All photos courtesy Helen Scott Morris

A family picnic at “the Gut” on Great Cranberry Island in 1974. Left to right: the author, cousin Gerd Grace, brother Cuyler Morris, cousin Melissa Grace, and cousin Charlie Grace holding a 22 gun that the youngsters used to shoot cans and bottles they found on the beach.

A family picnic at “the Gut” on Great Cranberry Island in 1974. Left to right: the author, cousin Gerd Grace, brother Cuyler Morris, cousin Melissa Grace, and cousin Charlie Grace holding a 22 gun that the youngsters used to shoot cans and bottles they found on the beach.

Picnicking in the Morris family was a century-long tradition that began with my great-grandfather Caspar Wistar Morris. I don’t think he invented the “bacon dog” but he was the first family member to buy a sailboat and begin to explore the outer islands off of Mount Desert Island in the early 1900s.

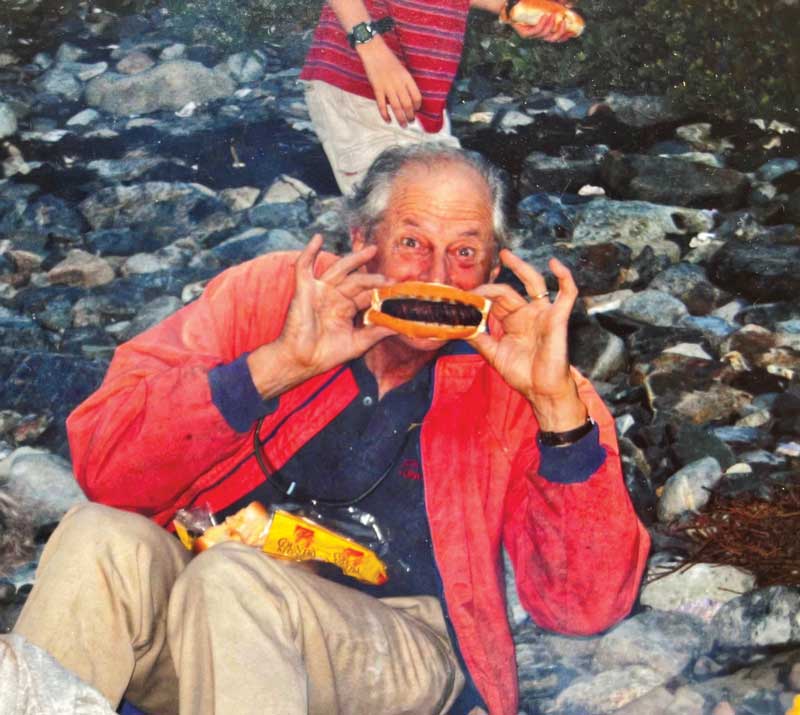

A bacon dog consists of an Oscar Mayer Hot Dog wrapped in Oscar Mayer Bacon cooked over an open driftwood fire. When my father cooked them, the bacon was typically half raw and the hot dog burnt, but slathered with ketchup and mustard in a J.J. Nissen Bun, nothing has ever tasted better.

Bacon dog chef extraordinaire Tom Morris proudly shows off a perfectly burnt and perfectly delicious creation.

Bacon dog chef extraordinaire Tom Morris proudly shows off a perfectly burnt and perfectly delicious creation.

My father was descended from rusticators; his great-grandfather Dr. Caspar Morris and his wife, Laura, built a summer “cottage” in 1888 in Northeast Harbor. Caspar, who was a hiker, not a sailor, built his cottage up against the western slope of Eliot Mountain above the Asticou Inn.

Apparently, he was never taught to swim, so the water represented a hazard. He did, however, give his son Caspar a sailing canoe as a gift when he graduated from college. Caspar (my great-grandfather) later purchased an A Boat.

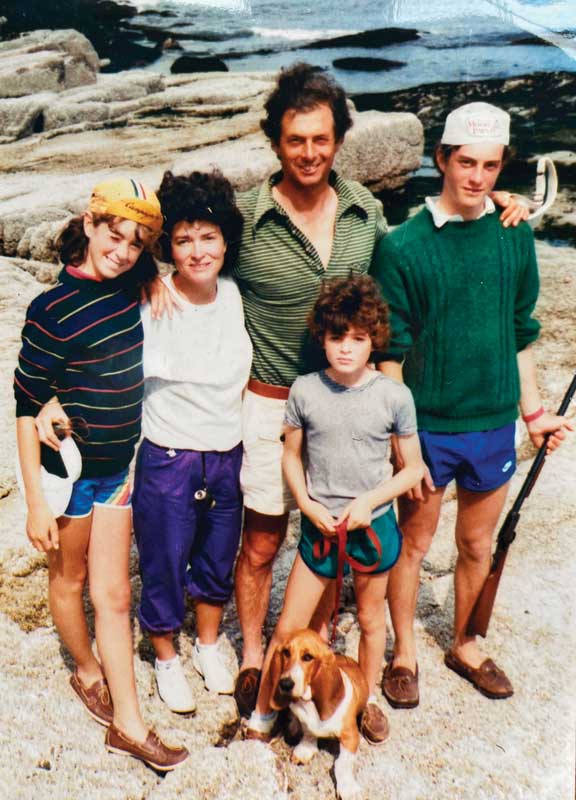

The Dancing Rocks, Baker Island was a favorite picnic destination. This circa 1981 photo shows the Morris family with their bassett hound Marmaduke, who loved bacon dogs.

The Dancing Rocks, Baker Island was a favorite picnic destination. This circa 1981 photo shows the Morris family with their bassett hound Marmaduke, who loved bacon dogs.

My earliest picnic memory stems from a sail on the A Boat when I was four. The occasion was a birthday party for my mother. We sailed out in the old wooden sloop in a southeasterly wind in early October and hunkered down in a narrow cove on the north side of Suttons Island. Because it was a special occasion we shared lobsters, as well as bacon dogs, with dear friends and relatives.

My father may have descended from leisurely rusticators, but he was a hard worker. While building his company, Morris Yachts, he often worked seven days a week. Our family picnics were treasured times.

The A Boat was gifted to the Mystic Seaport Museum in 1975 and our mode of transportation became an old 16' Boston Whaler. The plus was that she was quick. With the Whaler we could go anywhere, anytime. This meant after-work picnics became a thing. We’d meet my father at the Upper Town Dock in Southwest Harbor around five o’clock (although he often ran late). My mother would have packed a picnic in a sturdy rectangular basket with two wooden handles. Anything that didn’t fit in the basket went in a canvas duffel along with warm layers of clothing for after sunset.

If the bay was choppy, we might head straight out to the jutting, cobble point of Suttons Island. If the Western Way wasn’t bearing swells, we might venture farther to Mosquito Cove on Great Cranberry’s western shore, where the sunsets were life-altering. If it was near the solstice, with the days extra long, we might go all the way out to the Gut on the eastern side of Great Cranberry. The Gut is a magnificent place to watch a full moon rise. All of these places are the same ones my father and his siblings explored when they were children. We covered their long-gone tracks with our own.

I loved riding up in the bow, my orange life preserver cinched tight by my father. I would gaze ahead and chew on the salty cotton tie just beneath my chin. Occasionally, my mother would pull me back while she held my sister in her arms. But she could never really keep me back for long, because there was nothing like that salty wind in my hair. Well, nothing except a bacon dog.

Once we anchored and had rowed ashore, the first order of business was gathering firewood. I loved to please my father by heading off briskly down the beach and returning as swiftly as I could with an ample armload stacked up to my nose. Always searching too, for a flat board for my mother to use as a server for Cracker Barrel Cheddar and Saltines.

Once that was done, I would roam the beach, always looking first for a bait bag to hold my treasures—azure blue mussel shells and smooth white clam casings, or a razor clam that I might draw across my bare cheek in mock shaving. If I found a perfect sea urchin, I had won the lottery and would hurry back down the beach to show my mom.

By now the fire would be ready and the bacon dogs wrapped and on the grill. My father would immerse them in the flames, flip the hand-held grill once or twice, and then they would be done. He’d open the black metal grill and we’d peel the hot dogs off with our bare fingers and pop them into a soft bun. I often ate three or more.

Sometimes after supper we would build lean-tos out of blankets, and we ate mountains of marshmallows and made s’mores until my stomach hurt. On one occasion, my brother and I gathered discarded Dixie cups on long wooden sticks and lit them. That was the night the Coast Guard came out to see if we were all right and scolded us for sending such a clear “distress” signal from our prominent point.

On the way home with my sticky face and salt-matted hair, I would watch the phosphorescence cascade off the front of the bow, as if the night stars had fallen into the sea.

Day picnics were a whole other thing and most often happened on Sundays. They were usually large gatherings of our cousins and a myriad of family friends. Multiple boats would be rallied together to get the masses to whatever shore we chose. Baker and Gotts were favorites. Both islands maintain cemeteries holding the bones of hardy souls who once fished and farmed on these outer islands.

Walking across Baker after lunch was always a must. The island rises as you meander up into the daisy flecked field, offering an indelible view back to Mount Desert Island. This view, and a gathering of us on a Morris picnic, would be painted by our friend Tom Schenk, and it hung in the family room of the house I grew up in.

As I passed the cemetery, I could always feel myself going back in time. The lichen crusted split-rail fence offered a gate to enter and pay one’s respects. A tiny wooden house, an original home, still stands amid the rubble of foundations in the tall grasses.

The author’s grandmother and namesake Helen Cuyler Morris with her two children, the author’s grandfather Dewitt Cuyler Morris, and her Great “Aunt Cocky” (also a Helen) on a picnic at Baker’s Island.

The author’s grandmother and namesake Helen Cuyler Morris with her two children, the author’s grandfather Dewitt Cuyler Morris, and her Great “Aunt Cocky” (also a Helen) on a picnic at Baker’s Island.

In the island’s center stands a lighthouse. My Aunt Gerd remembers the lighthouse keeper, who lived on the island with his family, and going up into the tower when she was a child. The lighthouse was automated in 1966, just four years before I was born.

Beyond the lighthouse the woods grow thick, as spruce forests do, and moss frames a winding trail across bared granite, until you hear the surf and the canopy thins as you near the southern shore with its “dancing rocks,” giant slabs laid out as if waiting for dancers. Rusticators, including my great uncle Cappy, once came to Baker Island in their launches, bringing picnics and Victrolas to dance by the sea.

We never danced, but we took off our sneakers and played a dare game of stepping where the surf threatened to crash, occasionally catching a drenching spray that left us shrieking with laughter and cold.

The last picnic we ever took as a family was on Great Gott Island. It was the summer we found out my father had cancer. We did the only thing we all knew how to do with the terminal diagnosis of Stage 4: we packed a picnic basket.

A clear day of promising weather was always a good day to make the journey to Gott’s eastern shore. Here, as always, we could row the dinghy in, touching its bow onto some of the smoothest cobbles of any beach I’ve ever seen. Gott is a great place for “wishing rocks”—stones with a band around the middle. I imagine I looked for many that day.

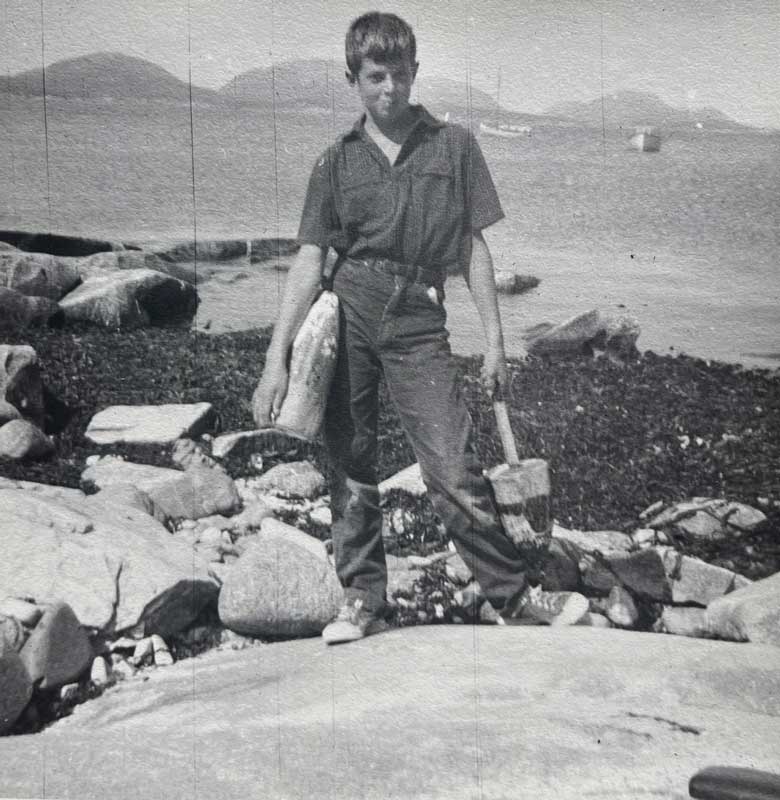

The author’s father Tom Morris in 1952 on the north shore of Baker Island with a treasure trove of buoys.

The author’s father Tom Morris in 1952 on the north shore of Baker Island with a treasure trove of buoys.

We had our picnic in the early afternoon sun. My brother manned the fire that day and roasted the hot dogs.

After lunch we climbed the steep slope into the tunnel of spruce that flanks a path crossing the island. Fairy houses have donned this trail side for many years back, thin shafts of light illuminating them as the sun moves overhead. My parents held hands and crossed through these shafts of light together.

The view when you come out of the woods and into the field on Gott’s western shore is storybook with white clapboard houses, a tiny church, and a cemetery. Over the years we had played speedball in this field, tossed frisbees, and flown kites. My father had carried me on his shoulders, as I now carried my children.

We wandered down the wide mowed path toward the shoreline where masses of beach roses released their scent. Here we were quiet, not so much because of the circumstances of that last picnic, but because this is a place to sit within yourself, to hold memories, to gather the gift of a century of picnics.

Helen Scott Morris lives with her husband in Freedom, Maine. She is primarily a poet.