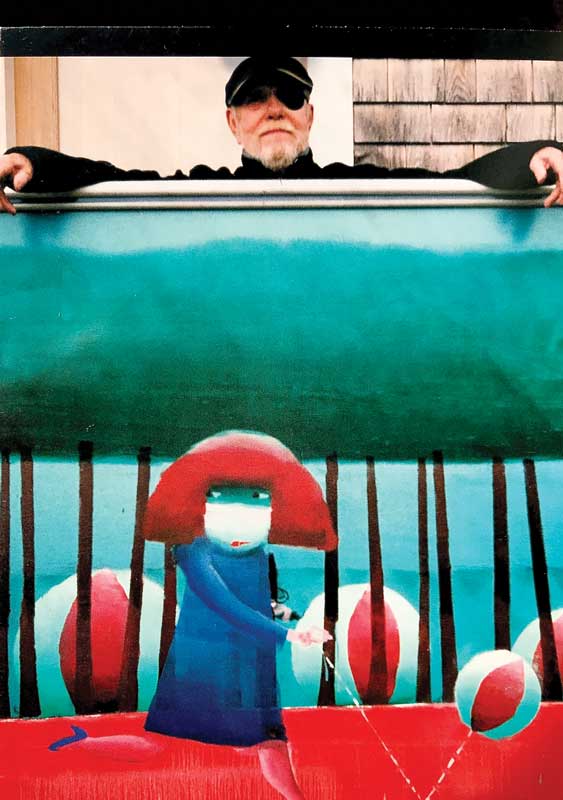

Hamilton with his painting Cap Ferrat 1941, Port Clyde, ca. 2001. Macular degeneration necessitated an eye patch.

Hamilton with his painting Cap Ferrat 1941, Port Clyde, ca. 2001. Macular degeneration necessitated an eye patch.

In Robert Hamilton’s Feeding the Fishes, painted in 2003, the year before he died at age 87 at his home in Port Clyde, Maine, a female figure in red with what appears to be a voluminous afro kneels on the shore handing food to open-mouthed fish from each of her extended hands. The scene appears in a red frame, beyond which is a wall with stenciled decorations.

This enigmatic and theatrical painting, comical with perhaps a wry soupçon of allegory, fits the description of Hamilton’s work given by one of his former students at the Rhode Island School of Design, painter David Estey of Belfast: “impeccable sense of design within humorous, almost-outsider paintings that contain mysterious characters in dreamlike narratives.”

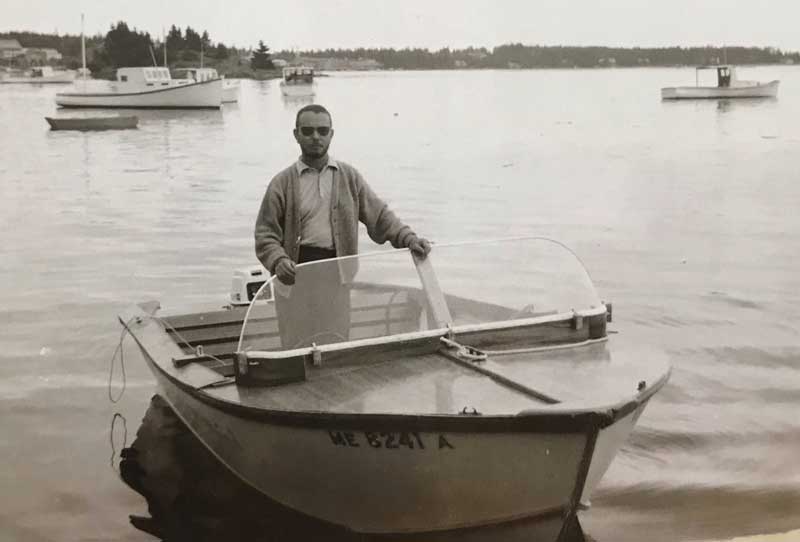

Robert Hamilton in a fiberglass and wood boat that he built, Port Clyde, circa 1968. It was “like a big bathtub, but fun to drive,” according to his daughter.

Robert Hamilton in a fiberglass and wood boat that he built, Port Clyde, circa 1968. It was “like a big bathtub, but fun to drive,” according to his daughter.

Hamilton retired to Port Clyde in 1981 after 34 years teaching at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), where his students included artists Eric Hopkins, Yvonne Jacquette, George Lloyd, and Richard Merkin. He spent the rest of his life painting in Maine. After his death, most of Hamilton’s art remained in storage at his home and studio. In recent years his daughter Victoria Hamilton has worked to have many of the paintings restored, and they have been shown at the Dowling Walsh Gallery in Rockland, Maine.

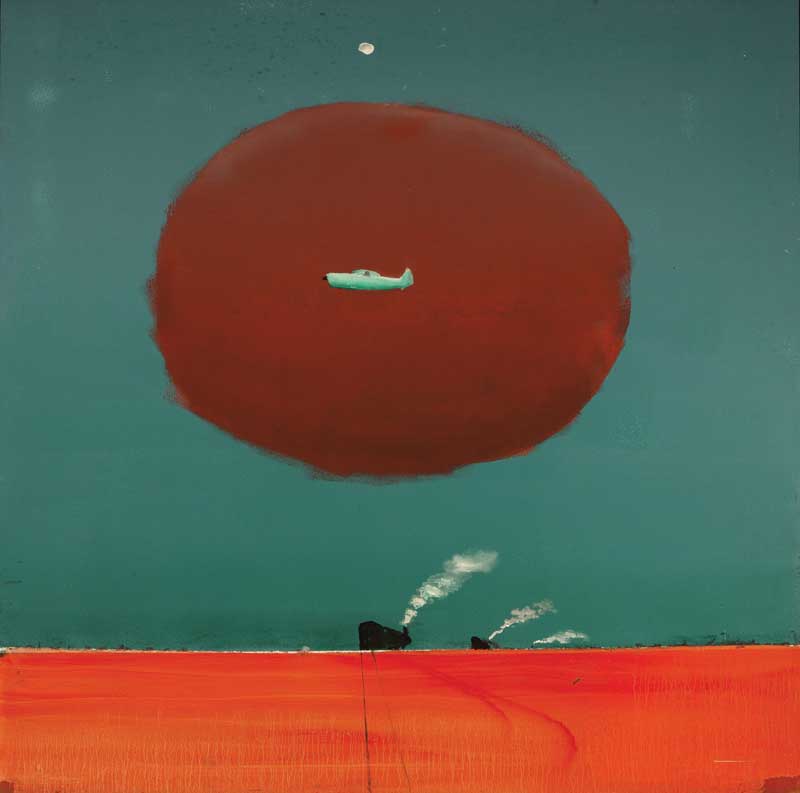

Some of the imagery in Hamilton’s paintings derives from personal experience. As a captain in the Air Force during World War II, he flew 100 combat missions, an experience that earned him a Distinguished Flying Cross, and later led to the appearance of a version of the P-47 Thunderbolt in many of his paintings.

The streamlined fighter often looks toy-like, snub-nosed, zooming along. In Sitting Ducks, 2002, the plane is centered in a large red cloud; below it, a trio of ships—the ducks, one supposes—billow smoke as they sink into the ocean. It’s a freeform intuitive manner of creating canvases that lets mark-making lead to a composition.

“I knew my paintings had to be improvised, spontaneous, made up out of whole cloth, one thing leading to another, accidental, a series of metamorphoses, surprised arrivals,” he wrote.

Hamilton embraced the absurd. Lady Smythe-Tenterhook Hawking Two Marriageable Daughters, 2002, oil on Masonite, 48 by 48 in.

Hamilton embraced the absurd. Lady Smythe-Tenterhook Hawking Two Marriageable Daughters, 2002, oil on Masonite, 48 by 48 in.

Among Hamilton’s favorite props is a red-and-white beach ball, which shows up here and there to lend a note of playfulness to the scene. In the delightfully titled Lady Smythe-Tenterhook Hawking Two Marriageable Daughters, 2002, the large balls stand in for the women in the title, the mother dressed in bright red clutching them under her arms.

In the 2001 documentary Robert Hamilton: Maine Master, interviewer Robert Shetterly and videographer Deb Vendetti let the artist and his art do the talking. Seated, smoking a cigar, wearing a visor and eye patch, he shared pieces of his life-in-art story, from copying Norman Rockwell magazine covers as a young man to studying with John Robinson Frazier at the Rhode Island School of Design (he also spent a year at the Art Students League in NYC).

You can hear Shetterly chuckle now and then as the painter remarks on various topics. In talking about the importance of painters Francis Bacon, Philip Guston, and Max Beckman to his development as a painter, Hamilton notes that their canvases rarely featured jokes whereas his own are full of them. “If a joke comes,” he advises, “cuddle up to it.”

Hamilton also offered two reasons he chose to live in Maine: “It never gets too hot to work” and “You could park anywhere”—perhaps not so true these days.

The film’s soundtrack features Hamilton’s son Scott Hamilton, a professional tenor sax player, covering a number of jazz classics. It’s the perfect accompaniment: the painter loved jazz and sought to emulate the improvisatory nature of the music in his art. He quotes Roy Eldridge, the brilliant trumpeter, as saying that when he played, he imagined he was in a bubble. “I thought that was perfect,” said Hamilton, who was happy to paint outside the limelight.

Hamilton flew 100 combat missions in World War II, which inspired Sitting Ducks, 2002, oil on Masonite, 48 by 48 in.

Hamilton flew 100 combat missions in World War II, which inspired Sitting Ducks, 2002, oil on Masonite, 48 by 48 in.

Port Clyde has been home to a diverse lot of artists over the past century or so. Illustrator and painter N.C. Wyeth may have been one of the first when he began summering there with his family at the cottage called “Eight Bells” in 1920. Over the years, other notable artists lived in and around the village at the southern tip of the St. George peninsula, a group that has included N.C.’s son Andrew, William Thon, Malcolm Morley, Kenneth Noland, Charles Wilder Oakes, and Gary Akers.

Hamilton and his wife Nancy, also an artist, began spending part of the summer in Port Clyde in the early 1950s, renting a place in the woods. In 1958 they bought a small house on Horse Point Road looking out on Muscongus Bay. “We would drive up as soon as school was finished and we’d stay until school started again,” daughter Victoria Hamilton recalled.

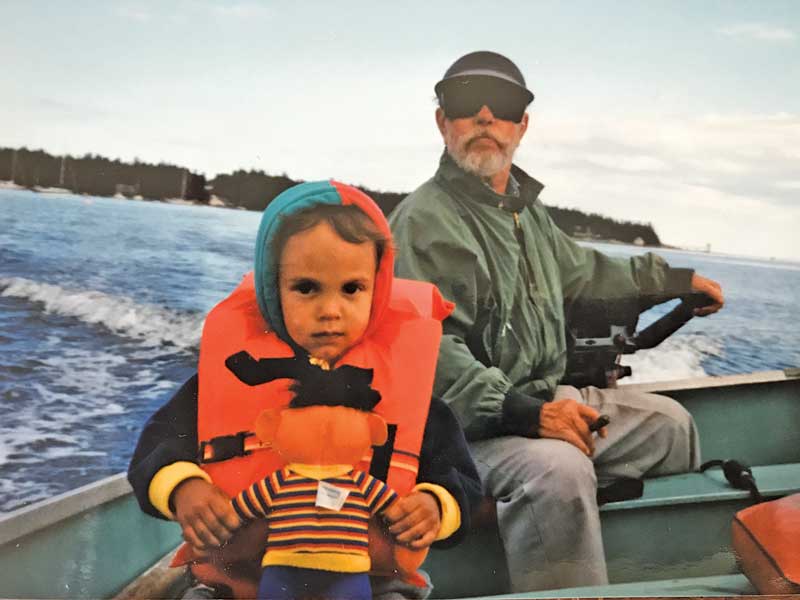

Victoria shared some memories of her father, whose legacy she helps keep alive on Instagram (roberhamilton7475). He loved the open water around Port Clyde and built a fiberglass and wood boat in the late 1960s/early 1970s for excursions. The unnamed vessel was “like a big bathtub but fun to drive,” she wrote. She remembered motoring to Caldwell Island to dig steamers for dinner, “back when you could still do that!” When her father retired the boat in the 1990s, it “sat in the field like a sculpture.”

“If a joke comes,” Hamilton advised, “cuddle up to it.” Lulu’s Haystack, 2002, oil on board, 48 by 48 in.

“If a joke comes,” Hamilton advised, “cuddle up to it.” Lulu’s Haystack, 2002, oil on board, 48 by 48 in.

Victoria followed in her father’s footsteps, attending RISD where she earned a BA in photography in 1979. When her father was still teaching and she was a student, his studio was on Benefit Street in Providence. “I think I visited daily, so I would see him painting but he would stop to talk to me and anyone else who entered.” Jazz was playing all the time, she recalled.

Victoria can’t remember ever asking her father to explain the meaning of one of his paintings. “I knew that my father wanted people to figure it out for themselves.”

Hamilton showed his work at galleries and museums in the 1950s and 1960s, and was artist in residence at the American Academy in Rome in 1974. But later in his career he chose to exhibit his work mostly on his Port Clyde property where, appalled by the venality of the art world, he built a pair of galleries, including an eight-sided venue he called the Octagon. Opening each summer on July 4 with a party and picnic, the museum displayed the artist’s winter work.

In the late 1990s, illustrator Scott Nash and his wife, artist Nancy Gibson-Nash, founders of the Illustration Institute on Peaks Island, paid Hamilton a visit at the suggestion of some of his devotees who insisted he was someone they needed to meet simply because they would “really like him.” Off they went to Port Clyde.

Greeted by Nancy Hamilton, they were ushered into a large barn-board workshop where the painter was stretching a large canvas while a cassette of his son’s music played on the stereo. “Robert walked us across the street and over a field,” they recalled, “to a vast, roughly octagonal shingled building filled with giant, fantastic paintings featuring vivid and crusty cartoon characters performing center stage on the canvases.”

Over gin and tonics, Hamilton explained that the gallery became his studio in the winter. “It’s useless attempting to paint during the summers in Maine,” he said, adding, “Summer’s the time for stretching canvases, showing my work, socializing, and getting recharged.” When Scott compared this work schedule to Aesop’s fable of the ant and the grasshopper, Hamilton replied, “True, but in my story I get to be both!”

Hamilton with grandson Dillon on the youngster’s first boat ride, circa 1994. That’s Hupper Island behind them.

Hamilton with grandson Dillon on the youngster’s first boat ride, circa 1994. That’s Hupper Island behind them.

Hamilton started experiencing vision problems in the late 1990s and was diagnosed with macular degeneration. “One eye was pretty bad,” Victoria noted, and he started wearing a patch in the early 2000s. “I don’t think he could have continued to live if he couldn’t paint so he definitely did not let this slow him down,” she said. Like his fellow Port Clyde painter William Thon, who suffered from the same affliction, Hamilton managed to create some of his best paintings in the last years of his life.

At one point the painter David Estey and his wife Karen drove down to visit Hamilton. They noticed that his neighbor Andrew Wyeth had been there the day before and left a note in the visitors’ log: “Robert, the reason I like your work so much is that it is totally different from mine! Andy.” Totally different, indeed, and completely captivating.

In addition to this magazine, Carl Little writes for The Working Waterfront, Hyperallergic, Ornament, and Maine Arts Journal. He lives on Mount Desert Island.

For More Information

Hamilton’s paintings can be found at Dowling Walsh Gallery in Rockland and Studio 53 in Boothbay Harbor. The Vision & Art Project, which explores “the profound influence vision loss due to macular degeneration has had on both historical and contemporary art and artists,” features a fine bio sketch of the painter on its website.