This close-up of a section of a wooden piling taken from a dock in Belfast Harbor, Maine, shows the massive damage caused by the wood-boring shipworm Teredo navalis. Shipworms are worm-like bivalve mollusks (clams) that use dozens of sharp teeth on their shells to cut through wood fibers as they create burrows in which they spend their lives. The piling shows hundreds of small burrows that were created in only a month or so. Photo by Pamela Eckelbarger

This close-up of a section of a wooden piling taken from a dock in Belfast Harbor, Maine, shows the massive damage caused by the wood-boring shipworm Teredo navalis. Shipworms are worm-like bivalve mollusks (clams) that use dozens of sharp teeth on their shells to cut through wood fibers as they create burrows in which they spend their lives. The piling shows hundreds of small burrows that were created in only a month or so. Photo by Pamela Eckelbarger

At the bottom of the harbor in Newport, Rhode Island, a piece of sailing history is disintegrating. What once were the thick oak planks of a three-masted barquentine are collapsing into wet dust on the sea floor. This is the work of shipworms and the end for what many suspect may be a British naval vessel best known by the name Endeavour.

Shipworms aren’t worms at all but clams. Some 70 species live throughout most of the world’s oceans, from coastal waters to the open sea. The most famous is the naval shipworm, Teredo navalis.

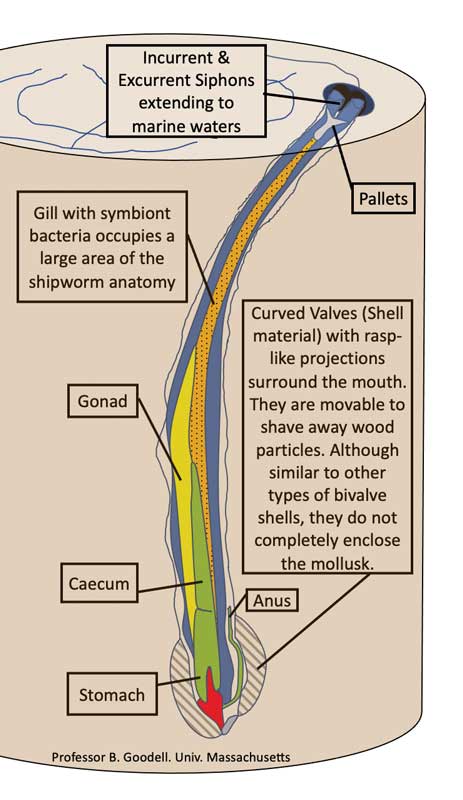

Diagram showing how a shipworm lives in wood. Courtesy Barry Goodell

Diagram showing how a shipworm lives in wood. Courtesy Barry Goodell

Shipworms were a known and present danger by 1768, when Captain James Cook sailed Endeavour westward to watch the Transit of Venus. His observations, when combined with simultaneous observations from different locations around the world, were supposed to help scientists calculate the distance between Earth and the sun. Meanwhile, Cook’s most prestigious passenger, Joseph Banks, was intent on discovering new and exotic plants and animals as Endeavour circumnavigated the southern seas in service of the British Empire.

When they arrived near Tahiti and the fateful night came, “a dusky shade” surrounded Venus, preventing Cook from collecting accurate measurements. It was one of the many occasions when nature obstructed their path. But theirs was not a time of humility. There would be no turning back, especially not because of some celestial shadow, or a tiny marine animal without a backbone. Cook sailed on.

A cross-section of the Belfast dock piling riddled with ship worm holes. Courtesy Barry Goodell

A cross-section of the Belfast dock piling riddled with ship worm holes. Courtesy Barry Goodell

How clams live in trees

When it senses nearby wood, a shipworm larva descends to the surface of the wood and soon begins to dig. Two valves modified into small, curved plates on either side of the shipworm’s head are edged with fine sharp teeth. A pin-sized hole becomes a quarter-inch channel as the animal burrows along the wood grain, excreting a shell-like substance to line the tunnel behind it. Boring rates of three centimeters a week have been recorded in tropical climates, according to Barry Goodell, a professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; he and a colleague in England have been researching how shipworms eat wood. The Latin name Teredo comes from an ancient Greek term for “woodworm.” Teredo can also be translated to “I will grind.” Grind it does, scraping wood fibers, its hair-like cilia moving shavings into its mouth. Its soft, worm-like body extends behind, eventually reaching lengths of six inches or more, ending with a siphon, which the shipworm uses to filter algae from seawater as a dietary supplement. The siphon is also used by females to take in sperm. Fertilized eggs are kept in the gills before being released as larvae—female shipworms can release as many as 100,000 eggs. And so, one shipworm finds another and another and before long there are hundreds inside a single piece of wood, their tiny siphons the only external evidence of their existence. When the labyrinth of tunnels becomes a spongy honeycomb, collapse is imminent.

Up on deck, their eyes trained on the horizon, searching for new worlds of riches and marvels, sailors were often oblivious to the danger lurking below, until it was too late.

Shipworms were well on their way to destroying the wooden hull of this Sparkman & Stephens yacht in Florida before it was hauled and transported to Brooklin Boat Yard for a rebuild. Former BBY owner Steve White said the yard occasionally sees wooden vessels with teredo damage. The marine mollusks destroyed pilings installed at BBY about 20 years ago necessitating their replacement with pressure-treated wood, which has held up much better, White said. Photo courtesy Brooklin Boat Yard

Shipworms were well on their way to destroying the wooden hull of this Sparkman & Stephens yacht in Florida before it was hauled and transported to Brooklin Boat Yard for a rebuild. Former BBY owner Steve White said the yard occasionally sees wooden vessels with teredo damage. The marine mollusks destroyed pilings installed at BBY about 20 years ago necessitating their replacement with pressure-treated wood, which has held up much better, White said. Photo courtesy Brooklin Boat Yard

Preventing the ravages

“As long as man has launched wooden boats or built wooden structures in the sea, he has suffered from the activities of shipworms,” wrote U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Michael Castagna in 1961. For just as long, men have tried to keep the pests at bay. They have coated pilings with arsenic, sulphur, creosote, and concrete. They sealed their boats with beeswax, tallow, and pitch; they sheathed their ships in leather, lead, or copper. They searched in vain for worm-resistant wood. Even today, shipworms cause an estimated $1 billion in damage globally, according to Goodell.

Shipwrights on the Endeavour smeared a layer of tar and matted ox hair between oak floor boards, then hammered broad-headed iron nails into the shallow hull. Once rusted, the nails would create a barrier to the hungry mollusks. It worked, but only temporarily.

In 1770, after missing Venus, terrorizing Maori people, and barely surviving a crash into the Great Barrier Reef, Endeavour was taking on water, fast. Captain Cook hauled out in what is now Jakarta and was horrified at what he saw: shipworms had bored nearly all the way through several floorboards.

“The worms had made their way quite into the timbers, so that it was a matter of surprise to every one who saw her bottom how we had kept her above water, and yet in this condition we had sailed some hundreds of leagues, in as dangerous a navigation as in any part of the world, happy in being ignorant of the continual danger we were in,” he wrote.

Cook did not reflect on why wood-eating animals lived in the sea.

How trees live in clams

“The shipworm is unusual in its relation to its habitat,” wrote Castagna. “Few instances can be cited wherein marine organisms are dependent upon organic products from the land.”

Teredo navalis is but one of hundreds of wood specialists that include other mollusks and also crustaceans. Some live near coastal mangrove forests or the mouths of rivers that drain wooded watersheds. Others drift with floating wood across the open sea. Still others live deep down on the ocean’s floor, waiting for a “wood fall” as saturated remnants of trees finally sink.

All of them have the rare animal ability to break through tough lignin to access sugar, carbon, and other nutrients in wood. How exactly they are able to do this remains elusive to scientists, but symbiotic bacteria and probably fungi are involved in what has been called “one of the finest examples of adaptation within the tree of life.”

Compared to organisms working in rivers or on land, shipworms break down wood relatively rapidly, and are the main degraders of wood in the ocean. In the process, they create habitat and food for other animals, helping to cycle elements between forest and water, land and sea.

So it has been for hundreds of millions of years, long before humans put paddle to water or set sail across the waves.

Much less wood reaches the ocean today—logging removes trees, dams prevent wood from drifting downstream, and cultural preferences keep rivers and beaches “cleaned,” wrote Ellen Wohl in Dead Wood: The Afterlife of Trees.

When we disrupt this exchange, wrote Wohl, “we impoverish the biotic communities and nutrients available in each ecosystem in ways we do not yet fully understand.”

Discovering the connections

Ships added more wood to the sea, picking up and distributing shipworm species around the world, including to new areas where they hadn’t before been a problem. Now, as the global ocean gets warmer, shipworms are finding new habitat in places previously believed to be too cold, such as the Baltic Sea and the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Circle.

In Maine, a 1924 government survey of Penobscot Bay found only Limnoria, wood-boring crustaceans known as gribbles. By the 1950s, naval shipworms were detectable; in 2000, they took less than a year to destroy the white oak piles of Belfast’s new municipal pier.

Shipworms may appear out of nowhere after being absent for long periods of time, according to Kevin J. Eckelbarger, Professor Emeritus of Marine Biology at the University of Maine. This is the case in Maine where shipworm damage was rare for decades until a sudden appearance occurred for several years in the early 2000s, he said. Extensive damage to floats, piers, and pilings occurred throughout the midcoast region for about three years but then slowly disappeared without explanation.

“No one really knows why they come and go without warning, although we do know that shipworm larvae require relatively high levels of dissolved oxygen in seawater so polluted areas usually see few shipworm attacks,” he wrote in an email. “Some shipworm species prefer low salinity, which can occur during periods of unusually heavy rainfall; at those times, larvae attack wood structures until the salinity rises again.”

Shipworms tend to burrow along the grain of wood, but when things get crowded they branch out in all directions, boring at rates as fast as 3 centimeters a week in warm water. Photo by Pamela EckelbargerEckelbarger said in the early 2000s few people involved with marinas in Maine knew about shipworms because they’d never experienced attacks from wood borers.

Shipworms tend to burrow along the grain of wood, but when things get crowded they branch out in all directions, boring at rates as fast as 3 centimeters a week in warm water. Photo by Pamela EckelbargerEckelbarger said in the early 2000s few people involved with marinas in Maine knew about shipworms because they’d never experienced attacks from wood borers.

“I even spoke to a contractor who had just installed some massive docks and pilings around the Portland area using untreated lumber!” he said. “He asked me if this would be a problem because he’d never heard of shipworms and I told him it was a big gamble. However, old lobstermen knew exactly what I was talking about because they used to build their lobster traps from wood many years ago. Present day lobstermen do not.”

Warming temperatures are also altering ocean currents that have historically blocked movement of shipworm larvae into new areas, such as the Polar Front around Antarctica. It was there, just one month after the possible presence of the Endeavour was announced in Rhode Island, that explorers with the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust found the wreck of the Endurance.

Earnest Shackleton and his 27-man crew wanted to be the first to cross the Antarctic continent. Endurance, a barquentine like Endeavour, was designed to resist not shipworms, but ice, with thick layers of pine, oak, and spruce sheathed in greenheart and painted black. In 1915, after 10 months adrift in dense and groaning pack ice, the crew abandoned ship and Endurance succumbed to the pressure, sinking 9,868 feet to the bottom of the Weddell Sea, there to remain.

Wood-eating animals don’t live around treeless Antarctica, and the discoverers found Endurance “in a brilliant state of preservation.”

Meanwhile, back in Rhode Island, the 18th century wooden hull on the ocean bottom lies in barely recognizable fragments. Five hundred years after they grew on Atlantic shores, oak trees finally meet their fate. The shipworms do their work; and the sea absorbs what sun and soil made, and gives it back to the stars.

✮

Catherine Schmitt writes about science for Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park.