Photos by Herb Swanson

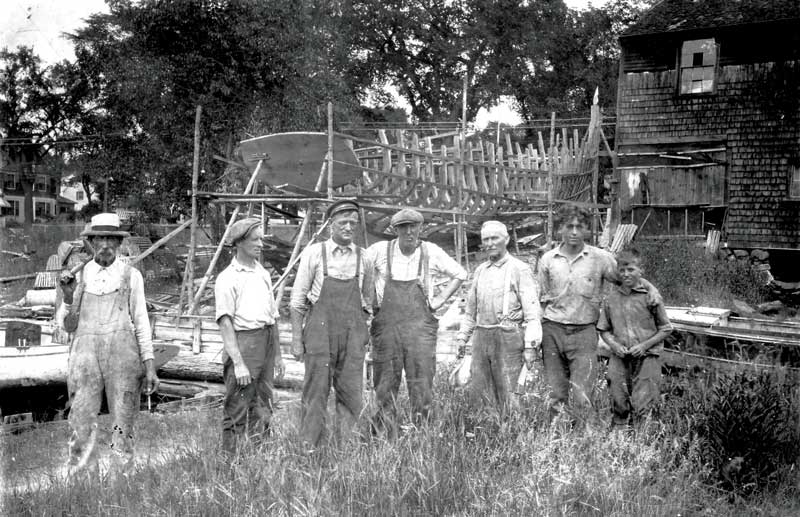

From left to right: William Warner (father of Bernard), Bernard Warner, Wainwright Chick, Fred White, Lem Brooks, Lionel Amerault, and Albert Welch, photographed in August 1924 at Bernard Warner’s boatyard. Behind them, under construction, is the Mimme V., built for the Hathaway Machinery Co. in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy Rich Woodman

From left to right: William Warner (father of Bernard), Bernard Warner, Wainwright Chick, Fred White, Lem Brooks, Lionel Amerault, and Albert Welch, photographed in August 1924 at Bernard Warner’s boatyard. Behind them, under construction, is the Mimme V., built for the Hathaway Machinery Co. in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy Rich Woodman

Just about every morning during sailing season, Rich Woodman wakes up with the birds, pours himself a mug of strong coffee, and checks the weather forecast. If he likes what he sees, he climbs into his truck and drives a mile or so from his riverfront home to the Eleanor, an elegant 55-foot gaff-rigged schooner docked at Kennebunkport’s historic Arundel Wharf. From there, two or three times a day, he’ll ferry passengers down the Kennebunk River, into the Atlantic Ocean, and back, pointing out historic sites and wildlife along the way. Woodman and a crew of local craftsmen built the schooner in 1999 along the lines of Herreshoff’s 1935 Mobjack design. With spruce spars, a mahogany transom, and locust rails, schooner Eleanor can take up to 17 passengers on a leisurely two-hour sail, often cruising past the 1905 nine-bedroom shingle-style landmark that became the oceanside retreat of a political dynasty.

Woodman and a crew built the schooner Eleanor, which operates as a daysailer out of Kennebunkport.

Woodman and a crew built the schooner Eleanor, which operates as a daysailer out of Kennebunkport.

Around the time George Herbert Walker Bush’s family was building that summer compound on Walker’s Point, Woodman’s maternal grandfather, Bernie Warner, was launching his maritime business. A century ago, just a stone’s throw from Eleanor’s berth, Warner built fishing vessels, schooners, and even a tugboat for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Born on Prince Edward Island, Warner grew up in Kennebunkport, where his father worked in shipyards on the river. After apprenticing with canoe maker George Chick, Warner set up shop for himself in 1910. In his heyday, he kept 28 men busy all winter, making him the largest employer in town.

By 1929, Kennebunkport’s Turn O’ The Tide reported, Warner’s boats were selling for $20,000 to $30,000 each. Business was thriving.

“We launch the boats all equipped right here,” Warner told the paper. “Last September there were three or four thousand people here to watch the launching. We do it right, with all the fixin’s.”

Woodman especially admires his grandfather’s round stern boats. “Not easy to build,” he noted. “Fisherman liked them because their nets wouldn’t get hung up in hard corners. These were his own designs, yet he was also old school. He’d construct a half model—the only plan for the boat.”

Warner died in 1958, a year before Woodman was born. Luckily, Woodman’s mother, for whom his schooner is named, held onto vintage photos documenting her father’s enterprise. Eleanor Warner Woodman died in 1991, but her son still keeps those sepia snapshots in a shoebox, and displays other nautical photos and memorabilia in the boatshop he built a few miles from his home and on the wall of the rustic dockside office/museum where the Eleanor’s passengers check in.

When Woodman restored this Elco, he used modern materials and techniques to make it look original while bringing it operationally into the 21st century.

When Woodman restored this Elco, he used modern materials and techniques to make it look original while bringing it operationally into the 21st century.

The Kennebunkport Historical Society is also keeping the Warner legacy alive. In her July 9, 2020 “Throwback Thursday” column on the society’s website, archivist Sharon Cummins writes about the last chapter in his long career: “After launching the Gloucester on August 23, 1941, Bernie closed up shop and briefly went to work at the South Portland Shipyard. In 1944, Arthur Ricker leased Bernie’s old yard from the new owner Lewis Burr and put Bernie Warner back in charge. The schooner Carolyn and Priscilla was launched July 4, 1945, and a 33-foot fishing vessel for Freemont Ridlon of Cape Porpoise named Bumble Bee was built in 1946.”

Among Warner’s most long-lasting craft is the Phyllis A, a 58-foot gill-netting fishing vessel built in 1925. Nearly 75 years later, Woodman discovered it, to his great surprise, in Massachusetts.

“We were just about to start work on the Eleanor, and a fellow down in Gloucester had a schooner, newly built,” Woodman recalled. “He’d done a really nice job, and I wanted to see what I could glean from him. So we took the truck down there, and we spotted this old wooden fishing boat, which had just gone back into the water.”

“That looks like one your grandfather built,” said Woodman’s wife, Kris. He’d shown her pictures.

“So I started talking to this old guy, who told me the boat had, in fact, been built in Maine by Bernie Warner. He even remembered the day his dad picked her up.”

The “old guy” Woodman chatted up happened to be Alvin Arnold, who, along with his two living brothers and sister, wanted to preserve the vessel as a teaching tool for future generations. With more than a little help from friends, including Arundel Wharf owner Bob Williamson and the Kennebunkport Historical Society, Woodman acquired the boat and helped start the Phyllis A. Maritime Heritage Association, raising money for repairs and bringing her, for a time, to Maine, before returning the vessel to her present home in Gloucester.

It was the last thing Woodman expected, randomly stumbling on a still-seaworthy Warner-built fishing vessel. But then, he’s no stranger to serendipity.

“Growing up, I lived with my parents and two brothers in Wellesley, Massachusetts, but we spent summers in Kennebunkport. One day, a buddy of mine showed me his Hobie Cat. I bought it and sort of taught myself to sail, along the beaches” he said.

In 1980, a fleet of square-rigged Tall Ships arrived in Boston to mark the city’s 350th birthday, and Woodman went with a friend to see them. He was captivated, and couldn’t believe his luck when he became one of 35 young Americans invited to apprentice on the crew of a Norwegian sail training ship, the Sorlandet.

“We had to learn all 300 lines of the boat, and I had to climb the rigging about 110 feet off the deck. All of a sudden I think, this is fun. We raced with the fleet of Tall Ships from Denmark to Amsterdam. That really opened my eyes to sailing,” he said.

Rich Woodman cruises up the Kennebunk River in the electric boat he designed and built in 2001. Adapted from an early 1900s Charles Mower sailing dory design, it’s powered by a 36-volt electric trolling motor and also rigged to sail.

Rich Woodman cruises up the Kennebunk River in the electric boat he designed and built in 2001. Adapted from an early 1900s Charles Mower sailing dory design, it’s powered by a 36-volt electric trolling motor and also rigged to sail.

After graduating from the University of New Hampshire, Woodman went back to sea, this time crewing on the Rockland-based windjammer, Nathaniel Bowditch. And he enrolled in Kennebunkport’s Landing Boat School (now called The Landing School). After completing the year-long program there, he landed a plum boatbuilding job at Mystic Seaport, but was once again diverted into sailing, this time on the schooner Rachel B Jackson.

“My route was never planned. I just jumped on opportunities as they came along,” he said.

After a season on the schooner, and another Tall Ship race, Woodman was offered a job building boats in Camden, Maine, at Cannell’s. It was a big step forward.

“I had read about Cannell’s shop in WoodenBoat Magazine, and they did beautiful work.”

Next came an invitation to teach at The Landing School. With students, he restored the Lazy Jack, a 36-foot scaled down topsail schooner modeled on 19th-century Gloucester fishing boats, which he used to start a charter sailing business. Another classroom project was a replica of a 1926 Hacker Craft. His dual career course, sailing and boatbuilding, was charted.

Like his grandfather, Woodman is not afraid to experiment with designs, materials, and techniques. As a builder and restorer, he respects tradition, but he’s not enslaved by it.

In fact, he was ahead of the curve with the small, affordable electric boat he designed and built in 2001. His latest restoration was a sleek launch built in 1916 by the Elco company, a turn-of-the-century pioneer of battery-powered vessels.

“This boat was as advanced as the automobile of its time,” Woodman said.

The Elco’s owner considered electrification but opted for a gasoline engine. Rather than restoring the boat as built, Woodman used a variety of techniques and modern materials to make it look original while bringing it operationally into the 21st century. “The hope is that it will be around another hundred years,” he said.

Next in line: a 1922 Chris-Craft, which needs, at the very least, a new bottom and deck planking.

For Rich Woodman, maritime history isn’t just something you read or talk about. It’s something you do. Lately, one of his two sons has been doing it, too. At the back of the shop, 17-year-old Sam Woodman is restoring a 1958 14-foot lapstrake runabout, built in Orono, Maine, by the White Canoe Company. On a nearby wall, in orderly rows, hang some of Bernie Warner’s time-tested tools—adzes, planes, bevel gauges.

A beautiful, durable legacy, still as useful as ever.

Charlotte Albright is a freelance writer, editor, and podcast producer who lives in Vermont but gets back to Maine, where she was once a public radio host and reporter, every chance she gets.