooners and cargo ships anchored off Fisherman’s Point. Photo courtesy South Portland Historical SocietyFor some 140 years, simple fishing shacks on a jut in South Portland known as Fisherman’s Point were as much a part of the landscape as the rising sun—until that fateful day in January 2024 when a torrential storm and never-before-seen high tide washed them away and smashed them into smithereens.

Fishing shacks in South Portland date back to the late 1800s, when fishing schooners and cargo ships anchored off Fisherman’s Point. Photo courtesy South Portland Historical SocietyFor some 140 years, simple fishing shacks on a jut in South Portland known as Fisherman’s Point were as much a part of the landscape as the rising sun—until that fateful day in January 2024 when a torrential storm and never-before-seen high tide washed them away and smashed them into smithereens.

Within hours of their destruction, the fundraising had begun in hopes of rebuilding the structures so they can continue serving as living reminders of South Portland’s rich maritime history and connection to the sea. In the first week alone, people donated more than $10,500 to the South Portland Historical Society, said Kathryn DiPhilippo, a local historian and the organization’s executive director.

Why not replace them? she asked. The shacks gave the area a depth, a character, and a sense of history, and were the last remaining visible links to South Portland’s fishing industry.

“Why do you have to have those wash away and (permanently) feel that loss?” she said. “Why can’t the community pick itself up and put them back, because we have the plans and they’ll look exactly the same. Then, next summer or the summer after, people can go down to the beach, look at those shacks and have community pride, like ‘We did it! We rebuilt them and there they are.’”

Record high tides and wind-driven waves washed the popular fishing shacks into the harbor. Photo by Jack Bjorn PhotographyThe three fishing shacks that were destroyed January 13 were never grandiose or particularly awe-inspiring. They were modest unassuming wood structures—only 461 square feet among them—atop ordinary timber pilings on a rocky shoreline at the edge of South Portland’s Willard Beach.

Record high tides and wind-driven waves washed the popular fishing shacks into the harbor. Photo by Jack Bjorn PhotographyThe three fishing shacks that were destroyed January 13 were never grandiose or particularly awe-inspiring. They were modest unassuming wood structures—only 461 square feet among them—atop ordinary timber pilings on a rocky shoreline at the edge of South Portland’s Willard Beach.

But for all they lacked in pretentiousness, the fishing shacks were rich with history and a simple beauty that made them iconic to beachgoers, artists, photographers, history buffs, and boaters who passed by on the waters between the mainland and Casco Bay’s Cushing and House islands.

The shacks were visual reminders of generations and even centuries past when Simonton Cove was active with fishing and cargo schooners, fish-processing houses, and grizzled fishermen. The cove, a 4-acre inlet that stretches from Fisherman’s Point at the south end of Willard Beach to Southern Maine Community College at the north end, was settled about 300 years ago and was among the first commercial fishing communities in the Portland region.

The shacks hadn’t been used by fishermen in 40 years or so. But three of them, two of which were attached, still stood proudly within sight of better-known landmarks. From Fisherman’s Point, you can see historic Portland Head Light, the monstrous Civil War-era Fort Gorges in Portland Harbor, and Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse, located at the end of a 900-foot breakwater.

Scottish and Irish settlers arrived at Simonton Cove in 1718, where members of the Simonton family built a wharf and warehouse at what is now Fisherman’s Point.

The cove was home to fishing schooners and cargo vessels that brought things such as Maine fish and lumber to the West Indies before returning with sugar, molasses, and rum. Ramshackle shacks, where fishermen kept their gear, are thought to have first appeared along Willard Beach in the 1860s.

When some of the beachfront property was sold in the 1880s, most of the fishermen moved their fishing shacks from the beach to nearby Fisherman’s Point. One account said some of them simply dragged them along the beach to the rocky peninsula. And there they remained during times of transition when Willard Beach became a popular recreational destination with restaurants, dance halls, and hotels that came and went from the mid-1890s through the mid-1960s.

When the city bought Fisherman’s Point in 1907 and turned it into a park, the fishermen and their shacks were allowed to stay for a small fee paid to the city each year. At one time, there were possibly up to nine or ten shacks on the point, a number that dwindled to five after World War II. By then, they were used primarily by lobstermen to store buoys, rope, traps, oilskins, oars, and other gear.

A wicked storm wiped out two of the shacks in 1978, leaving only the three. For the most part, fishermen stopped using the shacks after that, but at least one kept at it. That lobsterman, Richard Holt, said he was the last fisherman to use the shacks, eventually leaving sometime in the mid-1980s; he’s not sure of the exact year.

Lobsterman Richard Holt has a number of mementos from the fishing shacks, including a wooden bilge pump. Photo by Clarke CanfieldHolt, 71, still lives in the same house he grew up in near Willard Beach. While reminiscing in his home, he pulled out albums of photos of the shacks, and a few of his drawings of them. He has postcards from the 1800s featuring photos of the shacks and the fishermen who used them.

Lobsterman Richard Holt has a number of mementos from the fishing shacks, including a wooden bilge pump. Photo by Clarke CanfieldHolt, 71, still lives in the same house he grew up in near Willard Beach. While reminiscing in his home, he pulled out albums of photos of the shacks, and a few of his drawings of them. He has postcards from the 1800s featuring photos of the shacks and the fishermen who used them.

Holt recalled venturing into a shack with friends as a teenager for some nighttime shenanigans, firing up a potbelly stove to keep warm. When he left his shack for good in the 1980s and moved his boat to Portland, he took some of the remaining things, including an old wooden manual bilge pump that fisherman used more than a century ago.

The shacks were refurbished multiple times after fishermen abandoned them in the 1980s, most recently last September when city workers repaired the shingle siding and asphalt roofs and put on a fresh coat of paint.

Holt is particularly proud of photos that show volunteers from the Willard Beach neighborhood repairing and rebuilding the shacks, first around 1991 and again in 1999. “It’s about our maritime heritage,” he said. “There’s a lot of history in those shacks.”

Before January’s storm, the shacks had been locked up for years, but were still an allure to dog-walkers, beach-goers, artists and photographers, and those who simply like to stroll down to Fisherman’s Point. When they were destroyed, videos and photos of them being washed out to sea circulated widely on the internet, and people mourned on social media as if they had a lost close friend. Their demise drew national media attention.

South Portland’s fishing shacks were a favored subject for artists such as Catherine Bickford. Photo by Clarke CanfieldCatherine Bickford, who lives in the Willard Beach neighborhood, has created dozens of paintings of the shacks, which tend to sell fast. Besides being a living memorial to the region’s maritime history, the shacks were an artist’s dream with their lines and angles, background scenery, and intense pinks, oranges, reds, blues, and other colors when the sun hit just right, she said.

South Portland’s fishing shacks were a favored subject for artists such as Catherine Bickford. Photo by Clarke CanfieldCatherine Bickford, who lives in the Willard Beach neighborhood, has created dozens of paintings of the shacks, which tend to sell fast. Besides being a living memorial to the region’s maritime history, the shacks were an artist’s dream with their lines and angles, background scenery, and intense pinks, oranges, reds, blues, and other colors when the sun hit just right, she said.

“It’s like a modern sculpture,” Bickford said. “It’s just a gorgeous receptacle for our ideas about colors and lines and shape.”

With Maine’s storms becoming more intense because of climate change, DiPhilippo knew the shacks could be wiped away with a strong nor’easter or other storm. With that in mind, SMRT Architects and Engineers in Portland in 2022 volunteered to document the last remaining shacks at DiPhilippo’s request. The firm created a set of architectural drawings that can be used to rebuild them now that they are gone.

SMRT took the project a step further by also photographing the interiors of the fishing shacks and creating three-dimensional images so viewers can see what exactly was inside those shacks. The images can be found on the South Portland Historical Society website.

DiPhilippo doesn’t think it would be too costly to build replica shacks (paid for entirely with donated money) and somehow attach them to the rocky ledge where they previously stood so they could better withstand future storms.

She’s heard other people throw out other ideas on social media about the future of Fisherman’s Park, but she feels that replacing the shacks is the answer. The ultimate decision will rest with the South Portland City Council, she said.

For his part, Holt said the shacks could have been saved if a breakwater had been built at the end of Fisherman’s Point decades ago to help divert destructive waves. He also thinks the shacks should look more like working fishermen’s shacks with tarpaper and rough edges, rather than pristine soft yellowish-gray buildings.

“They’re not original,” he said. “They prettied them all up and it’s like make-believe.”

✮

Clarke Canfield is a longtime journalist and author who has written and edited for newspapers, magazines, and the Associated Press. He lives in South Portland with his wife.