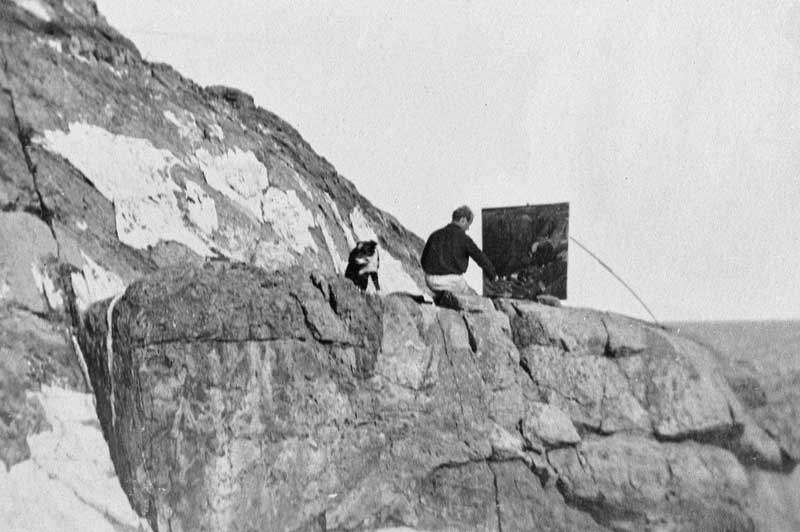

Rockwell Kent painting on Monhegan Island between 1905 and 1910. Image courtesy the Monhegan Museum of Art & History

Rockwell Kent painting on Monhegan Island between 1905 and 1910. Image courtesy the Monhegan Museum of Art & History

Between the 1880s and World War Two, summer art schools introduced the Maine coast to hundreds of aspiring artists who flocked from around the country to picturesque communities such as Ogunquit, Boothbay Harbor, Monhegan Island, and Eastport. These schools began a tradition of the state as an inspiration for artists that continues.

Today, the state is home to two widely respected art schools, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Madison and the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts on Deer Isle. Founded in 1946 and 1950, respectively, these schools celebrate and promote Maine’s role as an art mecca.

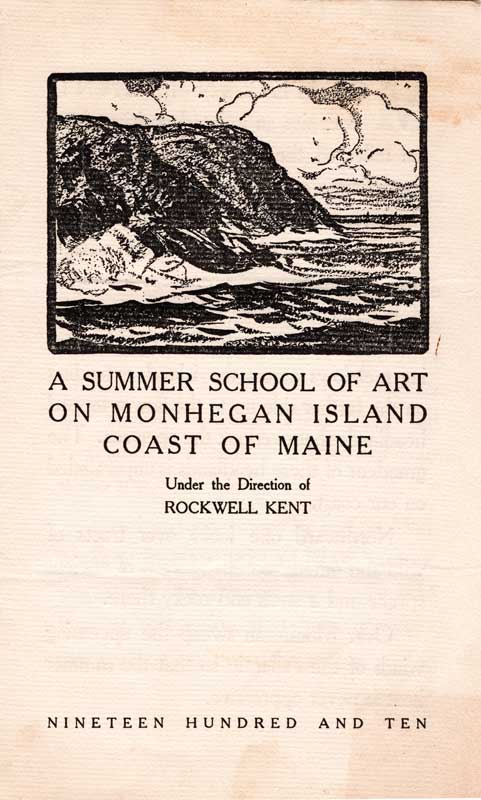

Prospectus for the Summer School of Art directed by Rockwell Kent on Monhegan Island in 1910.Image courtesy the Monhegan Museum of Art & HistoryMaine’s first known summer art school was organized by N.H. Carpenter, the secretary of the Art Institute of Chicago. In March 1889, Carpenter issued a circular announcing “July on the Sea Shore,” which described a four-week course of art classes on Cushing’s Island in Casco Bay. Participants traveled by train from Chicago to Portland and stayed at the island’s new Ottawa House Hotel. For the month of July 1889, students received instruction from Chicago marine and landscape painter George H. Gay, who was assisted by artists Alice Hay, Lydia Hess, A.T. Van Laer, Jennie Wright, and Fannie Bond. Classes were held daily from 9 a.m. to noon and from 2 to 5 p.m.

Prospectus for the Summer School of Art directed by Rockwell Kent on Monhegan Island in 1910.Image courtesy the Monhegan Museum of Art & HistoryMaine’s first known summer art school was organized by N.H. Carpenter, the secretary of the Art Institute of Chicago. In March 1889, Carpenter issued a circular announcing “July on the Sea Shore,” which described a four-week course of art classes on Cushing’s Island in Casco Bay. Participants traveled by train from Chicago to Portland and stayed at the island’s new Ottawa House Hotel. For the month of July 1889, students received instruction from Chicago marine and landscape painter George H. Gay, who was assisted by artists Alice Hay, Lydia Hess, A.T. Van Laer, Jennie Wright, and Fannie Bond. Classes were held daily from 9 a.m. to noon and from 2 to 5 p.m.

While the Chicagoans did not return after their month on Cushing’s Island, Maine’s next summer art school was of a much greater duration. In 1898, Boston artist Charles Woodbury, a seasonal visitor to Ogunquit, settled there year-round with his wife and son. That summer, he offered a six-week course in drawing and painting in pencil, watercolors, and oils. Woodbury gave two lessons a week, followed by a Saturday critique. As Ogunquit developed into an art colony in the early 20th century, the popularity of the school grew with it, attracting between 75 and 100 students each season. Woodbury taught his summer course from 1898 to 1917 and again from 1923 to 1939. According to the book Ogunquit, Maine’s Art Colony, the artist was “a charismatic, quiet teacher who offered his art students a traditional art course but encouraged their individuality.”

Boothbay Harbor became the site of Maine’s next summer art school. Known as the Commonwealth Art Colony, this school was founded in 1906 by artist Asa Grant Randall, a Waterboro native, who taught manual arts in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, and Providence, Rhode Island. Courses included drawing and painting from nature, commercial design, jewelry making, and manual arts. Boothbay Harbor was promoted as an ideal location for summer learning. The Colony’s 1915 brochure described the town as rich in subject matter noting that:

The Commonwealth Art Colony’s Morris Hall housed an assembly hall, a recreation room, studios, and bedrooms. Image courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission

The Commonwealth Art Colony’s Morris Hall housed an assembly hall, a recreation room, studios, and bedrooms. Image courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission

“Artists, Art Students and Photographers will find an unlimited number of subjects such as bridges, wharfs, and ships; cliffs and rocky shorelines; islands and harbor views; storm-swept cedars, spruces, and rows of great willows; fish houses and vine-covered homesteads; winding roads and forest paths; and the people themselves busy at their daily labor.”

Asa Randall directed the Commonwealth Art Colony through the summer of 1930. The colony’s demise can be attributed in part to the loss of its dining hall, which burned in 1921, and to competition from the Boothbay Studios, another local summer art school run by Frank L. Allen from 1921 to 1942. Allen was a well-known painter, graphic artist, writer, and lecturer. His teaching positions included director of education at the noted Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan.

Just up the coast from Boothbay Harbor, artist Rockwell Kent conducted an art school on Monhegan Island during the summer of 1910. Based in New York, Kent spent much of his time between 1905 and 1910 painting on this remote island as well as designing and constructing cottages there for himself, his mother Sarah Kent, and their friend Mary Kelsey. In March 1910, he announced “A Summer School of Art on Monhegan Island, Coast of Maine.” According to Kent biographer David Traxel, “Rockwell’s mother offered to pay for materials to build the school’s studio if he did the work. He left for Monhegan in May, immediately set to work, and by mid-June, just as the students arrived, he had finished.”

Describing Monhegan as an isolated place of strikingly varied character, Rockwell Kent’s prospectus for the school attracted between 15 and 20 students for the four months between June and September. According to Kent’s 1955 autobiography It’s Me O Lord, he and Julius Golz, a former classmate at the Henri School in New York, taught “people reckless enough to pay ten dollars a month to study with two young fellows who were entirely reckless in proclaiming that they had any ability whatsoever to teach.”

While Rockwell Kent’s summer school lasted for only a season, the studio he designed and built to house it remains a landmark on Monhegan. Subsequently used by artists Alice Kent Stoddard and James Fitzgerald, the building has been owned since 2003 by the Monhegan Museum of Art and History, which opens it to the public during the summer.

Painter Charles Woodbury teaching a class at Ogunquit in the 1930s. Image courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Painter Charles Woodbury teaching a class at Ogunquit in the 1930s. Image courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission

A second summer art school was introduced to Ogunquit in 1911 by Hamilton Easter Field. A New York artist and art critic who first visited the southern Maine coast in 1902, Field called his school the Summer School of Graphic Arts. From 1911 until his death in 1922, he taught painting and life drawing, and his fellow artist Robert Laurent offered classes in sculpture and wood carving. While Ogunquit’s well-established Charles Woodbury continued to provide instruction in painting post-Impressionist seascapes and landscapes, Field advocated for the more experimental approach of European modernism.

In the summer of 1922, the New York painter George Pearse Ennis taught a small class of art students in Eastport. Five years later, Ennis returned to establish the Eastport Summer School of Art in affiliation with the Grand Central School of Art in New York, of which he was a faculty member. The summer school’s 1927 catalogue characterized Eastport as “a fresh country, rich in materials of the most varied sort.” Ennis and fellow artist Edward Greacen gave a six-week course in outdoor watercolor and oil painting and provided criticisms to their students. Some classes were held in the former Boynton High School, which the City of Eastport refurbished for the art school.

An art class at the Eastport Summer School of Art about 1930. Image courtesy the Tides Institute

An art class at the Eastport Summer School of Art about 1930. Image courtesy the Tides Institute

From 1931 to 1936, the Eastport Summer School of Art operated on its own. During this period, Ennis’s leadership continued to attract many students as well as talented faculty members such as lithographer Stow Wengenwroth. Following the 1936 season, Ennis was killed in an automobile accident, thus ending the school. His death at the age of 52 was eulogized by the Eastport Sentinel in the following words: “The value to Eastport of his presence and the school was nothing less than tremendous, not only in the publicity it produced but for the distinguished group of artists and tourists it attracted.”

The Sentinel could have been speaking for Kent, Woodbury, and Maine’s other art school founders. As George Pearse Ennis said, “art springs into being only amid surroundings that kindle with their beauty, that awe with their grandeur, that disturb deeply with their mystery.”

✮

A native of Portland, Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr. directed the Maine Historic Preservation Commission from 1976 to 2015 and has served as Maine State Historian since 2004.