Weather hints and lobster buoys

I enjoyed Peter Spectre’s recent Sailor’s Medley column “On the Weather” and have some comments to add.

I have read that before radar and GPS, ferry captains heading for the Fox Islands would sound their horns not only to warn other boats but also to determine the location of navigation buoys and land by listening to the reflected echoes.

For sailors and others out at sea who are struck by severe low-pressure storms, you should sail on starboard tack or have the wind on your starboard side even if the direction is not precisely where you want to go. By doing so, you will sail clockwise around the path of the counterclockwise winds; whereas if you sail on port tack in a direction seemingly headed more directly to your course, you will sail toward the center of the storm. I learned this long ago in a race from Newport to Bermuda, in which a fierce storm hit us after crossing the Gulf Stream.

As for the writer in Letters to the Editor who is concerned about those lobster buoys: The best way to avoid them is to observe the direction of the tidal current or wind. This is easy to do if they have toggles. Steer past them on the side where the tide or wind will keep you away from them instead of carrying you toward them. If your props get entangled, you are in serious trouble, but there is one possibility which could help. The line leading down to the traps can be hauled in far enough and secured so that it leaves enough slack in the upper part of the line to loosen the strain where it is wrapped on your propeller. This in turn will sometimes allow you to unwrap the line enough to free the pot buoy using a boat hook or other device. Never cut the line leading to the traps without an attached buoy! In the worst case you can take hold of the buoy with the loosened line, cut it free, and securely tie it back to the line which connects to the traps.

Peter Parsons, Via email

Those pesky lobster pots

I have spent almost 60 years sailing on the coast of Maine, and the number of lobster pots has increased in that time. I no longer consider running inshore at night because of the risk of snagging a pot. But we have learned a few things about pot avoidance in those years, and we do snag them less frequently.

There are, of course, mechanical solutions. Baskets around the propeller, spurs on the shaft, and fairing strips to prevent a pot warp from snagging between the hull and rudder. Here are two lessons we’ve learned. Maintain vigilance at all times. Assign someone in the crew to spot pot buoys and talk the skipper through the maze. Even on a powerboat with a flying bridge, momentary inattention in adjusting the auto pilot or checking the chart plotter can lead to a snag. On sailboats with dodgers, jibs and other impediments to a 180-degree view ahead, the risks are even higher. A second set of eyes on the water provides insurance that a pot will not be missed—even when heading into a low sun, when pots are particularly hard to spot.

Know the direction in which the current is flowing, and factor that into your decisions. The greatest danger for most cruising boats, power or sail, is running between the pot and the toggle, a float five to twenty or more feet down the warp towards the pot. If you are unsure if a pot has a toggle, or the toggle might be towing under, steer down current of the marker that you can see. This should prevent you from running over a partially submerged line between the toggle and the pot.

Rich Feeley

Concord, MA

Just slow down

I offer a gentle suggestion to the letter writer from Maryland seeking advice on how to avoid lobster pots and the resultant prop wrap: SLOW DOWN. Seriously, please, just slow down. It seems like it must be easy to forget when planing along that every pot is directly tied to a hardworking man or woman’s livelihood. And every line cut (or sheared by the blasted shaft razors so popular now) means a loss of gear and income. We need to all share these beautiful waters. But your recreational time in “Vacationland,” shouldn’t come at the cost of a working Mainer’s livelihood.

Ron Letourneau

South Portland, ME

The yacht Windseye

I’m a recent transplant to Vienna, Maine. A friend gifted me a copy of your March/April issue.

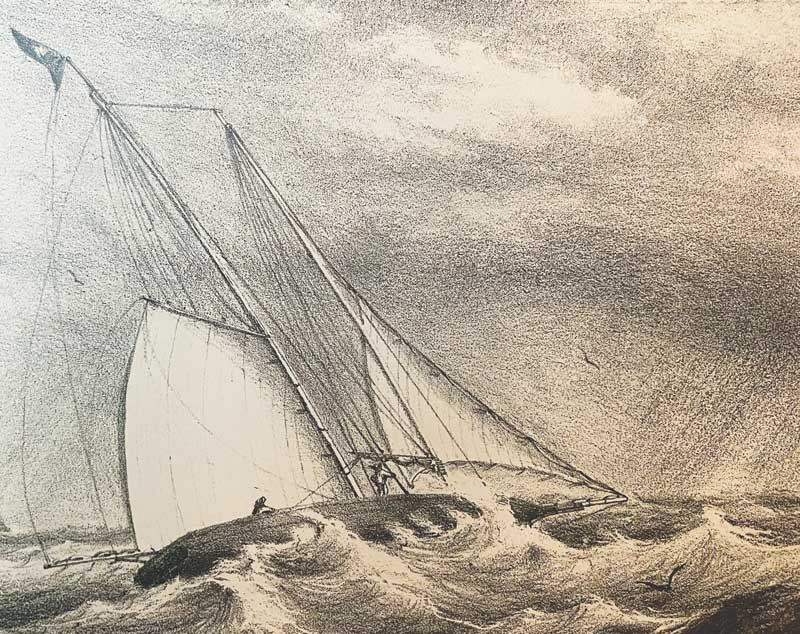

On page 16 is a sketch of a schooner beating to windward. Something struck a chord with me. I knew I’d seen it. It is Windseye. In 2011 my father published a book of sketches drawn by his great grand uncle Dr. Charles Ellery Steadman. He was a surgeon, an artist and a draftsman—some of his medical sketches are preserved by the Dorchester Medical Society. He also made a series of sketches of his yacht Windseye, which were originally published in Boston in 1857 in the book Mr. Hardy Lee, His Yacht. Dr. Steadman’s sketches were drawn in pencil. But he had them printed as lithographs. Someone had to carve them into stone. A young artist was hired to do it. In 1974 an art historian attributed the stone carvings to Winslow Homer.

Dr. Steadman was a shipboard surgeon during the Civil War. He was stationed aboard the USN steam schooner Huron in the Blockade of Charleston. He was there in February 1864 when CSS Hunley torpedoed and sank USS Housatonic—the first time a submarine sank a ship in war.

Tom Hale, Via email

You have sharp eyes. That is indeed Windseye, reprinted from the 1857 edition of Mr. Hardy Lee, His Yacht.

—The Editor

✮