Photographs by Paul Cyr

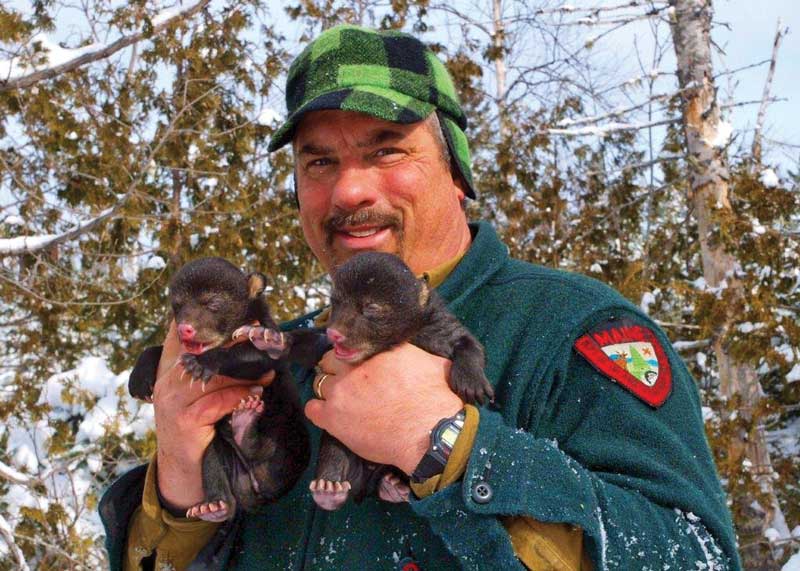

Bear biologist Randy Cross with two newborn bear cubs. Cubs don’t generally open their eyes until four weeks of age.

Bear biologist Randy Cross with two newborn bear cubs. Cubs don’t generally open their eyes until four weeks of age.

Holding what resembles an old-fashioned television antenna high above his head, Randy Cross rotates 360 degrees on his snowshoes. A radio receiver, attached to his waist and connected by a wire to the antenna, emits a steady beep. “We’re near the bear’s den,” he whispers. “We need to spread out and move as quietly as possible.”

It’s February 2010 in a spruce-fir forest 20 miles southeast of Greenville. Cross—chief bear biologist of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife—is leading me and four others through a coniferous forest blanketed by three and a half feet of snow. Several days earlier, Cross reminded me not to wear metal snowshoes or Gore-Tex clothing—both make too much noise. My colleagues and I are dressed in nearly identical Johnson green wool pants and coats.

Randy Cross, chief biologist of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife’s bear research team, weighs a sedated sow bear with help from his crew.

Randy Cross, chief biologist of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife’s bear research team, weighs a sedated sow bear with help from his crew.

Shanna Wilson, a volunteer intern from Unity College, signals the den’s location by waving her arms and pointing in the direction of a nondescript snow mound. It’s her second den discovery in consecutive days. She has a nose for locating bears’ dens. And she has an eye on my vintage 1960s L.L. Bean snowshoes. “My grandfather had snowshoes just like yours,” she whispers in my ear, “if you decide to sell them, please contact me.” After a few moments, I conclude that her innocent remarks are a compliment, not an age insult.

The bear crew lays out a dark gray wool blanket, a new radio collar for the sow, vials for drawing blood, a weight scale attached by rope to a long pole, tranquilizer drugs and syringes, and other biological instruments. “Okay,” Cross says softly, “we’re ready. Time for the mole to do her thing.” The mole is Lindsay Tudor, a state biologist assigned to the bear research crew, nicknamed for her skillful crawling into den holes to gauge the bear’s weight, critical to administering the correct dose of sedatives. Wearing a Petzl headlamp, she re-surfaces a minute later and says, “The sow weighs about 200 pounds and has two newborn cubs.” Cross fills a syringe and attaches it to the end of a five-foot aluminum pole called a jab stick. Inside the syringe is a plunger which, on impact, pushes the drug into a bear’s muscle. Except for the pale-yellow soles of Tudor’s Sorel boots, she disappears in the den with the jab stick and pops back out seconds later. “The tranquillizer works quickly,” she explains to Wilson.

Two minutes later, the drugged sow is dragged from the den and laid on a mesh net and weighed. To keep the cubs warm, Tudor hands one to me and one to Wilson. I place the cub inside my unzipped coat. It starts bawling like a newborn baby, causing Cross to pause from attaching a new radio collar to

the sow. “You’re not holding the cub correctly,” he bluntly admonishes me. “Turn it so its head rests on your shoulder and cuddle it like you would a human baby.” I follow his instructions, and the cub stops crying.

Bear crew researchers replace a defunct radio-collar with a new one on the sow after she’s been weighed

Bear crew researchers replace a defunct radio-collar with a new one on the sow after she’s been weighed

“Sows,” Tudor tells Wilson, “are usually wide awake when I crawl into dens. Their jaws snap in a threatening manner, but they’re mostly bluffing.” During her long career as a mole, she’s crawled into dozens of bear dens and has been bitten only once, seriously enough, though, to require an emergency room visit.

The air temperature hovers around zero—the lower limit of what Cross considers safe conditions for winter black bear work—but inside the bear’s lair, it’s a balmy 32. A month ago, the sow’s twin 8-inch-long cubs weighed 12 ounces at birth and grew quickly, suckling teats on the sow’s sparsely furred underside. Snuggling against her skin, cubs maintain a body temperature of 88 to 98 degrees. Had the sow been unable to store sufficient fat reserves the previous fall, she would have aborted the fetuses.

“Radio collars,” Cross says as he works, “help us better understand and manage bears.” He rattles off important findings: “Some of our radio bears live well into their late 20s. Cubs have a 50 percent chance of reaching their first birthday—starvation being a major cause of death. However, when bears reach age two their survival rate jumps to 90 percent.”

Maine’s black bear study—the oldest, continuous study in the country—has shed light on a previously poorly understood, reclusive forest dweller. Male bears (boars), for example, lead solitary lives except during the summer breeding season. Family groups, comprised of adult females and their offspring, have home ranges of six to ten square miles, compared to an independent male’s 100 square miles. Cubs spend a second winter with their mother, becoming independent in spring when she enters estrus. “As a sow’s independent daughters mature,” Cross says, “they establish their own home ranges, often immediately adjacent to their mother’s. I’ve seen daughters with cubs visiting their mom with her cubs, which would be aunts, uncles, and cousins in our world.”

A sow’s independent sons, though, disperse 100 miles or more prior to establishing their own territories. Onset of hibernation for both sexes, according to Cross, is dictated by food availability. Once every two to three years, when northern Maine’s forests produce a fall bumper crop of beechnuts and beaked hazelnuts, bears postpone hibernation until November or December until most of the nut crop is consumed. These fat-laden nuts provide foraging bears with 20,000 calories a day. In years of food scarcity, bears will den in early October.

By mid-April, four-month-old furry cubs, with wide, dark-blue eyes and oversized paws, emerge from dens, inching forward on unsteady legs to greet a strange new world. In the four months since their birth, each cub will have ballooned from 12 ounces to upwards of six pounds. Their lactating mother, though, sacrifices 33 percent of her weight to aid her cubs’ growth. “Sows with multiple cubs,” Cross adds, “often emerge from their winter den as walking skeletons.’”

Twin cubs are an indication that their mother entered the den with adequate fat reserves. In years of super abundant hard mast (acorns, beechnuts, and beaked hazelnuts), a few sows may occasionally produce triplets.

Twin cubs are an indication that their mother entered the den with adequate fat reserves. In years of super abundant hard mast (acorns, beechnuts, and beaked hazelnuts), a few sows may occasionally produce triplets.

For the next 18 months, sows teach cubs to forage, escape danger by climbing trees, and the art of building a day “nest” in the crown of a tree. In April, when food is scarce, I’ve watched bears forage on flowers at the tops of aspen trees and along streambanks eating skunk cabbages. Twice during May trout fishing trips, I’ve snuck up on sows in the middle of shallow streams, noisily splashing to catch spawning white suckers, which they bite and toss onto the banks for hungry cubs. In June, I’ve marveled at sows teaching cubs how to locate, excavate, and devour snapping turtle eggs buried in warm sandy soils near wetlands.

While Cross’s team is preoccupied collecting biological data on the sow, I borrow Tudor’s headlamp and play mole by sticking my head inside the bears’ tidy 5' by 5' den, which consists mostly of a deep bed of balsam fir needles. It looks like a snow shelter a child might spend hours constructing in a backyard.

After administering a drug to reverse the effects of the sedative, the sow is lowered back into the den and the cubs placed next to her belly. While waiting for the sow to regain consciousness, Cross quietly tells a story of how he once observed two yearlings haphazardly raking leaves and balsam fir branches during construction of their first winter den. “It was poorly built, which annoyed the sow,” Cross said. “She removed all the material and started over as her cubs watched. She first carpeted the den with strips of cedar bark a foot thick, and then added the leaves and fir boughs that her cubs had gathered. It reminded me of how annoyed my mother was after several attempts teaching me how to make my own bed.”

For most of Maine’s wildlife, mortality rates tend to skyrocket in the winter. The opposite, though, is true of black bears. Cross has learned that fewer than one percent of Maine’s 31,000 black bears die in the winter. With large bodies, high body temperatures, and thick pelts, bears are the most efficient hibernators in North America. Hibernation is an evolutionary strategy to survive winter when food and water are in very short supply. To conserve fat reserves from October to April—a period in which bears don’t eat, drink, urinate, or defecate—their metabolic rate drops by 50 percent. By contrast, chipmunks and woodchucks, whose hibernating body temperatures hover around 40 degrees, must awaken every few days to raise their temperatures to 94 degrees. Not so with bears.

As the team worked, the author kept twin winter-born cubs warm by placing them inside his coat until the sow was returned to her den. Photo courtesy the author“Bears live solely on fat reserves for about six months,” Cross says, as we leave the awakening bear and her cubs. “Their cholesterol levels more than double in winter, which would be lethal to us. And yet bears suffer no hardening of the arteries, no formations of gallstones, which, in humans, comes about by an imbalance in the chemical make-up of bile in the gallbladder. A bear’s liver produces a bile fluid called ursodeoxycholic acid, which prevents gallstones.” In China and other Eastern and Southeast Asian countries, according to Cross, “bile bears” are kept in captivity. Their gallbladders are “milked” for bile, which is used in traditional Chinese remedies to successfully dissolve human gallstones.

As the team worked, the author kept twin winter-born cubs warm by placing them inside his coat until the sow was returned to her den. Photo courtesy the author“Bears live solely on fat reserves for about six months,” Cross says, as we leave the awakening bear and her cubs. “Their cholesterol levels more than double in winter, which would be lethal to us. And yet bears suffer no hardening of the arteries, no formations of gallstones, which, in humans, comes about by an imbalance in the chemical make-up of bile in the gallbladder. A bear’s liver produces a bile fluid called ursodeoxycholic acid, which prevents gallstones.” In China and other Eastern and Southeast Asian countries, according to Cross, “bile bears” are kept in captivity. Their gallbladders are “milked” for bile, which is used in traditional Chinese remedies to successfully dissolve human gallstones.

Unlike with humans, though, a buildup of urine does not cause urea poisoning. Instead, hibernating bears convert urea into nitrogen, which is then recycled to build protein. This explains why some hibernating bears emerge after a six-month sleep without losing muscle or bone mass.

In the fading sunlight of late afternoon, we snowshoe back to our vehicles amid the sights and trilling songs of courting white-winged crossbills. The end of a magical day in the Maine woods is about to get better for Wilson when Cross pays her the ultimate compliment: “You pinpointed the last two dens. Keep it up and one day you’ll be a mole on a bear crew.”

Ronald Joseph is a retired Maine wildlife biologist who lives in central Maine. This essay is an excerpt from his memoir Bald Eagles, Bear Cubs, and Hermit Bill, published in 2023 by Islandport Press.